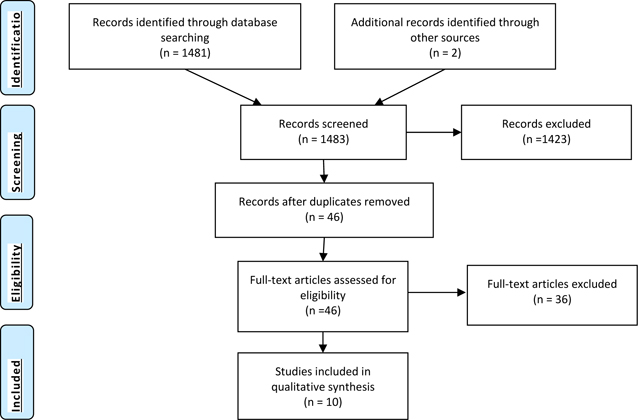

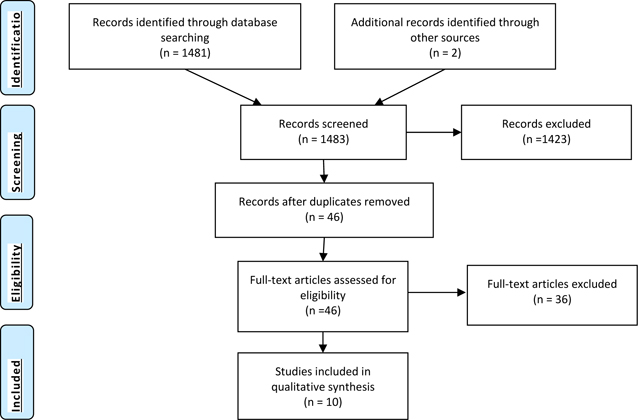

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram showing process of identifying records for Literature Review.15

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Andrew Wilsona

a BS, MD, University of Melbourne, Intern at Southwest Healthcare, Melbourne, Australia

Background: Faith beliefs, and associated cultural beliefs, play an important role in affecting responses to disability. There is no systematic review of how Hindu beliefs affect approaches to people with disabilities. The majority of the world’s Hindus live in India, as do a large number of people with disabilities. Therefore, this article seeks to explore the positive and negative ways that Hindu beliefs affect people with disabilities in India.

Methods: We undertook a scoping review of the available literature aiming to explore the barriers and enablers for people with disabilities provided by Hindu beliefs and practices. The databases PubMed, Scopus, and PsycInfo were systematically searched and several additional articles from other sources were included from searching the grey literature.

Results: Historically, the literature indicates that Indian, Hindu, karmic beliefs have advanced the view that people with disabilities are deserving of their condition. This literature suggests that this view continues into the present and can lead to stigmatisation of both people with disabilities and their families. In turn, this karmic understanding of disability can discourage people with disabilities from accessing medical treatment. Additionally, certain Hindu tribal remedies for disability may cause bodily harm and prevent the person with disability from receiving allopathic treatment. It was also documented that the attitude of Indian doctors toward people with disabilities are negatively affected by Hindu beliefs. One research study suggested that karmic beliefs can benefit families of people with disabilities by providing them with a context for suffering.

Conclusion: The study shows that Hindu religious belief effects, mostly negatively, the response to disability. This is important to consider when undertaking disability and inclusive development activities in India.

The Indian cultural landscape is dominated by religion, which significantly impacts the social perception of people with disabilities.1 According to the model of disability proposed by Wolfensberger, the services offered to people with disabilities in a community is dependent upon the underlying beliefs held by that community.2 This understanding is based upon the “social model” of disability.

Shakespeare notes that the social model of disability was originally outlined by the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS).3 In their foundational position statement, the UPIAS argued strongly that disability was caused by societal exclusion of people with impairments.4 In its purist form, this understanding means that disability is eliminated when society adapts to accommodate peoples’ impairments.4

This social model has been lauded by many academics as the catalyst for much beneficial change for people with disabilities throughout the world.3 Therefore, it is vital to understand the prevalent philosophies and attitudes toward people with a disability within the Indian society in order to understand their experiences and develop more effective strategies to benefit them.

