ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Calling, Conflict and Consecration: The Testament of Ida Scudder of Vellore

Reena Mary Georgea

Abstract

How does the hand of God grasp a hesitant human hand to reach out to a world that needs health and wholeness?

This article describes how one night, a young Ida Scudder experienced a painful and life changing encounter with God. Through her first person account and her personal parable, it traces the conflict, surrender, fruitfulness and breaking points that followed - on a journey that led from a one-room dispensary to the Christian Medical College, Vellore.

For those who feel prompted to serve in health care, it is a testimony of the power of a vocational call, and the provision of God in the face of human inadequacy.

Introduction

Some of the foundational initiatives in Christian health care had their origins not in a policy decision but in a vocational call and an act of obedience. Among the pioneers who came to India were John Scudder, the world’s first Protestant medical missionary, Clara Swain, the first woman medical missionary, and Mary Glowrey, the world’s first physician-nun and the founder of the Catholic Health Association of India. All three were already qualified physicians, and for all three, the call to missionary work came through a written text. John Scudder was moved by a pamphlet about millions who had not heard the gospel.1 Clara Swain came in response to a letter about the health needs of women in the Indian zenanas.2 Mary Glowrey, a practicing doctor in Melbourne, read a brochure about work being done in India and became a nun in order to go out as a missionary.3

The call of Ida Scudder of Vellore (Fig.1), however, came to a young woman who had resolved never to be a missionary or a doctor. An encounter compelled her to make a life changing decision overnight. She lived out that commitment for the next seventy years of her life. The immediacy of Ida’s encounter has some parallels to the calls in Christian history of Abraham, Moses, Saul of Tarsus, and Francis of Assisi.4 (Genesis12:1, Exodus 3:1-14, Acts 9:1-15). They met God in unusual circumstances, were overcome by fear and awe, but surrendered, obeyed, and were empowered to lead movements that had a lasting impact.

Ida Scudder’s call also bears studying because there are first person accounts, spoken and written, describing the events that happened.5,6 Contemporaneous biographers and colleagues have narrated the story of her life and work.6,7 Not published, however, is ”The Monk’s Story,”8 handwritten by Ida Scudder and accessed recently amongst her papers. This is Ida’s own parable about the meaning and impact of her encounter with God.

I have juxtaposed, below, Ida’s description of the events of her call and “The Monk’s Story,” the allegory of the spiritual struggle within.8 They are presented here not as an academic analysis but as steps in the unfolding of a vocation for those who might wonder:

Does God still encounter people today?

Can God work with human resistance and weakness?

Is it possible for the nature of a call to change?

The Formation

In 1870, the year Ida Scudder was born, Clara Swain, the world’s first woman medical missionary arrived In Bareilly, India. Many were skeptical:

…the native women in India are quite shrewd enough to pin their faith to the colours of the male doctors, native or European. Excepting a few strong-minded European ladies in Madras, and perhaps in Bombay, there is not the faintest demand for female doctors… If these good and wise ladies would turn their attention to missionary enterprise, they might prove useful. But in medicine, their efforts can only result, as has been the case here, in the production of an inferior article for which there is literally no necessity or demand in India.9

Ida was born into a family where many of the men were doctors. Her grandfather, John Scudder, and his sons had founded the American Arcot Mission west of Madras in South India.10 They worked as evangelists and itinerant surgeons setting up churches, schools, seminaries, orphanages, and a few dispensaries. Despite the early deaths of spouses and children, the work of the mission grew.

John Scudder’s son, Silas Scudder, left his medical practice In America to begin the mission’s first hospital in Ranipet, the town of Ida’s birth. It was the only hospital in the region. Administrative and clinical pressures and ill health led to Silas’s death at the age of 44. The next doctor who took charge of the hospital died, a short while later, of hydrophobia (rabies).10 Ida’s parents continued working in India. At the age of six, Ida witnessed the ravages of a famine that left three million dead. Images of dead bodies on the road and of handing out rationed food to emaciated children remained in her memory when her family went on furlough to America. Ida was resentful that despite what they had endured, her parents chose to return to their work in South India.7,10

The rebellious teenager was offered a place in Northfield Seminary, a private secondary school founded by the evangelist, Dwight L Moody, in Massachusetts.11 Happy years spent with close friends on a beautiful campus on the banks of the Connecticut River confirmed Ida’s conviction that America was where she belonged. She stated that she would never become a missionary or work in India. After Northfield, she planned to enter Wellesley College.6,7 The contrast between the poverty and suffering Ida had witnessed as a child in India, and the green, prosperous America of her student years is described at the beginning of ‘The Monk’s Story.’

