ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Future of Christian health services – An economic perspective

Steffen Flessaa

Abstract

Although Christian Health Services have a proud history of healing and compassion especially in developing countries, their future is affected by secular changes in the financing and provision of health care services. However, the nature of life as it is evolving in modern society promises a need for the capacity to deal with increasing dynamics, complexity and uncertainty. In these circumstances the potential capacity of Christians in their institutions and churches to provide Unconditional Reliability suggests a new opportunity. The components of Unconditional Reliability and how they affect the portfolio of Christian Health Services is explained. Effective Christian Health Services will require appropriate analysis of their portfolios.

Introduction

Christian health care services can be proud of their history: millions of people healed, suffering reduced, and contributions made to political, social, and economic development, particularly in developing countries.1 However, as early as 1964, the “Healing Ministry in the Mission of the Church” was challenged2 with the realization that a doctor–oriented “healing-factory” was not in line with the Christian call for shalom, wholeness, and community–orientation.3, 4 The Christian Medical Commission, founded in 1967 in Tübingen, Germany, propagated a community–based concept of Christian healing. This concept had a strong influence on the development of the primary health care philosophy that became known as the Declaration of Alma Ata, created by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1978.5, 6

At that time, leaders of mission organizations and diaconal institutions argued about the characteristics and quality of Christian health care services, but not at all about its relevance or future. In the past, it had always been clear that they were needed and that no alternative existed. In many places of the world, Christian institutions had a monopoly on modern health care, i.e., without church-run hospitals, dispensaries, and preventive services, the population had no access to modern health care at all. Today, the situation has changed. In particular, the poor seek fast and easily accessible health care from private providers in cities, and even in the rural areas of poor counties, there is frequently competition with private practitioners.7 The argument “if we are not there –nobody is there” has changed to “if we are not there ” others will provide the services”. This is in particular true for developed countries where the majority of the population is covered by health insurance, but it is also true for more and more developing countries.

Thus, we have to ask whether Christian health care services will have or should have a future. Since private and government providers offer professional and accessible health care services, a new discussion of the distinctiveness and the rationale of future existence of Christian health care services is called for. Cum grano salis: is there still a need for Christian health care services? Do they have a future?

This paper addresses these questions from an economic perspective, i.e., it covers only one dimension of the reality. However, as many Christian health care providers offer their services in a competitive market, economics is a tremendously important dimension for the future of these providers. The following section analyzes the properties of modern societies and concludes that “unconditional reliability” – as the distinctive feature of Christian health care services – is still of high relevance. It goes beyond “technical-functional” healing and constitutes a resource for the future. Next, we analyze the portfolio of Christian health care services in order to determine the most appropriate service program of these institutions. The paper closes with some conclusions.

Unconditional Reliability in Modern Society

In order to understand the role and future of Christian health care services we have to under-stand their role in a competitive health care market. Generally, a market justifies and supports the existence of a market element if it produces a value for the entire population. Consequently, we have to ask what value Christian health care services produce that is unique or at least more likely to be efficiently produced by these providers than by any other. In order to determine the relevant value of Christian health care providers for the society and economy we have to reflect on the characteristics of modern societies.

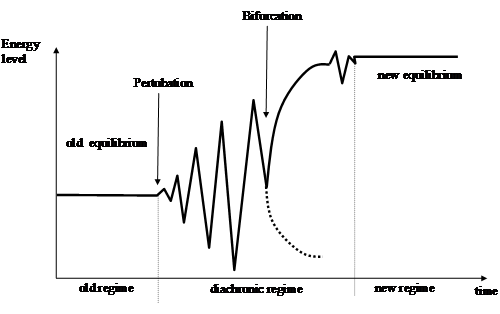

Modern societies and the life of individuals are characterized by continuous change. As Figure 1 shows, old system regimes are disturbed by perturbations and become unstable. These perturbations can be internal or external, technical, organizational, or societal innovations. If the perturbation is strong enough, the system evolves into a crisis until it reaches a “point of no return,” the bifurcation point. Here, it is obvious that nothing will remain as it was, but it is not clear how the new system regime will look. Ideally, the system reaches a new steady state at a higher energy level.