This review will investigate how Hindu beliefs and practices affect people with disabilities in India. Although other religions are practiced within the Indian subcontinent, there are several reasons for focussing upon Hinduism. Firstly, Hinduism is the most influential religion in India. It is practiced by just under 80% of Indian nationals as identified in the 2011 Indian census.5 The historical traditions of Hinduism still exert considerable influence on the societal structure and culture of India today.6 For instance, the Hindu-based caste system has persisted in India despite being outlawed by the government, and Hindu notions of karma remain prevalent in modern Indian thought.7,8 Secondly, this literature review looks at Hinduism because the vast majority of existing work on the topic of faith and disability in India has focussed upon it, rather than other religions.

The situation of people with a disability in India has long been an issue of concern. In the 2011 census, 2.1% of Indians identified as having a disability, which Anees thinks to be a conservative estimate.9 People with disabilities in India are often illiterate and unemployed.5,9,10 Furthermore, they face frequent stigma and discrimination in many forms, often linked to prevalent community beliefs surrounding disability, as reported by Anees and Balasundaram.9,11 Stigma has been shown to negatively affect health outcomes by several processes, including social isolation and negative psychological responses from stigmatised individuals.12

Significant gaps in knowledge exist around understanding how Hindu beliefs and practices affect people with disabilities in India. A variety of studies have examined this topic in different localities, but they have not been synthesised and thematically analysed. Hence, this review aims to provide a broader understanding of the day-to-day effects of Hinduism in the lives of people with disabilities from across the nation of India.

This study investigates the causal explanations, benefits, barriers, and effects on treatment provided by Hindu beliefs and practices for people with disabilities in India. Beginning with some historical perspectives, it transitions into the current experience of people with disabilities. Finally, it considers how Hindu beliefs and practices map onto the established models of disability.

This piece is written as a scoping review. This was the most appropriate review form available for the topic, since most relevant articles were either observational studies or commentary pieces, which did not draw clear distinctions between culture and religion. Consequently, it was not possible to establish the rigid inclusion and exclusion criteria required for a systematic review. Therefore, this article is written as a scoping review which nevertheless utilises systematic methodology, where appropriate, to maximise its rigour.

The online databases Pubmed, Scopus, and PsycInfo were searched in February 2018 using keywords. The same keywords were used to search all databases. They were as follows: (disable* OR disabilit* OR handicap* OR retard*) AND (faith* OR religio* OR belief* OR superstit* OR spirit* OR Hindu* OR Jaini* OR Buddhi* OR Christian* OR Sikh* OR Moslem* OR Muslim* OR Islam* OR attitudes* OR karma*) AND (India* OR Hindu* OR Hindi*). Scopus and Pubmed were used because these databases provide especially broad coverage of the medical literature. PyschInfo was additionally utilised because it focusses on sociological pieces that may not be available in more classic medical databases. Given the relative paucity of papers available on the subject, the search terms were kept intentionally broad, aiming to find any papers related to people with disabilities and the Hindu faith.

For inclusion, papers were required to be written in English. Included papers discussed the impact of Hindu beliefs and practices on physical, intellectual, or sensory disability. Justification for the latter criterion is that some papers identified by the search strategy mentioned religion as a factor affecting disability, yet neglected to explain it in any depth, thereby providing insufficient material for discussion in this review. Hinduism was chosen as the religion of focus owing to its strong influence on modern Indian society and widespread coverage in the disability literature, as previously described.

With reference to WHO classifications of impairment, only studies focussed upon individuals with primary intellectual, aural, ocular, language, skeletal, visceral, generalised, or disfiguring impairments were included in this review.13 Articles that discussed participants with a combination of these impairments were also included. One key exception to this was articles that described people with memory impairment, which were excluded despite falling under the WHO category of intellectual impairment.13

A distinction was made between primary and secondary impairment on the basis that individuals with these impairments are viewed differently within the community. That is, a person with an acquired disability may have accrued significant social respect prior to the occurrence of their disability, as suggested by Anees.9 Conversely, a person with a congenital disability “may experience less hope and chance of attaining substantial education and opportunities for success due to the family, community and/or societal perceptions of disability.”9 Thus, persons with primary impairments were chosen as the topic of this study.

Studies discussing persons with psychological impairment were excluded from this review. Regarding conditions of the mind, the justification for differentiating “mental health” from intellectual disability is explained by the Intellectual Disability Rights Service.14 Additionally, dental studies were excluded. Two studies in which the researcher could not access the full text were also excluded.