There is a beautiful story told of a young monk. He was placed in a village at the foot of a beautiful mountain, to work. Before he had been there very long he found the village was full of sickness and sorrow, sadness and death. After working there for some months the monk felt he could no longer endure it. He therefore packed his belongings and moved up to the top of the mountain with its cool sweet air. The monk daily read his Bible and prayed and communed with God. All about him was perfect peace and joy.8

Unexpectedly, in 1890, Ida was called to India for a short while to help her ailing mother. Determined to return, Ida sailed for India and joined her parents on the mission compound in Tindivanam, South India.7 It was there one night she received a call.

The Call

Suddenly in his trance the monk saw a figure coming up his garden path. And as he looked he said in an awed voice, ‘“It is the Lord. My Master. “He prostrated himself at His feet. ‘Yes,’ said the Master, ‘It is I. I have come for you. I have need of Thee. I want you to return to the village you have left and go back and work for them.8

In Ida’s words, one night in the Mission Bungalow:6

As I sat alone at my desk in my room in the little bungalow, I heard steps coming up to the verandah and looking up I saw a very tall and fine-looking Brahmin gentleman. I asked him what I could do for him, and he said his little wife, a mere child, was in labor and having a very difficult time and the untrained barbers’ wives had said that they could do nothing for her, and asked if I would go and help her. I told him that I knew absolutely nothing about midwifery cases but that my father was a doctor and that when he returned from a call he would gladly come and help. The man drew himself up and said, “Your father come into my caste home and take care of my wife! She had better die than have anything like that happen.”

Later, I took him over to my father’s study and together we pleaded with him and I told him that I would do everything in my power to help his wife, with my father if he would only let us come I would be an assistant! Still, he refused. Father also urged him, but he went away, apparently very unhappy because I could not help. I went to my desk very much stirred by that first encounter. After a time I heard steps again on the verandah and jumped up, hoping that the man had returned to take my father and me, but instead of seeing the Brahmin gentlemen, I saw a Mohammedan who had come to see me, and I was horrified to hear the same plea from him. His wife was dying, a mere child, and would I come and help? Again, I said I knew nothing about midwifery cases. I took him to my father, and we both reasoned with him and I said that I would go with my father who was a doctor, and do what I could to help. A scornful answer made my heart sad. He utterly refused saying that no man outside his family had ever looked upon the face of his wife. “She had better die than have a man come into the house,” he said.

Again, my father and I urged him to allow us to come, but again he refused repeating that she had better die than have a strange man look upon her face; and he left. I went back to my room with my heart so burdened that I hardly knew how to overcome it. After some time of thinking and trying to get my mind back onto my book, I again heard footsteps, and, running to the door, looked out to see if the second man had come back, but again I was more than horrified to have the same plea coming from a third man, a high-caste Hindu. He refused just as the others had done, and vanished in the darkness.6

The Conflict

I could not sleep that night—it was too terrible. Within the very touch of my hand were three young girls dying because there was no woman to help them. I spent much of the night in anguish and prayer. I did not want to spend my life in India. My friends were begging me to return to the joyous opportunities of a young girl in America, and I somehow felt that I could not give that up.6

The monk said, “I cannot return. It is so beautiful here. So much sunshine and beauty and love. I feel so close to you and God here. The sin, the dirt, the foulness are so great. I cannot return to it all”, and he prostrated himself at His Master’s feet.8

I went to bed in the early morning after praying much for guidance. I think that was the first time I ever met God face to face, and all that time it seemed that He was calling me into this work. Early in the morning I heard the ‘tom-tom’ beating in the village and it struck terror in my heart, for it was a death message. I sent our servant, who had come up early, to the village to find out the fate of these three women, and he came back saying that all of them had died during the night. As a funeral passed our house during the morning, it made me very unhappy. I could not bear to think of these young girls as dead. Again I shut myself in my room and thought very seriously about the condition of the Indian women.6

The Surrender

“…and after much thought and prayer, I went to my father and mother and told them that I must go home and study medicine, and come back to India to help such women.” 6

The Consecration

The Monk’s Story continues:

The Master stooping over him, lifted him up and looking into his face said, “My son I have need of Thee down there. Come let us go together to the village where the need is so great. Learn to love.” And the Master vanished. After long prayer the Monk arose. Going into his little hut, he gathered up his belongings. And saying farewell to all that had been so beautiful, so lovely, he went back to the village. And he found it needed him more than it needed him before. But he gave himself utterly to serving those people who needed him so sorely.8