Figure 1. System regimes 8

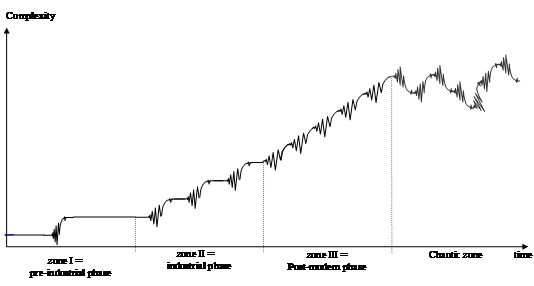

The length of the stable steady-state equilibrium between two diachronic regimes determines the stress on society and individuals. As Figure 2 indicates, the time can be very long (Zone I). In the Middle Ages, for instance, rules, technologies, and social strata remained constant sometimes for generations. During the industrial era (Zone II), the number of changes and crises markedly increased. However, the synchronic phases remained long enough so that a complete stabilization (“freezing”) of organizations, societies, and individual lives became possible. Consequently, stabile meta–structures such as strong organizations, rules, and hierarchies were possible and required. However, if the frequency of changes and crises increases even more, the synchronic phases will become so short that no steady state will be possible. As soon as a system comes out of a crisis, the next perturbation is waiting. Thus, no fixed rules are possible; instead, ad-hoc decisions and structures are required. Decisions have to be made in the micro–structure (on the grass root level), but need multiple information inputs, so that networks become extremely important (Zone III). Finally, this can lead to a situation where phases and directions cannot be distinguished (Zone IV). New major perturbations appear before a new macro structure can be established, and the system falls into destructive chaos.9

Over the last fifty years, we see that the number of perturbations, changes and crises, are steadily increasing. Rieckmann analyzes these developments and points out that modern societies are characterized by three features summarized in the term “Dynaxity”: complexity, dynamics, and uncertainty.9,10 Complexity means that the number of elements in a system, the number of relevant environmental systems, and the number of relations between elements in the system or between systems and the environment are increasing. In the 1960s, for instance, most markets were local. Providers were mainly “stand-alone” institutions connected primarily with their catchment population and the local government. Modern business units and individuals, however, have a tremendous number of interdependencies with highly mobile clients, globalized suppliers, civil society, worldwide competitors, customer rights organizations, lawyers, tax consultants, international NGOs, etc. . . The complexity has markedly increased.

Dynamics can be expressed by the speed of the development of new elements and new relationships in a system. A system is dynamic if it not only develops new relationships with other organizations but if the time interval between the creation of new relationships becomes shorter and shorter. At the same time, old foundations deteriorate, and there seem to be no more safe harbors on which society and individuals can rely. Regulations, customers, supplier relationships, and traditions change as rapidly as knowledge.

The consequence of this is that the predictability of changes in time becomes more difficult, i.e., uncertainty increases. This either means that possible conditions of the environment are completely unknown or that their realization can only be assessed by likelihood. Nothing is certain any more, stochastics is the art of the future, and decision-theory is mainly dealing with uncertainty. Enterprises, other organizations, societies, and individuals are left with high risk in all activities and life in general.

Figure 2. Dynaxity11

Dynaxity Zone III as the description of a post-modern society and economy makes high requirements on the individual. 12,13 One must be able and willing to understand highly complex systems, to accommodate rapid changes, and to take risks under extreme uncertainty. The 21st century places a high demand on one’s personality. Individuals and society require a resource that gives them the capability of dealing with this complexity, dynamics, and uncertainty. Which resource could make them willing to take the risks of modern life and prevent the drift towards destructive chaos in the presence of complexity, dynamics, and uncertainty? Obviously, this is only possible if central areas of human lives are protected by unconditional reliability14 Thus, modern society and economy call for un-conditional reliability as a resource of modern life.

This unconditional reliability has different dimensions. The physical dimension requires unconditional protection of the human body by reliable health care services. Only if people can be sure that their physical needs will be attended to under all conditions of life will they be able to take the risks of life. A young man willing to become an entrepreneur must know that there will be a comprehensive basic health care package available for him, even if risks materialize and he goes bankrupt with a fortune of debts. Consequently, reliable health care services for every member of the society, a core of universal health coverage, are not a luxury but a resource of unconditional reliability in a modern world. Christian health care services contribute to this unconditional reliability as a feature of the society the world can rely on that will offer care whatever happens.

Unconditional reliability also has a social dimension. Dynaxity zone III is full of networks and relationships – but people have the longing to be more than a business partner in a network. They want to be loved and respected irrespective of their personal success. Nobody can “survive” and invest himself fully into a network economy or society unless he can fully rely on sources of respect for his dignity and of love for him as an individual even if he fails in life. Consequently, reliable health care services, where the dignity of human beings is respected under all conditions, are not a luxury, but a resource of unconditional reliability. Christian health care services have the unique calling to make this respect and love perceivable irrespective of their clients’ success or failure in life or their ability to pay.

