Figure 1: HTSP messages alongside available Government of India methods of FP

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Susan Otcherea, Varghese Jacobb, Abhishek Anurag Toppoc, Ashwin Masseyd, and Sandeep Samsone

a M.Sc. Maternal and Child Health, Project Director, Mobilizing for Maternal and Neonatal Health Through Birthspacing and Advocacy (MOMENT), World Vision, Washington, DC, USA

b MSW, Associate Director, PMO, World Vision India

c M.Sc. Disaster Management, Program Officer, World Vision, India

d M.Tech (Bio-Informatics), Program Officer, World Vision, India

e MBA, Program Officer, World Vision, India

Background: Uttar Pradesh (UP) is the most populous state in India. The maternal mortality ratio, infant mortality rate, and fertility rates are all higher than the national average. Sixty percent of UP inhabitants live in rural communities. The reasons behind the poor state of health and services in many areas of UP are inadequate knowledge and availability in communities of healthy behaviors, and information on available government health services.

Methods: World Vision, Inc. implemented a three-and-half year mobilizing plan for maternal and neonatal health through a birth spacing and advocacy project (MOMENT), partnering with local organizations in rural Hardoi and urban slums of Lucknow districts in UP. World Vision used print, audio, visual media, and house-to-house contacts to educate communities on timing and spacing of pregnancies; and the benefits of seeking and using maternal and child health services (MCH) including immunization and family planning (FP).

This paper focuses on World Vision’s social accountability strategy – Citizen Voice and Action (CVA) and interface meetings – used in Hardoi that helped educate and empower Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committees (VHSNCs) and village leaders to access government untied funds to improve community social and health services.

Results: Forty VHSNCs were revived in 24 months. Nine local leaders accessed government untied funds. In addition, increased knowledge of the benefits of timing and spacing of pregnancies, maternal child health, family planning services, and access to community entitlements led the community to embrace and contribute their time to rebuild and re-open 17 non-functional Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM) sub-centers. Seventeen ANMs received refresher training to provide quality care. Sub-center data showed that 1,121 and 3,156 women opted for intra-uterine contraceptive device and oral pills, respectively, and 29,316 condoms were distributed.

Conclusion: In Hardoi, UP, education using CVA and interface meetings are contributing to an increase in the number of government sub-centers that integrate contraceptive services with other services such as immunization and antenatal care. This brings care closer and makes it more accessible to women and children, reducing travel time and cost to families who would have otherwise sought these services from higher level facilities. Social accountability can help mobilize communities to contribute to improving services that affect them.

The state of Uttar Pradesh (UP) lies in the heart of India. With a current population of 204 million people, it has the second-highest fertility rate in the country: 3.3 children per woman. With 345 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births and an infant mortality rate of 50, Uttar Pradesh has among the highest rates in India.

The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM, 2005-2012) was launched by the Government of India (GoI) in 2005-2006 to provide effective health care to the rural population in the country, with special focus on states with poor health outcomes and inadequate public health infrastructure and manpower. UP is one of these states. The primary focus of the mission is to improve access to health care for rural people, especially women and children. The main goal of the NRHM is to reduce the infant mortality rate (IMR) and maternal mortality ratio (MMR) by promoting new-born care, immunizations, antenatal care, institutional deliveries, and postpartum care. Per the District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3), the national total unmet need for contraception was 20.5 percent, comprising 13.3 percent for limiting and 7.2 percent for spacing. It was estimated that across UP, the unmet need for contraception was higher than the national average (32.5 percent), comprising 21.9 percent limiting and 10.7 percent for spacing.1

The National Rural Health Mission foundation is built on community involvement in drawing village health plans under the auspices of the Village Health and Sanitation Committee (VHSC), making rural primary health care accountable to the community.1,2 MOMENT efforts contributed to the Government of India’s National Rural Health Mission goals.

World Vision implemented a three-and-a-half-year mobilizing plan for maternal and neonatal health through birth spacing and advocacy project (MOMENT), with a goal to improve maternal, neonatal, and child health (MNCH) by creating global and local enabling environments for quality maternal, neonatal, and child health service delivery and use. MOMENT was implemented in four countries: the United States, Canada, Kenya, and India. The objective in India was to strengthen community knowledge on healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies/family planning (HTSP/FP), to enhance maternal, neonatal, and child health services, to engage the community in improving service delivery, and to ensure the use of healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies/family planning methods in Hardoi and Lucknow districts. Kenya had a similar objective. The U.S. and Canadian implementation focused on mobilizing policymakers to become champions of sustained maternal, neonatal, and child health funding, and grow their understanding of the contributions to healthy timing, spacing of pregnancies, and family planning to ensure positive outcomes for mothers and their children. MOMENT was a World Vision project implemented in each of the four countries through its staff in collaboration with various government and local partners.