Several other search strategies were employed in addition to database searches. Reference lists of articles identified via the database search were scanned for relevant articles missed in the search, yielding one resource. Additionally, a thesis was included in the literature review on the suggestion of one of the researcher’s supervisors.

During the database searching process, 1481 articles were identified. Additionally, 2 articles were identified by the researcher’s supervisors. These records were screened by title and abstract and 46 articles were identified as relevant. When the full texts of these articles were analysed, 36 were deemed not to meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 10 articles for inclusion in the study. This process is detailed below in Figure 1

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram showing process of identifying records for Literature Review.15

Of the studies included, six were commentary pieces, three were case studies, and one was a thesis. All included journal articles were peer-reviewed. Qualitative results are demonstrated below.

Religion is a difficult entity to define within the Indian context, yet it profoundly shapes the interpersonal relationships of Indian people, as Rao points out.1 He reports that Hinduism consists of innumerable writings compiled over thousands of years without a singular doctrinal focus. Despite this, there are consistent themes that shape Hindu thought, such as the concept of karma. Anees finds that the teaching of karma has important implications for people with disabilities.9

As alluded to, it is very difficult to pin down a concise definition of Hinduism, which has significant historical variation in its codification according to Rao.1 To further complicate matters, there are multiple sources from which the teachings of Hinduism have been drawn. For example, some strands of Hindu thought are pluralistic and incorporate teachings from other religions, while orthodox Hinduism only accepts teachings from the Vedic tradition. Furthermore, local Hindu teachings may be intermingled with superstitious beliefs, as described by Rao.1 Thus, it is almost impossible to form a concise definition of Hinduism.

Defining disability in India is also challenging, although not to the same extent as defining Hinduism. In Western thought, disability has traditionally been defined according to a medical model, whereby certain physical and/or mental impairments were deemed to render a person “disabled.” However, more recent understandings have focussed upon a “social model” of disability, which reframes disability as being a situation caused by social conditions.4 According to the UPIAS, disability may be addressed purely by reforming society to accommodate people with impairments.

Yet, neither models necessarily explain local perceptions of disability in India. For instance, Mehrota found that persons required to depend upon others were considered to have a disability in a rural Haryana community.16 For example, study participants questioned whether people with a hearing impairment had a disability since they could still carry out manual labour and were self-sufficient. This example is worth bearing in mind because it demonstrates that Indian people may have different understandings of disability to those adopted by scholars in the field.

Historically, the teachings of Hinduism have profoundly affected the treatment of people with disabilities in India, often in unhelpful ways. The concept of disability was frequently explained in Hinduism as being “sent by deity, fate [or] karma; often associated with parental or personal sin.”18 (p.57) Anees writes that people with disabilities are considered scheming and evil in Hindu writings.9 In one instance, the laws of Manu state that people with disabilities are suffering punishment for crimes which they allegedly committed in previous lives.18 It further states that they are “despised by the virtuous.”18 (p.57) Elsewhere, Miles found that the Laws of Manu prohibited people with various impairments from attending a sacred festival as they were thought to spoil it.19 He also notes that the Laws of Manu advised that people with disabilities should be avoided by other participants at the festival, to maintain ritual purity.

Another example of negative sentiment towards disability is found in the Hindu epic The Mahabharata. Anees recounts that in one story, King Dhritarashtra is made blind by the gods because in a previous life he had maliciously blinded a swan.9

Women with disabilities appear to have an even worse treatment than men in the Hindu scriptures, as Anees explains. Manthara, for example, is an ugly, evil, manipulative servant with a hunchback, described in the Ramayana. Like King Dhritarashtra, she had a disability, but unlike him she was not in a position of power. Similarly, Anees reports that the sister of the goddess Lakshmi was told by the god Vishnu that people with disabilities are not welcome in heaven. She was also made to marry a tree, which is clearly a humiliating experience.9

According to Rao, the Hindu concept of “Maya” can be applied to mean that all disability is an illusion of human perception.1 In essence, Maya teaches that the human cognition does not actually perceive reality, but rather an illusion. Furthermore, Rao writes that the real self is beyond human sensual perception in some streams of Hindu thought.