Stages on a Journey

Beginnings

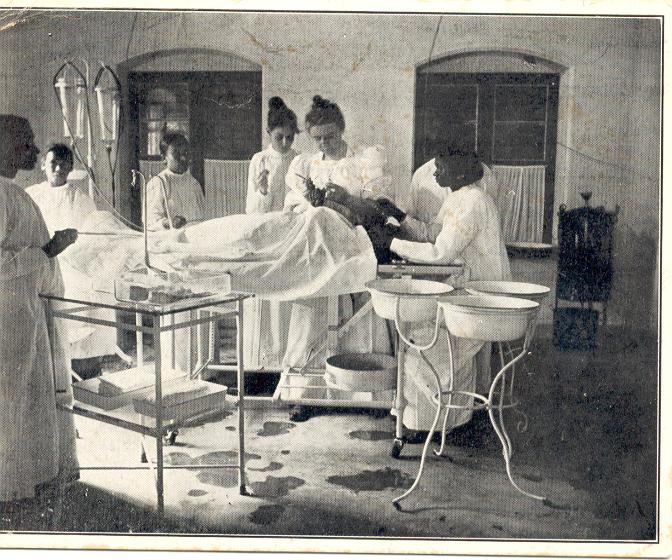

Ida went to medical school in Philadelphia and Cornell. Towards the end of her training, Louisa Hart, working in Ranipet, pointed out the need for a hospital for women and children in Vellore. Efforts at fundraising were disappointing until a week before Ida was to set sail, Robert Schell gifted the entire amount she needed to build the hospital. Ida reached Vellore on 1st January 1900, starting internship by observing and assisting her father in medical work. His sudden death in April left Ida bereft of father and mentor and helpless to cope. But a few weeks later, she began with the little she had: a few months of experience, a 10X12 foot room in the mission bungalow for a dispensary, the cook’s wife as an unskilled assistant, and a horse buggy to visit patients at home. Small beginnings and the trust of patients led to more: two beds in the guest room, a few huts for inpatients, (Fig.2) and in 1902, the forty-bed Mary Taber Schell Hospital, (Fig.3) supported by the Reformed Church of America.6,7

Co-workers and trainees: innovation and collaboration to meet needs

As the Schell Hospital grew, it needed more staff. (Fig. 4) A course in compounding was started in 1905. Delia Houghton was invited to join as Nursing Superintendent and start a “lower grade” nursing school. After long years of being the only doctor facing an impossible load of maternity, surgical, and general cases, Ida realized that she needed to start a medical school for Indian women. It was an audacious idea with one doctor, forty beds, and no classrooms. But interdenominational commitment towards a Union Missionary Medical School for Women and the support of the British Government enabled her to begin the LMP (Licentiate Medical Practitioner) course for Assistant Surgeons. Ida selected her first batch of eighteen girls and began in rented classrooms on Aug 12, 1918. In the first government exams, Ida’s protégés made her proud by securing the best results in the Madras Presidency (also known as the Madras Province).6,7

