Figure 1. Themes in defining public health (percent; n=7)

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Jason Paltzera

a MPH, PhD, Grand Canyon University, University of Wisconsin-Madison Population Health Institute, USA

Objective: The objective of this qualitative pilot study was to identify opportunities and challenges Christian public health training programs experience when it comes to equipping public health students to work within Christian health mission organizations.

Methods: A sample of seven out of seventeen (41 percent response rate) primarily American Christian public health institutions completed an online survey. Thematic analysis was conducted to identify major themes in the following areas: values specific to a Christian worldview, competencies focused on integrating a Christian worldview, challenges to integrating a Christian worldview, and training available to students interested in Christian health missions.

Results: Values focused on Christ-like humility in serving God and others, discipleship, respecting human dignity in the image of God, and collaborative community partnership. More than half of the respondents identified the interrelationship between culture, religion, spirituality, and health as the primary competency integrating a Christian worldview. Global health was identified as the second competency followed by understanding the history and philosophy behind global health and missions. Identified challenges include faith of students and faculty, limited availability of Christian public health textbooks, and secularization of concepts such as poverty and development.

Conclusion: The holistic nature of public health is conducive to integrating a Christian worldview into program content. The results show that Christian public health institutions have biblical values and integrate a Christian worldview in understanding the interrelationship between culture, religion, spirituality, and health primarily through the lens of global health. Programs experience significant challenges to embedding a Christian perspective into other content areas. Opportunities for integrating competencies with a Christian worldview include offering a certificate in global health/development ministry, teaching methods for engaging individuals and groups in holistic health discussions, and incorporating spiritual metrics and instruments into program evaluation courses to measure the influence of faith, hope, and discipleship alongside physical and social health metrics.

Key Words: Public health, training, Christian, worldview, universities.

Christian health organizations, ministries, and churches leverage the discipline of public health to foster long-term improvements in community health.1,2 There is a growing recognition among donors and secular health and development organizations that faith-based organizations (FBOs) and local churches are critical to achieving and sustaining global development goals.2 Effective partnerships based on mutual respect and shared risk will become increasingly important as health disparities among the most vulnerable continue to grow. Secular organizations and donors appreciate the reach and trust faith-based communities bring to a partnership while providing funds and technical support to expand the services faith-based communities provide.3-5 It is important for faith communities and local churches to clearly define goals based on their role in the community as spiritual leaders. Faith-based organizations have the responsibility to recognize the foundation of spirituality in improving community health and integrate it into public health programs. Faith and spirituality are not supplemental but integral and central elements of health.

Partnerships with the public sector can artificially dichotomize the holistic nature of health and well-being into separate components of the physical and spiritual. Partnerships between FBOs and the public sector are important as communities move to increase their capacities to improve health. Benn recognizes that a critical part of these partnerships is the individuals responsible for facilitating the terms of agreement and expectations of each partner.6 He goes on to state that faith communities need to maintain their role as advocates and facilitators of inclusion in the community and not only be leveraged for their presence in the community as service providers.6 In the book, For the Love of God: Principles and Practice of Compassion in Missions, steps for developing a healthy partnership with the local church are described.7 Such partnerships require Christian public health leaders that can effectively communicate the mission of the faith-based entity to maintain its role in the community.

Given this understanding, it is important for Christian public health training programs to emphasize the spiritual determinants of health and to train public health practitioners to integrate these components effectively into such partnerships. O’Neill commented on the gap existing between the development and faith communities.8 This translates into a gap in the public health workforce and their understanding of Christian principles supporting FBOs effectively in secular partnerships. To address this gap, Christian public health institutions and programs will need to prepare students to have a common language that integrates public health and faith for effective communication, be accountable to the discipline of public health as well as the values of the local church, and build collaborative partnerships with the local church that prioritize the church’s perspective. Three competencies and skills to address this gap include stronger evidence of the role of spiritual beliefs and faith in development; understanding the perspectives of the practitioner, church, and community; and clear communication regarding the intended goals for effective change.8

Olivier also commented on the specific gap in academic programs in recognizing the importance of faith-based organizations and health centers in public health.9 She goes on to state there is a unique set of competencies required for faith-based health practitioners but limited opportunities to obtain this training.9 Most public health and development practitioners learn in the field and eventually come to a recognition of integral mission and participatory holistic health programming that values the process and relationship over short-term projects and interventions. The projects and interventions are important to achieve outcomes but only when conducted on a strong foundation of community trust and cohesion often established by the religious and faith-based institutions in the community.10 These elements of development are essential if sustainability and social justice are the long-term goals.