Drawing upon these ideas, Rao contends that Hindus could conceive disability to be an illusory human perception. For a Hindu, Rao believes that Maya could highlight “the real person behind the mere physical person receiving care.”1(p.132) Hence, he believes that Hindu carers of people with disabilities can take comfort that the actual self of someone with an impairment is not defined by their bodily limitations.

Yet this proposal seems overly optimistic. The documented real-world experience of Hindu carers of people with disabilities does not reflect or make mention of an illusory dimension to disability. Hindu carers in existing studies invariably acknowledge the reality of disability and then respond to it. An example of this is Khima, the Hindu mother of a child with a disability who sought help from numerous sources for her child’s condition.11 Therefore, Rao’s argument does not appear to have a solid basis in praxis.

On a more positive note, there is evidence that Hindu society occasionally made concessions for people with disabilities. Miles notes that efforts were made to include children with visual and speech defects during the Upanayana ceremony at the beginning of their education.19 This demonstrates some flexibility within the historical Hindu laws for people with disabilities, although their prospects for further education in this instance were “in most cases doubtful.”19 (p.256)

Certain laws were also made to prevent discrimination against people with disabilities, according to Miles.18 The Hindu ruler, Kautilya, and the aforementioned Laws of Manu contained a provision for the heads of families to care for relatives with a disability. Thus, it can be seen that Hindu teachings provide some benefit to people with disabilities.

The influence of Judeo-Christian ethics upon Hinduism during the colonial era aided certain marginalised Hindu societal groups, as recorded by Rao.1 He notes that the Christian imperative to love one’s neighbour profoundly influenced the teaching of the Hindu, Keshub Sen. In turn, Rao writes that Sen’s advocacy greatly improved the status of widows in Indian society. Although not directly applicable to the disability sphere, Rao argues that this humanist attitude, inspired by the teachings of Christ, may have contributed to the current focus upon providing service to people with disabilities in India. Expanding upon his argument, it is worth considering the potential of Judeo-Christian ethics to improve the status of people with disabilities in India today.

An example of Hindu beliefs being utilised to uplift the marginalised is possibly found in the teachings of Gandhi. Yet Rao notes that Gandhi himself was significantly influenced by Christian teachings. He reports that Gandhi saw a calling to love all people in both the Hindu Bhagavadgita and the Biblical Sermon on the Mount.1 To Gandhi, discrimination was not acceptable, according to Rao.1 For example, Gandhi strongly advocated for the rights of the “Untouchable” Hindu caste because he believed that their worth was equal to that of all other humans.1

Drawing upon this, Rao proposes that Gandhi would have treated people with disabilities with love and respect. He makes this argument as an extension of Gandhi’s humanitarian principles, noting that Gandhi did not explicitly mention people with disabilities in his teachings.1 Since Gandhi has been described as the “spiritual and practical leader of modern India,” it may be helpful for discussions on the rights of people with disabilities in India to make mention of his love for all humanity.1(p.187) Yet, despite the humanistic ideals of Sen and Gandhi, Rao notes that no major Hindu leader has directly addressed the issue of disability in India.1

Hindus frequently utilise karma as an explanatory means for the cause of disability, as noted by Anees.9 As Mehrota points out, karma states that “if one has committed misdeeds in [a past life], one has to inevitably bear the consequences.”16(p.37) According to Anees, disability is often seen as a punishment for previous sins. She mentions that these sins could have occurred in a previous life, according to Hindu teaching.9 Thus, people with a disability can be looked down upon by the general community for an unverified offence which cannot be proven.

Anees notes that an alternate Hindu explanation for disability is that a family member of the person with a disability had committed a sin. Needless to say, this creates significant stigma for both the person with a disability and their family, as found by Edwardraj.8 It is, of course, very difficult to defend oneself against the accusation of a sin committed in a previous life.

Gupta argues that the law of karma can bring hope to people with disabilities and their families. He states that karma may provide encouragement for people with disabilities to better their futures by doing good deeds.10 Therefore, by doing good deeds in the present, people with disabilities may have the hope of improving their social standing in their next incarnation, according to Gupta.