MOMENT operated in a phased approach in four blocks (out of a total of 19 blocks) of the rural Hardoi district, UP, which had a population of 391,000.3 The results of a population baseline survey in December 2013 highlighted culturally based issues that are important in all community-based programs. These include the mother-in-law’s and husband’s power over a woman’s health care-seeking behavior outside the home, and, therefore, low knowledge of the benefits of seeking and using maternal, neonatal, and child health, and family planning services. Geographic access to these services was out of reach for rural dwellers. Village committees and VHSNCs recognized by the government were not functioning, so villagers missed out on government entitlements.

To address low knowledge of maternal, neonatal, and child health, and family planning services, World Vision developed several social and behavioral change strategies that worked to educate the community. Social and behavior change communication (SBCC) was a health-promotion strategy that evolved from information, education, and communication approaches (IEC) to address contextual factors that prevented people from improving their health behaviors. The Health Communication Capacity Collaborative Initiative defines SBCC as, “…the use of communication to change behaviors, including service utilization, by positively influencing knowledge, attitudes, and social norms.” It goes on to say that, “SBCC coordinates messaging across a variety of communication channels to reach multiple levels of society…” 4

First, World Vision developed messaging leaflets on the importance of timing and spacing of pregnancies, and how to achieve these through the use of modern methods of family planning, using the Government of UP’s family planning messages (Figure 1). Accredited social health activists (ASHAs) made house-to-house visits to discuss and share messages with women, mothers, mothers-in-law, and husbands.

Figure 1: HTSP messages alongside available Government of India methods of FP

Messages on healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies

World Vision also created educational games, including Snakes and Ladders (Figure 2) and an electro-game (Figure 3). Both games could be played at home or in the community, having the innovation of mobility and the ability to be played by different age groups and genders. The electro-game was effective in attracting mothers-in-law, husbands, and men in learning about maternal, neonatal and child health, healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies, and family planning. Wall paintings with the healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies/family planning messages were placed strategically throughout the community.

Figure 2: HTSP Snakes and Ladders game

The information and education were imparted in the first year of the project to build trust and community engagement. In the second year, World Vision introduced the idea of social accountability, another key intervention in World Vision’s Citizen Voice and Action (CVA) social accountability strategy. CVA aims to increase dialogue between ordinary citizens and organizations that provide services to the public. It also aims to improve accountability from the administrative and political sections of the government (both national and local) in order to enhance the delivery of public services.5,6 In Hardoi, World Vision members met with several Gram Pradhans (GPs, village headman) to gain support and entry dialogue with members of the gram panchayats, mothers-in-laws, and husbands. They used the term “interface meetings” as this was more familiar to them. Initial dialogues with the latter groups also included ASHAs, auxiliary nurse-midwives (ANMs), the community development officer (CDO), and other people the GPs deemed relevant.

There were three main goals of these interface meetings:

The Government of India health facilities consist of government/municipal hospitals, community health centers, primary health centers, and sub-centers. They are the major sources of contraception for current users of modern methods, antenatal care, immunizations, and nutrition. Having functional ANM centers close to communities was a critical unmet need.8 With the potential reopening of ANM sub-centers, the MOMENT project also planned for and facilitated refresher training of ANMs in immunizations, nutrition, and counseling of family planning methods including intrauterine device insertion as per the government policies.

All these coordinated steps were geared to bring services closer to mothers, thereby increasing availability and access to integrated maternal child health, nutrition, immunization, and family planning services.

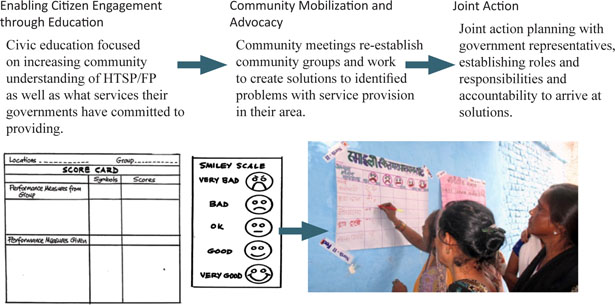

Citizen Voice and Action interface meetings are spearheaded by the Gram Pradhans and the VHSNC to bring community members together to discuss matters that concern them. The interface meeting has a government representative, and either a community development officer, an ASHA worker, an ANM, or all three depending on their availability. Together the group assesses community services, discusses solutions, and makes joint action plans on how citizens and the government can improve services. The process involves three stages: 1) educating communities, 2) community mobilization and advocacy, and 3) joint action planning (Figure 4). During the interface meeting, score cards are used during joint action planning and standard setting for joint accountability. The communities in Hardoi used their score cards to evaluate the quality and availability of services in their community; the services received or lack thereof from the service providers, elected leaders, and government representatives.

Figure 4: Interface meetings, citizen voice and action (social accountability strategy of World Vision Inc.)

Community education on the healthy timing and spacing messages yielded a rise in community knowledge of the healthy timing and spacing key message, “Wait at least 2 years after one pregnancy before trying for another pregnancy,” and the message (three-year gap between two children) from 28 percent, 190.4 (n=680) baseline to 83.8 percent, 514 (n=613) endpoint.