The Public Health as Mission initiative of the Global CHE Network consists of several Christian public health practitioners interested in understanding the role of public health in global health mission efforts (https://www.chenetwork.org/ publichealth.php). Christian public health training programs are uniquely equipped to train the next generation of public health leaders tasked with the responsibility of building effective partnerships. The purpose of this qualitative, pilot study was to understand how Christian public health training programs leverage their foundation on Christian beliefs and values to equip students with skills to strengthen public health ministry opportunities. A convenient sample of seventeen Christian public and community health training institutions were identified through personal communication and the Public Health as Mission initiative. A majority of the institutions (76 percent) were located in the United States and included large evangelical universities as well as smaller Christian colleges. Inclusion criteria included 1. A statement recognizing the institution as Christian; 2. Courses conducted in public or community health leading to a public health-related degree or certificate; 3. Contact information available through the institution’s website or network contacts. An electronic survey (see Appendix A) link was sent to one program leader (program director, lead, or faculty member) at each institution with one follow-up reminder email sent one week later. Fourteen institutions were based in the United States, three in Asia, and one in Africa. The response rate was 41 percent (N=7 completed responses) with six of the institutions based in the United States. The sample represented institutions from various denominations and ranged from small colleges to large universities. The survey involved the following domains: 1. Definition of public health; 2. Values that integrate a Christian worldview; 3. Program competencies that integrate a Christian worldview; 4. Challenges to integrating a Christian worldview; and 5. Christian short-term mission or service-learning training. Qualitative responses were coded and categorized by the author into themes to identify major themes in each domain. The term, Christian worldview, was not specifically defined in this study but is an area of important study as a person’s worldview influences the adoption of a particular development approach and process.11 Generally speaking, an individual’s worldview includes the set of beliefs and assumptions that guide one’s interaction with the physical environment and the supernatural world. A Christian worldview is based on creation, the fall of mankind, the reconciliation work of Christ, and mankind’s restoration with God. All content questions focused on program-level characteristics, and any contact information was provided voluntarily.

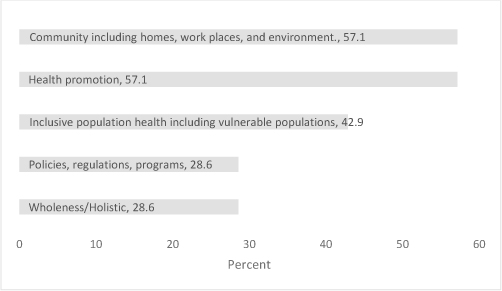

Among the institutions that responded, six offered a master’s degree, three offered a doctorate, two offered a bachelor’s degree, and one offered a certificate in public health. The themes in each domain were coded by the author. In some cases, a single response included more than one theme. An institution could contribute to each theme only once. Figure 1 shows the topics used in defining the term “public health” as applied in the specific programs. The top three themes focused on community (home, workplace, and the environment), health promotion, and inclusivity especially health disparities among vulnerable populations.