Stability, buildings, and traditions

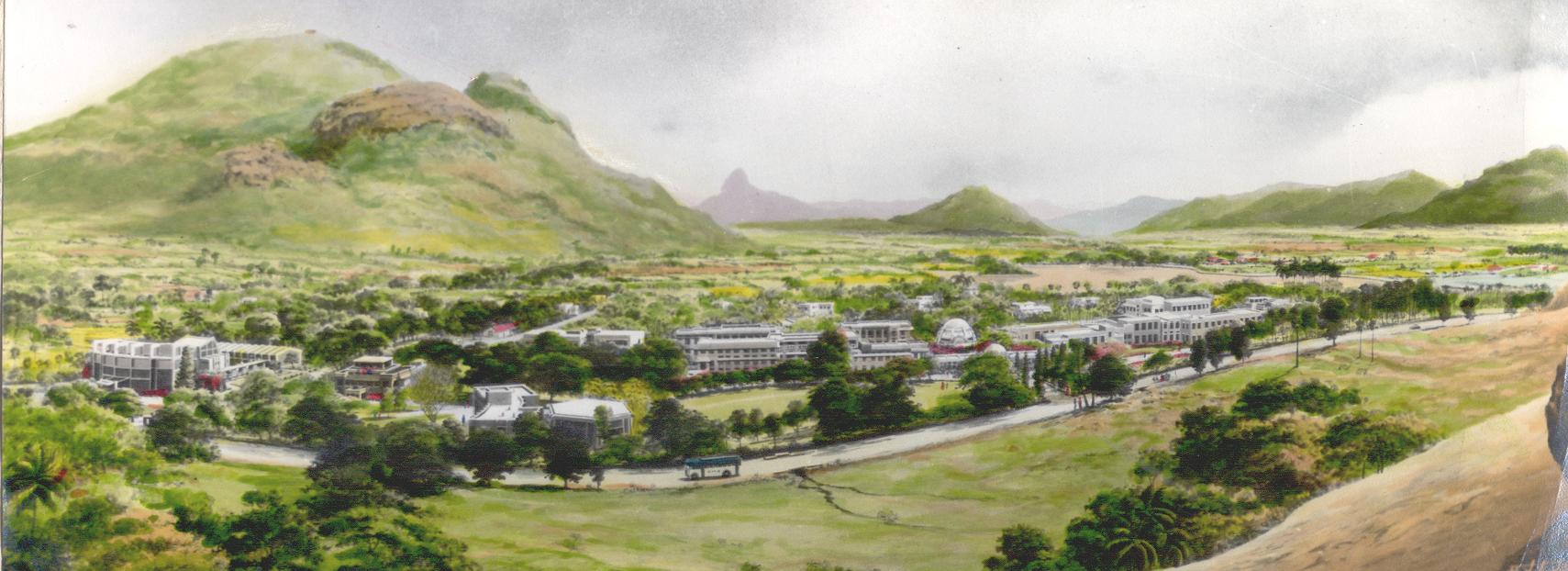

An interdenominational fundraising drive by women in America and Britain raised funds for the medical school. A teaching hospital was built by 1928, and by 1932, a beautiful residential college campus arose on the outskirts of the town. Here, Ida tried to capture the magic of her years in Northfield; students and staff lived, studied, played, and prayed together. Traditions of worship and celebration from those early years continue to enrich student life to this day.6,7(Fig. 5)

A crisis and the inadequacy of old ways

By 1937, the women’s medical school was in its twentieth year. That year brought a government ruling that the Assistant Surgeons course was to be abolished. Schools that could not upgrade to a university degree would be closed. The ruling was intended to raise the standards of medical training, but it did not make allowance for the scarcity of human and material resources. Since the early 1930s, Vellore had hoped to upgrade to an MBBS course, but the economic impact of the Depression prevented that. Similar constraints had forced the Christian Medical Association of India (CMAI) to postpone their plans to build the first University level Christian Medical College for men and women in Allahabad.12,13,14

The government did not extend the deadline, and the school had to stop taking new students in 1938. The option of partnering with the CMAI to create a single co-educational college in Vellore was considered and put aside. (Fig. 6) Ida’s supporters and Ida, herself, believed that would be a betrayal of the original calling to provide women doctors for women. They were confident that as they had done in the past, they would again find the necessary resources.

However, by 1941 only thirty-one students in the final year of the Assistant Surgeons course remained. Once the student body, left the school might never open again. 10 In an effort to prevent this, the limited resources available were used to expand the pre- clinical teaching facilities and permission was obtained to start a premedical course. In 1941, Ida Scudder sailed for the USA to raise money to save the school, double the number of hospital beds, and to find twelve new professors with higher teaching qualifications.7

God’s way: cast the net on the other side

These efforts were unsuccessful. The first batch of women who had joined in 1942 for the premedical part of University MBBS course had to be sent to government hospitals in Madras for clinical training, as Vellore did not have the requisite number of beds, laboratories, or trained faculty. Fundraising again in her seventies, weary Ida meditated often on John 21, believing resources would somehow become available.

“The disciples went fishing, worked all night but caught nothing - sad, hopeless, tired, discouraged, well-nigh desperate. At the break of day, Jesus stood on the shore. ‘Throw your nets on the other side.”15 The staff working in India urged Ida to take up the CMAI‘s offer to work together for co-education.14 Old allies in the USA remained opposed.7 At this impasse, Ida realized that God wanted her to go beyond her original call. The closed door to women’s education, the open door to co-education, was the signpost to the other side. A near breakdown became the breakthrough. In 1943, she assented. The Christian Medical Association of India and Vellore coordinated efforts, and recognition for clinical training for the MBBS course was obtained in 1945. In 1947, as India’s first Christian MBBS college, the institution opened its doors to co-education. (Fig. 7) It also started the country’s first university course in nursing. 13,14,16,17

Breaking and remaking

These ups and downs may resonate with the experiences of many who have journeyed with God. As they obeyed, they received prompting and provision, one step at a time. Threads came together transcending boundaries of time and space. The work grew. Then, when things were flourishing, unexpected shattering events taught them, through breaking and remaking, that God’s ways were not their ways. (Jeremiah 18:4). They were called to depend, not to be limited by past experience and boundaries, but to remain open to God’s greater purpose.