Finally, unconditional reliability also has a spiritual dimension. Human beings seek meaning, and this includes phases of sickness and dying.15 Every human needs the time and space to discover the meaning of suffering and dying without fear, accompanied by relatives and friends and without terrible pain. People cannot dare to invest their lives into the modern economy and face all the risks of Dynaxity zone III unless they can believe that there is spiritual support in the crucial situations of life. Christian health care services have the unique opportunity to provide this support, help the seeker, and provide answers that offer reliability beyond this life.

In a nut-shell, one can conclude that individuals, the economy, and the society have to be assured they can rely on functional, humanitarian, and “warm” health care services. Otherwise, they cannot risk full dedication of their lives and work in Zone III in a post-modern society. Christian health care produces a crucial value in Dynaxity Zone III: unconditional reliability in all dimensions of life. The consequence is trust as the “moral capital” of human life, economics, and societal development.16 It is the trust in one’s capability, in others, in the social system, and in God that is so crucial for our future. Without trust, society and economy will collapse.17 But the economy cannot produce this trust. Instead, trustworthiness must be experienced in families, friendship, churches, and health care services.18 An economy and society in Dynaxity Zone III induces stress on the “flexible man” that can be survived only with a firm foundation of unconditional reliability.19,20 Unless we want to risk a trust crisis, we need this firm foundation.21 Christian health care services can produce this utmost important value: trust based on unconditional reliability.

However, the production of trust based on unconditional reliability in Christian health care organizations is not by default. In other words: we must make wise decisions in our portfolios and processes in order to guarantee that Christian services can fulfil this demand. In the next section, we will analyze the conditions of this function of Christian health care providers for the society.

Portfolio and Process Management

It is obvious that the physical dimension of unconditional reliability does not necessarily have to be fulfilled by Christian services. Government and private for-profit enterprises are capable of performing this function as well. Only if the supply of services provided by these competitors is insufficient do Christian health care services provide a value that would not exist without them. The social dimension is frequently addressed by professional quality management. Respect for the dignity of human beings is not unique to Christian services.

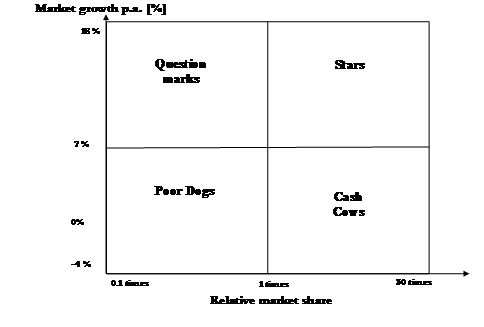

Consequently, we have to analyze the port-folio of Christian health care services to determine where they must engage themselves to have a unique value for the society. The analysis of service portfolios is a standard of business administration that has to be adapted for this analysis.22 The most well-known system for commercial industries is the so-called “BCG-matrix” that was introduced in 1968 by Boston Consulting Group.23 It assumes that any enterprise (including church-run hospitals) has a portfolio of service. Some products have growing turn-over and are in growing markets, others persist on shrinking markets and have declining sales. Some products produce a lot of cash flow, and others need cash flow to grow. The BCG-matrix gives strategies to determine the products in which to invest.

Figure 3. BCG-matrix23

As Figure 3 shows, the axes of the matrix are “relative market share” (relative in comparison to the biggest competitor) and “market growth”. It contains four fields with four strategy norms:

- Poor dogs: Low relative market share, low market growth. Strategy: give up.

- Question marks: Low relative market share, high market growth. Strategy: further research, promising candidates should be developed further.

- Stars: High relative market share, high market growth. Strategy: further investment to maintain success.

- Cash cows: High relative market share, low market growth. Strategy: no more investment, use cash flow to support question marks.

Christian health care services cannot base their portfolio decisions on the BCG-matrix. This is due to the fact that these nonprofit-organizations do not seek profit but want to fulfil their Lord’s command of love by caring for the sick and needy. Consequently, the dimensions have to be adjusted. Schellberg developed a portfolio matrix for nonprofit-organizations and recommended the dimensions “ethical mission” and “refinancing.”24 Flessa and Westphal applied this concept to diaconal institutions and used the dimensions of “diaconal mission” and “re-financing.”25 The first expresses the priority within a Christian goal system, the latter the possibility to break-even within the existing financing mechanisms. A service is usually of low diaconal priority if the Christian service provider offers exactly the same services like everybody else. Figure 4 shows the respective portfolio-matrix.