Figure 1. Themes in defining public health (percent; n=7)

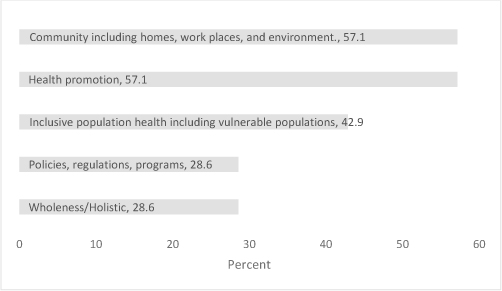

Figure 2 shows the second domain of program values that incorporate a Christian worldview. In general, the values cover three broad areas of loving God and others (humbly serving God and others), identity (human dignity in the image of God), and discipleship (faith, spirituality, character based on Christ). Humble service, especially for the disadvantaged, was the dominant value. Additional values included cultural competence leading to effective community engagement/partnership and approaching health holistically.

Figure 2. Program values that represent a Christian worldview (percent; n=7)

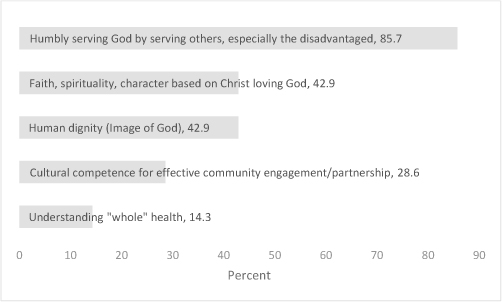

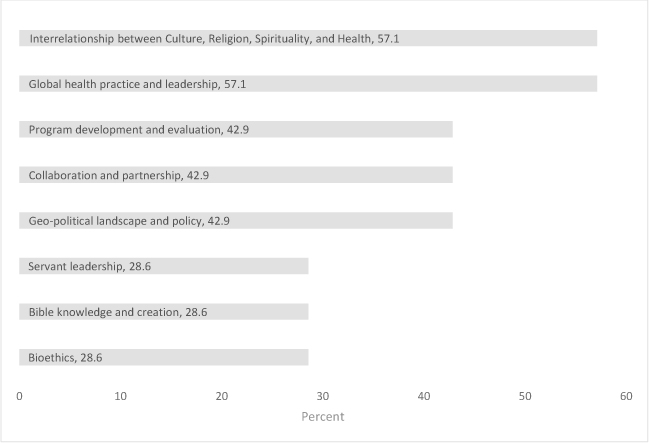

The third domain (Figure 3) of program competencies that integrate a Christian worldview gave institutions the opportunity to list five different competencies as well as corresponding assessment strategies. Each institution could contribute once to each theme even if multiple statements referenced that theme. More than half (57 percent) stated that understanding the interrelationship between culture, religion, spirituality, and health was a core competency. The same percentage also stated global health practice and leadership was a core competency that integrated a Christian worldview. Program development and evaluation were also mentioned that integrated a Christian worldview but details were not offered as to how this was done or assessed. Understanding a process for collaboration and partnership and the larger geopolitical landscape were highlighted as additional competencies that integrated a Christian worldview. This included understanding the history of Christian missions and how early health mission efforts influenced the current landscape of public health. Servant leadership and Bible knowledge regarding creation, the fall, reconciliation, and restoration undergirded the final theme of Christian bioethics as significant competencies that integrated a Christian worldview. The respondents did not provide specific assessment strategies for these competencies and is an area for future research.

Figure 3. Current program competencies that integrate a Christian worldview (percent; n=7)

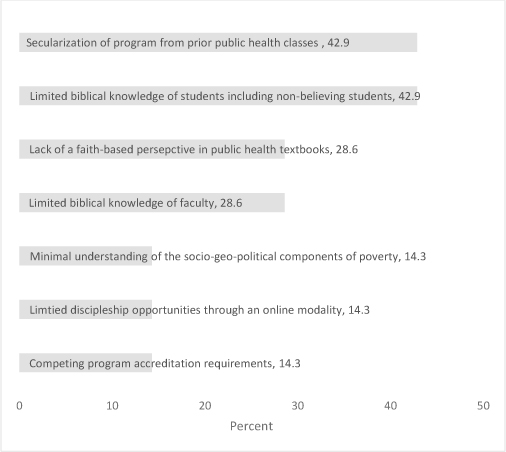

The fourth domain (Figure 4) identified challenges in integrating a Christian worldview into the program and curriculum. Institutions were able to identify up to three challenges. The first two challenges focused on the belief system of the students. Weak beliefs and faith of Christian students, as well as non-believing students, can lead to the secularization of programs based on previous public health courses and experience. This challenge can be compounded by the overall lack of public health textbooks that integrate and appreciate a faith-based perspective of public health. The faith of faculty was also identified as a challenge. Minimal understanding of the socio-geo-political definition of poverty, limited discipleship opportunities through an online modality, and competing program accreditation requirements were identified as additional challenges.