The Impact

It was up gradation to MBBS, coeducation, and the arrival of faculty like Robert Cochrane, John Carman, Paul Brand, Edward Gault and others from India and abroad that enabled Vellore to develop postgraduate courses, higher specialties, and research. It moved from being a modest hospital for women and children to a premier teaching hospital of independent India. The hospital that had begun as a one room clinic became the first in India to perform open heart surgery, neurosurgery, renal transplants, and bone marrow transplants. Equally, it led the way in neglected areas such as leprosy work, community health, rehabilitation, and mental illness. Nursing and medical schools of high repute, a hospital that sees 6000 patients a day, campuses scattered over many hundreds of acres, and alumni around the globe carry on this legacy. 18 (Figs. 8, 9).

Ida was privileged in her lifetime to see the fruit of her obedience. Her parable continues:

A change came over the village. Sin in time gave way to right living. The sorrow and suffering were replaced. All, all was changed. Because one consecrated young man gave himself to working with the Master for those who needed him. Schools, churches, hospitals were organized and Christ dwells among them, through His faithful loving service to his loving Master.8

Ida never imagined what her first ‘Yes’ would lead to. When she looked back at her journey she marveled at how God’s indwelling presence had led her, one step at a time: “I took only one step at a time, the step God showed me.”19

The Message

Ida’s parable ends with the commission: “Our Master may be preparing a place for you here in India or somewhere. The world is in need of loving workers today. May His voice come to you in a clear loving call — I have need of thee, my child.”8 May those who hear that voice find gladness and serenity in Ida’s discovery that, “When God has told you WHAT to do, He has already told you, you CAN.”8

References

- Waterbury JB. Memoir of the Rev. John Scudder, M.D. Thirty six years missionary in India. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers; 1870.

- Hoskins R. Clara A Swain, M.D: First medical missionary to the women of the Orient. [updated November 88 2004; cited 2014 May 1]. Available from: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/14017

- Glowrey, Mary (1887-1957). [updated 2009; cited 2014 May 1]. In: Trove. Available from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.party-742091

- Habig MA, Editor. The testament of St Francis. In: St Francis of Assisi, writings and early biographies: English omnibus of the sources for the life of St Francis. Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press; 1983. p.1.

- Scudder I. Glimpses of my life and work in India by Dr Ida Scudder [updated 2012 Aug 15; cited 2014 Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DT4BT7rdXTc

- Jeffrey P. Ida S Scudder of Vellore. Jubilee edition, Mysore: Wesley Press and Publishing House; 1951. [Narrative of the call quoted from pages 26-27].

- Wilson, DC. Dr Ida: passing on the torch of life. USA: Friendship Press; 1976.

- Scudder IS. The Monk’s Story [handwritten, undated document], quoted with permission [Ida Scudder papers, Collection MC 205 Series 1V. Schlesinger Library Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University]. Boston.

- West C. Medical women: a statement and an argument .London: J. A. Churchill; 1878, p.17.

- Scudder DJ. A thousand years in Thy sight. The Scudder Association. New York: Vantage Press; 1984.

- History of NMH [cited 2014 Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.nmhschool.org/about-nmh-history

- Minutes of the meeting of the executive committee of the National Christian Council Jan 1936. Nagpur: The National Christian Council of India, Burma and Ceylon; 1936.

- Brouwer RC. The varieties of religious experience in an Indian medical missionary: Belle Chone Oliver. Touchstone; May 2005; 23: 41-45.

- Georgia J. Legacy and challenge: the story of Dr Ida B Scudder. McNaughton & Gunn; 1994.

- Scudder IS. Notebook entry on 20 Feb 1942, CMC Vellore Archives.

- Oliver BC. Appeal for medical literature. Canadian Medical Association Journal. Jul 1945; 53:78.

- Proceedings of the ninth meeting of the National Christian Council. Nagpur: Office of the National Christian Council; 1944.

- Home of a Healing God. [updated Mar 13, 2010; cited 2014 Jan 28]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hdDKJK4pNWY

- Scudder IS, Speech in the late 1940s, soon after University recognition for MBBS was obtained, at a public meeting in Tindivanam, the place where she had received her call over half a century earlier. Cited by Inbanathan AE in the Souvenir, Jubilee Celebrations, Aug 12, 1960, p 141.