Figure 4. Portfolio-matrix of diaconal institutions 25

As before, four strategy norms can be derived:

- Touchstones: These services can only be offered with a financial deficit, but they have a high diaconal priority. These services are usually innovative so that there is hardly any competitor on the market. At the same time they are not yet financed by (health) insurances or the government. Strategy: investment and development.

- Stars: These services are completely refinanced by fees or Government subsidy. They have a high diaconal priority. Strategy: further investment.

- Cash Cows: These services are completely refinanced by fees or Government subsidy, but they have a low diaconal priority. Strategy: These services should be used to produce cash flow for the development of touchstone services.

- Goiter: These services can only be offered with a financial deficit. At the same time they have a low diaconal priority. Strategy: give-up.

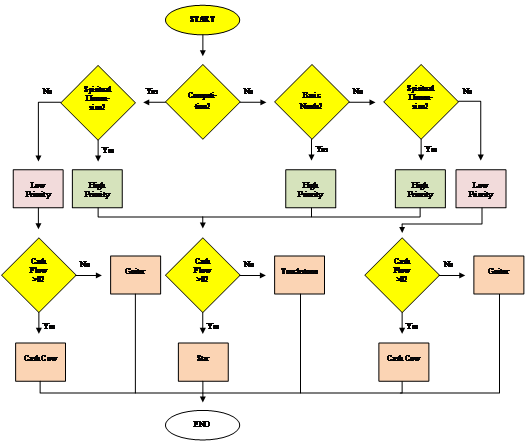

It is crucial to analyze the service program of Christian health care services in order to determine to which field of the matrix they should be assigned. Figure 5 exhibits a decision-chart for the portfolio analysis. In a first step, we analyze the competitiveness, i.e. we analyze whether Christian health care providers are monopolists or have total or partial competition. If no other provider offers the services (such as it was for generations in rural Sub-Saharan Africa), the Christian provider must give a high priority to this service. If there is competition, we have to analyze whether the alternative supply is sufficient in quantity and quality to satisfy the needs of the population. It can be shown that nonprofit organizations will have – without other changes – a tendency to produce a higher quantity of services as they try to achieve their output maximum which is still recovering their cost while a for-profit provider would maximize its profit margin.26 Under the condition of an S-shaped production function, this is less than the quantity of nonprofit organizations.

Health care markets are structurally imperfect, i.e., customers cannot easily assess the quality of services, and the number of service providers is limited.27 Under this condition, the market does not necessarily guarantee that the produced quantity is sufficient to satisfy all basic needs, including basic health care. Supply provided by government and for-profit organizations can be insufficient so that Christian services should consider supporting the population with additional supplies. Here, Christian services are competitors on the market, but their existence is crucial.

However, even if the supply is insufficient, it can be that there is no need for Christian providers to fill the gap. Instead, we have to conduct a second step in analysis and appraise whether the needs justify Christian engagement. For instance, there might be a tremendous demand for jewelry, but this does not call for Christian provision. Only if the physical existence or the dignity of human beings are threatened will Christians be urged to intervene. In all other cases, we can leave the satisfaction of needs to the free market or just accept that not all needs on this earth have to be satisfied.

Nevertheless, the situation is different if the spiritual dimension is considered as decision-relevant. Generally, all services and commodities have different utility dimensions. If we can separate these dimensions (e.g., physical and spiritual dimension), different providers can provide the services. For instance, a private for-profit hospital can do the operation, and the spiritual care can be taken by a pastor outside a Christian institution. However, if the spiritual dimension cannot be separated from the physical, Christian health care providers have a high incentive to fulfil even the physical needs of their clients. In this case, it makes sense to have a Christian health care provider and not just Christians “visiting” other providers for spiritual care. This requires that the personnel be capable and willing to perform not only technical-functional tasks, but also offer spiritual services (e.g., prayer with the patient) by one and the same person (una persona).

Figure 5. Portfolio Analysis28

Based on Figure 5, we can distinguish categories of Christian health care services and attach the service program to the portfolio-matrix.28 Services that address existential needs and that are not sufficiently provided by the competitors have a high priority. Services where spiritual and physical dimensions cannot be separated also have a high priority, even if other competitors suffice to satisfy the physical needs. All services that can be provided by others in the very same way should have a low priority.