Figure 4. Challenges to integrating a Christian worldview into a public health curriculum (percent; n=7)

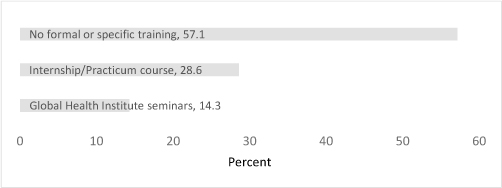

The final domain (Figure 5) asked about training requirements or opportunities offered by the institution for students interested in Christian health mission service learning experiences. More than half (57 percent) of the institutions did not offer formal or specific training for the students. Some offered opportunities through the internship or practicum experience, which could have included health mission models such as Community Health Evangelism. One institution identified global health seminars offered through the university’s global health institute as training opportunities but these were not required.

Figure 5. Training for Christian short-term mission trips or service learning (percent, n=7)

The purpose of the qualitative study was to answer the questions, “How do Christian public health programs integrate a Christian worldview to prepare students for global health mission service?” and “What challenges do they face integrating a Christian worldview?” Developing a strong Christian public health workforce that understands the importance of holistic or integral health through participatory community-church partnerships is essential to strengthen the impact of the local church in community health. Whole-person health and development require an appreciation for and knowledge about the psychosocial and spiritual in addition to the physical and environmental factors influencing health and wellbeing.12 Overall, the results show that the Christian public health training programs sampled appreciated the emphasis on community and holistic health when it came to defining public health. However, the relatively low priority of holistic health in defining public health represents a potential gap to strengthen the emphasis on whole-person care within public health training. Connecting these themes with the values highlights the importance of relationships as central for understanding poverty and health. Myers states, “The nature of poverty is fundamentally relational and its cause is fundamentally spiritual.”13 The relational includes our relationship with God, self, others, and creation. The values provide the scaffolding to hang the program competencies. Some of the competencies, such as program development and evaluation or understanding the geopolitical landscape, might not mention a Christian worldview but integrating a Christian worldview into these areas might be enhanced by adopting this definition of poverty. For example, including spiritual metrics and instruments in a program evaluation course could highlight the role of hope or other spiritual characteristics as key program components. Other competencies such as the interrelationship between culture, religion, spirituality, and health or servant leadership rely on a specific Christian worldview in that these require a biblical view of mankind and a belief that individuals are created with an internal desire for sustained holistic health and well-being.14 Understanding the interrelationship between culture, religion, spirituality, and health also requires a discussion of a specific object of faith. Relying on a false concept of spiritual or supernatural can cause harm just as a negative cultural practice can cause harm. Myers discusses observations of Jayakumar Christian in stating, “... powerlessness is reinforced by what he calls inadequacies in worldview. Writing within a Hindu context, Christian points to the disempowering idea of karma which teaches the poor that their current state is a just response to their former life.”13 Understanding the multiple determinants of health is necessary as well as how these determinants promote health rather than hinder it. Spirituality and religion tend to be recognized as important but rarely explored in a health curriculum given the diversity in beliefs and negative perceptions of “paternalistic and welfare” approaches historically used by churches.15 Public health practitioners working in Christian health and mission organizations play an important role in integrating the element of worldview while moving toward the centrality of the Christian worldview regarding holistic health. This necessity leads to some of the challenges identified by Christian public health training programs in integrating a Christian worldview.