Yet, although the idea of hope being provided through karma sounds good, it is not evidenced in empirical studies. Karma provided no hope for the women in Balanadunsaram’s report of a multi-faith self-help group and was cited as a ground for social stigma by families of children with an intellectual disability in a study performed by Edrawrdraj.8,11

Interestingly, John found that a subset of parents denied that their child’s disability was a punishment for past sins and yet still held karma as a possible explanation for disability.20 This seeming contradiction may reflect the tension felt by Hindus with personal experience of disability about how to integrate their beliefs with their personal experience.

A related explanation for disability in Hindu thought is fatalism. There is some confusion over the nature of fate in the literature. Gupta defines fate as being ascribed to God’s actions, as opposed to karma which is a natural law that nonetheless may be modified by a deity.10 On the other hand, Mehrota found that Indians in rural Haryana viewed fate as an overarching, supreme reality that was determined in multiple ways, including via karma and through divine intervention.16 Owing to this confusion, it is difficult to ascribe the role of fate in the causation of disability in Hindu writings, except to say that it is generally considered a separate entity from karma and unable to be modified by an individual.

Fate and karma aside, several more peripheral explanations for disability emerged from literature. Mehrota found that various maternal behaviours were sometimes blamed for a child’s disability.16 For instance, her study reports that Hindus in rural Haryana sometimes viewed conception during a solar or lunar eclipse as a cause for limb deformity.16 Historically, Miles found that maternal behaviour was believed to cause disability in the writings of Caraka.19

A more sinister explanation for disability in Haryana was that wandering spirits caused limb deformities at the command of the local witchdoctor, as found by Mehrota.16 These peripheral beliefs are not derived from the Hindu texts, but they are nonetheless beliefs held by Hindus and illustrate what Rao labels as the pluralist viewpoint of many Hindu people.1

In a study investigating parental explanatory models for intellectual disability, John found that the majority of participants utilised religion as a coping resource.20 These parents viewed their child as a blessing from God. Additionally, they also believed that God would give them the strength to cope with any challenges arising from their child’s disability, as reported in the study.20 By doing this, the parents “[drew] strength from their faith,” thereby transforming the culturally unfavourable event of their child’s disability into a meaningful experience through which God gave them strength.20(p.301)

In another instance, Balasundaram found that religion benefitted parents of children with an intellectual disability who formed a self-help group.11 The group was organised by a Christian but consisted of women of multiple faiths, including Hinduism. In this group, the parents found comfort and solace together by articulating their spiritual quest for meaning in the context of their child’s disability. For these mothers, organised religion had provided scant comfort, yet spirituality had given meaning to their suffering, as reported by Balasundaram.11

For example, the Hindu mother, Khima, found support in the self-help group, but not in her Hindu beliefs, according to Balasundaram.11 Previously, Khima’s fervent prayers to Hindu gods and attempts to seek answers from Hindu religious leaders had been unsuccessful in either explaining or resolving her child’s disability. This led Khima to the conclusion that a god was punishing her for a sin, as Balasundaram notes. Yet throughout the course of attending the faith-based, self-help group and the meaningful connections she made there, Khima ultimately concluded that god had given her the strength to cope with her child’s disability. Therefore, according to Balasundaram, faith became a source of comfort for Khima, but not the practice of the Hindu religion.

Reflecting upon this story, it is reasonable to conclude that the interpersonal and spiritual connections made in the self-help group were the turning point in Khima’s faith journey. At this point, faith became an enabler in her life, whereas it had formerly been a barrier. This example, while only one person, demonstrates that the barriers resulting from Hindu beliefs and practices toward people with a disability can be overcome by the love and support of a faith community. Yet, Balasundaram does not make it clear in which faith Khima found comfort. It may have been Christianity, Hinduism, or a mixture of both.

There are also numerous instances in which Hindu beliefs and practices provide barriers for people with disabilities in India. Some of these barriers concern community and familial attitudes toward people with disabilities. Other barriers afforded by Hindu practices relate to the treatment options sought by the families of people with a disability.

Entire families frequently bear shame because of a family member’s disability within Hindu communities, as previously mentioned. Edwardraj reports that shame is frequently attached to the families of children with a disability in Hindu culture.8 He found that this is especially directed toward the mother of the family, who may be blamed for her child’s condition by her extended family. According to Gupta, such stigma may bring dishonour on the entire family within the wider community.10

These barriers are exemplified in a study by John of parental explanations for disability.20 In his study, a minority of participants believed that their child’s disability was due to karma or the wrath of God. John commented that these parents believed that “God had saddled them with a burdensome responsibility” in giving them a child with a disability. 20(p.304) When such an attitude is propagated from within the family, it is easy to imagine it also being propagated from outside sources who may have no personal experience of disability to inform their worldview.