At the same time, we have to see that Christ-ian health care providers could have elements in their portfolio that have a low priority, but produce cash flows to subsidize high-priority fields. These Cash Cows are necessary to finance Touchstones with high priority but low financing. Services which neither produce positive cash flow nor have a high priority are as useless as a Goiter and should be taken out of the portfolio at once. Services that can be fully refinanced and have a high priority are Stars.

Figure 4 shows the respective portfolio matrix.25 Christian health care providers are asked to analyze their portfolios to realize whether they produce the value of unconditional reliability in each quadrant of the matrix. Without doubt, the ideal producer of trust is the touchstone: People realize that Christians are aware of the current (health) problems and provide solutions irrespective of financing. Christians take their own funds – cash flow from cash cows or donations – to offer services seen as relevant and needed. Almost all Christian health care services were touchstones at the time of their inauguration. And until today, many Christian institutions are touchstones, in particular, in rural Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Here, it is decided whether Christian love and solidarity is really more than just a tradition. And here, it is determined whether the world perceives that it can rely on Christianity.

It is obvious that this calls for Christian solidarity, i.e. richer Christians within one country and worldwide are called to support the Touchstones with their giving. At least in countries with Universal Health Coverage (like in most European countries), we have become accustomed to the assumption that diaconal work is financed by fees or government contributions. However, financing touchstones –in particular in absence of Cash Cows – will require additional financing. If we assume that the social situation is dynamic (i.e., that new needs will arise) and that not all needs can be covered by the government of a social insurance, this is also a call for a new reflection on financial stewardship for each Christian and the church as a whole.

The development of social security frequent-ly makes Stars (which are of high priority and are fully financed) out of Touchstones. However, full financing induces competition. The Christian provider will lose his monopoly, and unless he manages to stress the spiritual component, the original Touchstone will soon become a Cash Cow. The amalgamation of physical and spiritual dimensions will produce unconditional reliability for the society. Every human being can rely on Christian health care services to not only treat his body but also support him on his journey of finding meaningful answers for the important questions of life. The search for meaning in life, suffering, and dying are not only luxuries for the rich and successful minorities, but are integrated into Christian health care services.

In the worst case, the Cash Cow cannot compete with private for-profit providers and runs again into the loss–zone. At the end of the cycle, a service remains that neither has a Christian priority nor produces cash flow for re-financing Touchstones.

In other words: Christian health care ser-vices must “live above the line” by focusing on services with a high priority: either by providing services in places where nobody else wants to work or by closely linking the spiritual and the physical dimension of health. The latter is definitely an issue of process management, i.e., the future of Christian health care services and their role in producing ultimate reliability as a source of trust for the society and economy depending on the dedication of the Christian health care staff.

Conclusions

Based on this analysis, we can conclude that Christian health care services can only be different and fulfil their function of producing unconditional reliability if the spiritual dimension of healing is strengthened. Therefore, we have to ask whether the reality of Christian health care institutions globally reflects the reality of the “congregation as the healing body of Christ” or our spirituality is reduced to an ethics committee – just as it exists in all governmental and private for-profit hospitals.

The fulfillment of the original function of Christian health care providers requires a spirituality that is interwoven in daily processes within these institutions. This is primarily not a question of quality management but of staff who are personally deeply grounded in the truth of the gospel and have a relationship with the living God. The spiritual dimension of health care requires spiritual co-workers. Their love, dedication, faith, and trust determine whether Christian health care providers really make a difference. This also requires spiritual leaders. Their spiritual life, motivation, and ability to have a vision, to motivate others, and to earn their trust determine the foundation of spirituality in Christian health services. And, it determines whether co-workers can make Christian health care services distinguishable and whether there is still a need for Christian health care services in the future.

This paper started with the statement that we will only address the economic dimension of Christian health care. Everybody who runs a Christian hospital or program knows how much our church work is “in this world” with all its limitations and complexities. At the same time, we have shown that the functionality and sustainability of our services increasingly depend on the Christian spirituality of our staff and leadership. Thus, the visible and the invisible church are both to be reflected in our work. Finding the right balance between market and godliness, between economic constraints and the indefinite resources of God remains a challenge. However, it is not an academic discourse but a very practical debate that affects the future of Christian health care services worldwide.