Public health programs within Christian institutions include students from diverse beliefs. Teaching on the interrelationships of culture, religion, spirituality, and health requires sensitivity and an openness to respectful dialogue while upholding the importance of the Christian worldview. The public health content in many textbooks avoid discussing or even downplay the spiritual determinants of health. The strength of faith among students and faculty along with limited options for public health textbooks that teach from a Christian worldview create an opportunity to strengthen the connection between the values of Christian programs and public health competencies. Resources such as the Best Practices for Global Health Missions website (www.bpghm.org) provide a comprehensive toolbox of secular and faith-based best practices across multiple health topics to assist faculty members in integrating a Christian worldview with core public health competencies.

The results of the study identified specific areas for Christian public health training programs to improve the integration of a Christian worldview and how that worldview informed partnership development and holistic public health practice. The responses provided suggested opportunities (Box 1) to strengthen the integration of the Christian worldview and principles to equip students to effectively facilitate partnerships that honored the role of the faith community to holistically improve community health.

Box 1. Opportunities for training a Christian public health workforce

1. Provide a certificate in global missions within a public health program to strengthen the biblical knowledge and application among students interested in pursuing a career in Christian health ministry.

2. Include spiritual metrics and instruments as viable opportunities for evaluating the role of faith and spirituality in improving community health.

3. Encourage Christian public health faculty and graduate students to collaborate on writing textbooks that support a faith-based approach to public health.

4. Train for community engagement by modeling participatory tools for adult-based facilitation and teaching skills that are sensitive to communities with low literacy levels.

5. Offer a course, workshop, or seminar on biblical concepts that support holistic health as a practice and mindset. This could also provide the opportunity for students to engage with faculty members who have experience with cross-cultural faith-based public health programs and partnerships.

6. Engage Christian global health practitioners to share “friendship-based” or “life-based” case studies that represent the holistic side of public health alongside formal public health services and incorporate these case studies into a student-led seminar experience.

Limitations of this study included the small, convenient sample of institutions primarily based in the United States, limiting the power and generalizability of the results as they may not represent the larger population of Christian public or community health training programs in the United States or globally. Responses were coded by one individual leading to potential bias in the analysis. The strengths of the study included a satisfactory response rate of 41 percent with program types including certificate to doctorate programs. The survey maintained anonymity unless the respondent voluntarily shared contact information for future follow-up.

Christian public health training institutions include a Christian worldview in educating public health students but primarily do so through a global health focus. The gaps identified in this study offer opportunities for strengthening the integration of a Christian worldview into the curriculum of Christian public health training programs. Next steps could include conducting key informant interviews with public health program leaders and faculty to further identify assessment strategies for holistic health competencies throughout the program. Interviews could also address how public health programs are preparing students for emerging topics such as universal healthcare from a Christian perspective. Future research should investigate needs from global faith-based health and mission organizations in their capacity to employ public health practitioners as ministry workers and leaders thereby increasing the demand for such specialized training. There is an opportunity for Christian public health training programs and health organizations to identify competencies that equip students to integrate the spiritual determinants of health into holistic public health practice. Balancing a faith-based health organization or a local church’s evangelical mission with Christ-like compassion for people in the community is essential. Christian public health training programs are in a unique position to strengthen this mission workforce and provide professional development for those currently in the field in order to effectively initiate whole-person care and community health services.

Appendix A

Public Health as Mission – A survey to measure Christian characteristics and competencies within public Christian health training programs

Thank you for taking time to complete the survey regarding unique characteristics and competencies of Christian public health training programs. The purpose of this survey is to create a resource to support the development of public health competencies that integrate a Christian worldview and emphasize the role of public health in Christian missions, outreach, and evangelism. Your responses will remain confidential and results will be aggregated and compiled into a final report for dissemination. By volunteering to complete this survey, you are providing your consent to having your information included in the aggregated results. You can stop the survey at any time. If you have questions regarding any aspect of the survey, contact Dr. Jason Paltzer at jason.paltzer@gcu.edu.

Thank you in advance for contributing to this important movement in building on the strengths of public health to advance global health missions and ministry for God’s kingdom.

Dr. Jason Paltzer