People with disabilities may also be blamed for their impairments within the Indian medical community. Staples found that medical practitioners in Hyderabad generally thought that people with a disability had contributed to their own condition by being slow to seek medical treatment.17 Medical professionals studied explained the slow response of people with disabilities to seek treatment as being due to inadequate education and superstitious beliefs.

For example, Staples describes a neurosurgeon’s belief that Indian people with disabilities often place faith in sacrifices to gods and goddesses to cure them, instead of seeking medical treatment. In the neurosurgeon’s opinion, people with disabilities frequently sought these sacrifices in order to atone for past sins and appease the gods, as found by Staples.17

Likewise, lay people studied frequently described people with disabilities as “careless,” according to Staples.17 Thus, in a similar manner to health professionals, lay people unwittingly framed disability as a problem which must be fixed. They “deflect[ed] culpability for disabling conditions away from social institutions,” thereby removing the pressure from society to accommodate people with a disability.17(p.571)

Furthermore, Staples found that poorer members of the Indian disability community in Hyderabad frequently held simultaneous religious and medical explanations for disability. He points out that faith-based, causative beliefs for disability were sometimes held by poorer families, but not to the exclusion of Western medical explanations. In particular, he reports that the poorer people studied were more likely to take medical advice from a doctor than their wealthy counterparts.17

This was contrary to the opinion of the doctors in the study, who believed that people of low educational background held religious explanations for disability which prevented them from seeking medical treatment.17 Yet, as Staples17 notes, treatment is often inaccessible for the poor because they lack the funds for its implementation.

Drawing upon these findings, Staples believes that existing public health education in India is largely ineffective. That is, he reports an inverse relationship between level of education and reliance upon doctors to manage disability amongst study participants, who were primarily Hindu.17 When the poor did seek medical attention, they often lacked the financial resources for it to be effective. Hence, according to Staples, more public health education will not significantly alter the health-seeking behaviour of carers for families with disabilities in India.

Yet despite the evidence for Staple’s argument, it seems that public health initiatives could improve the lives of Hindus with disability. He appears to diagnose a flaw in the delivery of the public health message but fails to suggest ways in which it could be altered. For instance, education aimed at addressing the karmic explanations adopted by many Hindus could significantly reduce the stigma encountered by people with disabilities. By utilising culturally sensitive means to frame disability as a challenge that can be overcome, more families might view disability in the terms of the “Religious Resilience” category described by John.20(p.300)

Furthermore, it is important to note that Staples’ study was conducted in a predominantly Hindu city, but one in which there was also a significant portion of Muslims. As the study did not describe the religion of each participant, it cannot be assumed that all participants were of the Hindu religion, although the author indicates that the majority were. Of course, such a localised study does not represent every region of India or even a “typical” Hindu response pattern to disability and healthcare seeking practices. Thus, further work is needed in the field to develop the most effective strategies for utilising medicine to improve the lives of people with disabilities within the Hindu community.

There is a suggestion in the literature that Hindus are predisposed to avoid parental support groups. Specifically, Gupta states that Hindu people generally hide their suffering relative to disability.10 He argues that parents of children with disabilities may be less inclined to join parental support groups as this would make their personal needs known and may bring them shame from community members.10 However, this is a generalisation which the author does not back up with any empirical data. Hence, further research is required to validate this suggestion.

Drawing upon Balasundaram’s study, it is apparent that parental support groups are of great benefit to Hindu parents when they do join them.11 In light of this finding, parental health support groups could be a useful public health intervention to accommodate the practical and spiritual needs of Hindu parents of children with disabilities in India.

On another note, some interpretations of fatalism may prevent Indian families from seeking medical attention for their family members with disabilities. Mehrota writes that fate is viewed as an all-encompassing reality in Hindu thought, which is pre-determined for an individual but actuated by a number of different mechanisms. 16 Expanding upon this proposition, there may be a tendency amongst Hindus not to seek medical attention for people with a disability because their fate is considered sealed until they are reincarnated.