Through many meetings, MOMENT raised awareness amongst Gram Pradhans regarding the VHSNC’s existence, its roles, and responsibilities. Forty VHSNCs were revived during the latter 24 months of project implementation. The coordination between the Gram Pradhans, VHSNCs, the entire community, the auxiliary nurse midwife, and the community development officer has improved since the revival of VHSNCs and the convening of meetings.

Gram Pradhans have been equipped to request untied funds. Nine out of 17 village heads requested and received untied funds of 35,000 Rupees (US$562, 2016) from the government. The funds were used to refurbish, revive, and improve 17 abandoned ANM sub-centers. Physical work on the sub-centers included weeding, infrastructure work, painting, flooring, providing beds and curtains for privacy, ensuring water supply, and providing cabinets and books for recording client services. See Figure 5 for an example of an ANM center before and after refurbishment.

Figure 5: Birouli, Behendar block changes

Since the sub-centers were closed for many months and no service records were available until they were reopened in February 2015, data from ANM sub-centers started at zero. Women, children, and the community started using the sub-center for immunizations and antenatal care. MOMENT worked with the Hardoi health district by adding wall painting messages on healthy timing and spacing of preg nancies, and supporting auxiliary nurse midwives to gain refresher training in counseling clients on the different methods of government family planning services. Over the next 24 months, the 17 ANM sub-centers recorded use of family planning services (Table 1). By increasing availability and access to IUDs, oral pills, and condoms, they observed a modest increase in the use of IUDs and oral pills during the nine months of the second year. In addition, if they applied the couple year protection (CYP) calculation to the first 12 months (February 2015-January 2016), then the data showed 2,049, 105, and 159 couples on IUDs, oral pills, and condoms, respectively, as being protected from pregnancy.9

Culture is important to sustainable development and cannot be underplayed. Social accountability and education help mobilize communities to discuss and contribute to improving services that affect them. However, this requires time and effort, and cannot be rushed. A recent review suggests that social accountability and similar approaches “should be part of a long-term, integrated, iterative, and partnership-based approach to social change.”5

In the MOMENT project, community education and dialogue around HTSP/FP and maternal, neonatal and child health services helped community leaders and citizens in Hardoi understand the connection between timing and spacing of pregnancies, the relevance to health of mothers and children, and the importance of using modern methods of family planning. Empowering VHSNCs demonstrates how community members can advocate on their own behalf and improve the well-being of their community.

Social accountability in the form of CVA and interface meetings used in the MOMENT project contributed to the strengthening of partnerships and the implementation of existing Government of India (GoI), and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare policy guidelines for VHSNCs and Health Centers.7 In addition, using social accountability and engaging local committees, citizen voices, and actions, the GoI representatives and its systems helped contribute to the improvement and revival of ANM sub-centers, a public sector service. The process used is somewhat consistent with the World Development discussion paper that described social accountability in two ways: the tactical and strategic approaches. The paper described a theory of change for tactical approaches that assumed that “access to information alone (would) motivate localized collective action, which (would) in turn generate sufficient power to influence public sector performance.” The strategic approaches, on the other hand, used “multiple tactics, encourage(d) enabling environments for collective action for accountability, and coordinate(d) citizen voice initiatives with reforms that bolster(ed) public sector responsiveness.”10

The paper suggested that the evidence of impacts of strategic approaches was much more promising. The different social accountability approaches used in the MOMENT project were and are geared to ensure ownership, viability, and sustainability of the principles of community, village, and government engagement.

The reopening of the ANM sub-centers brought MNCH services closer to households. The integration with family planning services including the intrauterine device was aligned with GoI family planning services, and served to 1) increase access to this method of contraception and 2) reduce travel time, distance, and cost to families who would have otherwise sought these services at higher level health primary health center (PHC) and community health center (CHC) facilities or perhaps not at all. Evidence from projects showed that the use of these services could increase when there was a one-stop shop such as a maternal/child health/family planning/Immunization day clinic.11 As mentioned above, the DLHS-3 report showed the unmet need for spacing in Uttar Pradesh as 10.7 percent and so the work of MOMENT was an important contribution to increasing access to health care and reducing the 21.9 percent total unmet need in Uttar Pradesh.1 In addition, though GoI policy required auxiliary nurse-midwives’ to refer women and couples to PHCs and CHCs for other longer acting and permanent methods of contraception, they did not track the referrals made.

The role of the accredited social health activist and the auxiliary nurse-midwife, India’s community health workforce, in sharing the message of timing and spacing of pregnancy and providing family planning services cannot be underestimated; in fact, it highlights the support of and the need for community health workers as an integral part of strengthening the health system.12

Though the MOMENT project demonstrated an effective intervention to increase access to services in hard to reach areas, it did not come without challenges.

Finally, this MOMENT project activity demon strated the potential for increasing coverage and access to high impact maternal, neonatal, and child health/family planning services and practices should the Uttar Pradesh and Hardoi local governments, the Government of India, and other programmers build on our successes through the following:

The long-term impact could be improving the health status of women and children throughout India.