References

- Grundmann CH. Gesandt zu heilen. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus; 1992.

- Newbigin L. [Editor’s Note]. Int Rev Missions. 1964;53:250.

- Scheel M. Kann Glaube heilen.Breklumer Verlag: Breklum; 1988.

- Fountain DE. Health, the bible and the church. Wheaton: Billy Graham Center; 1989.

- McGilvrary JC. The quest for health and wholeness. Tübingen; 1981.

- Diesfeld HJ, Falkenhorst G, Razum O. Gesundheitsversorgung in Entwicklungsländern. Medizinisches Handeln aus bevülkerungsbezogener Perspektive. Berlin et al.: Springer; 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-56648-6

- IFC. The business of health in Africa. Washington D.C.: International Finance Corporation; 2008.

- Ritter W. Allgemeine Wirtschaftsgeographie. Eine systemtheoretisch orientierte Einführung. 3., überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage ed. München: Oldenbourg; 2001.

- Rieckmann H. Management und Führen am Rande des 3. Jahrtausends. Frankfurt a.M.: Lang. ; 2005.

- Rieckmann H. Führungs-Kraft und Management Development. München, Zürich: Gerling; 2000.

- Fleßa S. Grundzüge der Krankenhausbetriebslehre, Band II. München: Oldenbourg; 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1524/9783486855906

- Koslowski P. Wirtschaft als Kultur. Wirtschaftsethik und Wirtschaftskultur in der Postmoderne. Wien: Passagen Verlag; 1989. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-57502-0_4

- Karst K, Segler T. Postmoderne - eine Standortbestimmung. In: Karst K, Segler T, editors. Management jenseits der Postmoderne. Springer: Heidelberg et al.; 1996. p. 11-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-87100-8

- Schweer MK, Thies B. Vertrauen als Organisationsprinzip. Bern: Huber; 2003.

- Graf H. Mit Sinn und Werten führen: was Viktor E. Frankl Managern zü sagen hat. Münster u.a.O.: LIT Verlag; 2005.

- Lachmann W. Ausweg aus der Krise: Fragen eines Christen an Marktwirtschaft und Sozialstaat. Witten: R. Brockhaus; 1984.

- Albach H. Vertrauen in der ökonomischen Theorie. J Inst Theor Econ. 1980: p. 2-11.

- Röpke W. Ethik und Wirtschaftsleben. In: Stützel WH, editor. Grundtexte zur Sozialen Marktwirtschaft. Stuttgart, New York: Gustav Fischer; 1981. p. 49-62.

- Habermas J. Hat die Demokratie noch eine epistemische Dimension? Empirische Forschung und normative Theorie. In: Habermas J, editor. Europa. Kleine Politische Schriften. XI ed.Berlin: Suhrkamp; 2008. 138-91.

- Sennett R. Der flexible Mensch. Die Kultur des neuen Kapitalismus. Berlin: Bt Bloomsbury; 1998.

- Siegenthaler H. Regelvertrauen, Prosperität und Krisen. Die Ungleichmäßigkeit wirtschaftliche und sozialer Entwicklung als Ergebnis individuellen Handelns und sozialen Lernens. Tübingen: Mohr; 1993.

- Fama EF. Portfolio analysis in a stable Paretian market. Manage Sci. 1965;11(3):404-19.

- Hambrick DC, MacMillan IC, Day DL. Strategic Attributes and Performance in the BCG Matrix–A PIMS-Based Analysis of Industrial Product Businesses1. Acad Manage J.1982;25(3): 510-31.

- Schellberg K. Betriebswirtschaftslehre für Sozialunternehmen. Augsburg: Ziel; 2004.

- Flessa S, Westphal J. Leistungsprogrammplanung karitativer Nonprofit-Organisationen als Instrument des Ethik-Controlling*: Eine exemplarische Analyse des Portfolios diakonischer Sozialleistungsunternehmen. Vorpommern. Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts-und Unternehmensethik.2008;9(3):345.

- Fleßa S. Betriebswirtschaftslehre der Nonprofit-Organisationen. Betrieb Forsch Prax. 2009;61(1): 1-21.

- Henderson J. Health economics and policy. Ohio, USA: South-Western College Publishing, Thomson Publishing Company; 1999.

- Fleßa S. Prozess- und Ergebnisprofilierung diakonischer Sozialleistungsunternehmen. Verkündigung Forsch. 2014;59(1): 38-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.14315/vf-2014-59-1-38