In some instances, Indian people with disabilities are brought to doctors when their condition has deteriorated beyond the reach of medical treatments, as found by Mehrota.16 Furthermore, she also reports that various treatments of unknown efficacy are utilised by traditional faith healers in India, which sometimes make an individual worse or can even cause disability via nerve damage.16 In some cases, this is due to Hindu beliefs that specific gods are responsible for certain ailments.16 These Hindus believe that it is necessary to appease the relevant god with offerings to cure the sickness, while giving traditional treatments to the patient.16 Mehrota notes that this may delay people with disabilities from being brought to the attention of allopathic practitioners until it is too late for treatment to be effective. Based upon this, a public health message which promotes early medical intervention in disability may be beneficial in certain rural Indian contexts.

It has been estimated that a large proportion of India’s population has a disability.9 Thus, both policy makers and healthcare workers need to understand how this large sector of the population is treated within Indian society. Unfortunately, culturally driven stigma and negative connotations associated with people with disabilities are prevalent norms in India today, as Anees, Mehrota, and Staples point out. 9,16,17

Since religion is “intertwined and immersed in the fabric of Indian society,” it is necessary to review the barriers and enablers that Hindu beliefs provide for people with disabilities in India. 9(p.32) It is hoped that a greater understanding of this situation will inform meaningful policy toward disability in India going forward.

Indian Hindu beliefs generally appear to favour a medical model of disability. Hindu society tends to view people with disabilities as having a problem which needs to be fixed, whether by means of medical treatment, traditional healers, or appeasement of the gods, as found by Mehrota, Anees, Edwardraj, and Miles. 16,9,8,18 This most closely resembles the medical model of disability, although local definitions of disability may differ from those established within Western medicine, as described by Mehrota.16

Hindu teaching also contains aspects of the charitable model of disability. The law of dharma stipulates the duty of the able-bodied to care for those with a disability, albeit for the purpose of accruing good karma for themselves, as found by Anees.9 Yet the fear and stigma that karmic beliefs attach to disability can somewhat negate this dharmic duty. This creates what Mehrota helpfully labels an “avoid-help” dilemma in Hindu society, in which Hindus are torn between their dharmic duty to help those less fortunate and an attitude that those with a disability are receiving a deserved punishment. 16(p.37) It is, thereby, possible that some aspect of Hindu beliefs assist disability work, whereas others are barriers.

This review is limited by the small number of studies published on the topic. This is probably because the topic is sensitive within the current political framework of India. More research is required into the barriers and enablers provided by Hindu beliefs and practices for people with disabilities in India. To date, research has been performed with small sample sizes at scattered locations throughout the nation, thereby limiting the generalisability of the findings. While the emergence of common themes in the literature suggests that there are similarities in the perception of disability throughout Indian Hindu communities, there are also specific local differences.

Furthermore, perceptions and health seeking behaviour can vary between Hindus of different caste and educational background. This also limits the scope of any conclusions drawn from this review. It is necessary to conduct more empirical studies in local Hindu communities throughout India to better understand how Hindu beliefs affect the response to disability.

Finally, the overwhelming diversity and fluidity of Hindu beliefs, which are not defined by a single doctrine or creed, makes their application to disability difficult. Yet it is important to gain a deeper understanding of this area to improve the standing of people with disabilities in India today.

In conclusion, this review has found some common themes concerning Hindu beliefs about disability in India. The most prominent and consistent themes include karmic beliefs for the cause of disability and the resultant stigma this attaches to people with disabilities in Hindu communities.

The information in this study is beneficial in numerous ways. Investigating the ways in which Hindu beliefs affect people with disabilities provides future direction for initiatives to promote their acceptance and societal integration. Additionally, it helps Indian healthcare workers to understand the experiences of their patients with a disability and to evaluate their own subconscious religious assumptions about disability. Policy makers should seek to better understand how a Hindu worldview affects the disability response in order to meaningfully implement the standards set in the Rights of the Persons with Disabilities Act (2016).21

Future empirical research on the beliefs and attitudes toward people with disabilities is required for other Indian religions, such as Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Sikhism. In particular, research at a community level needs to be performed to better understand the issues pertinent to specific areas of India.

This work is worth pursuing further. Challenging Hindu religious attitudes toward people with a disability will help Indian society to take meaningful steps forward toward their full inclusion.