Figure 1

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

John S. Lunna

a Vicar, Pastor, Grace Episcopal Church; Chaplain, Hospice Hawaii, United States of America

Years ago, the author was asked by a prominent palliative care leader if spiritual care could be conveyed in a ladder format as pain management had been by the World Health Organization (WHO). Many practitioners think about spiritual care as a way to identify and address spiritual distress. It is a way to address spiritual distress and so much more. In this article, an attempt has been made to depict spiritual care visually. Spiritual care providers and others will tell you that along with spiritual distress, there is also a powerful resource that spirituality provides. The spiritual care ladder endeavors to show both aspects, along with their relationship to one another and their inter-connectedness. This is not a resource for assessing spirituality; it is meant to help people better understand it and to visualize it so that the tools will be more helpful. Several valuable tools have been included in this article for the assessment of spirituality and faith components of a person’s life.

Key words: spiritual care, palliative care.

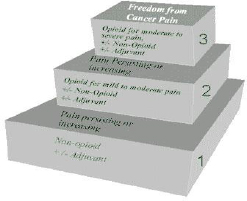

In 1986, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a three-step ladder (Figure 1) to help doctors and other medical professionals to picture and treat cancer pain in a simple and systematic way.1 This article will begin to develop a ladder to address spiritual care with this model in mind. The idea of creating a visual instrument for the spiritual component is both intriguing and intimidating. The typical three step ladder, which is used around the world for physical pain management, has worked well as an image for understanding pain levels and interventions. A spiritual care graphic will require a different kind of look to better appreciate the interplay involved. We may start with spiritual issues and problems, but then we need to find space for another attribute.

Spiritual care is also about making use of one’s deepest resources to cope with and deal with the challenges of life, including that of a terminal illness—of impending loss. So, could we think about three steps up and three steps down? One set of three represents the spiritual resources and the spiritual foundation of our lives, and the other set of three represents the challenges and/or pain that can result from that foundation being shaken/threatened. Which one is up and which one goes down? How can we see the integral relationship between them?

The steps are meant to be a guide that helps us connect to or engage with a person’s story. We start where the patient is when we encounter them. The pain relief ladder uses a predominately pharmacologic approach. If the pain is moderate, then we try this, this, and then this. A spiritual care model will look at the physical, the psychosocial, and spiritual aspects as interdependent. Culture, community, and family will impact the situation and the outcome.

The model offered here will have a Christian leaning. It can also be used as a basic model, with slight adaptation, with any faith group or even with someone who is “spiritual, but not religious.” (Arguably it could be used with an atheist as well.) The basic concepts are universal, whereas the supporting examples will mainly come from one tradition (in this case, Christian).

The model that will be used here is known as the Penrose stair2 (or what MC Escher called “Ascending and Descending”) as our representation of the spiritual care ladder. Roger Penrose, its creator, and MC Escher, an artist who developed it, spoke of it representing the “impossible”—a stairway that perpetually ascends or descends. By utilizing such a model, we can more easily visualize the three steps of faith or belief that act as spiritual foundations. We can also visualize spiritual issues and challenges, and see their ultimate connection, their basic relationship. The Apostle Paul suggests a similar idea in relation to the Christian hope when he tells us in Romans 5:3-4 (NRSV)3, “We also boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope.” There is a paradoxical (or we could say impossible or at least puzzling) relationship between faith and doubt, strength and weakness.

Let us begin with the three steps of faith or belief. Here, we travel not so much to the height as to the depth of that faith/belief as we move from 1 to 2 to 3. It could look something like this (Figure 2):

In the first step—Meaningful practice/ritual—we could include prayer, sacraments (baptism, communion, and anointing), worship, scriptures, readings, religious services, and devotional time. One could also add many more.

The second step—Practical beliefs—might include confession and forgiveness, expressing and accepting love, trust in God’s grace and love (Romans 8.28: “We know that all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to his purpose.”)

In the third step—Core/foundational beliefs—things like God is love, God is just, God is omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent (“knows all things,” “all powerful,” and “present everywhere”) and the belief in grace, hope, love, and faith might be included.

These three steps are interconnected. The strength of that connection will depend on the foundation—on step three. Here, we are reminded of Jesus’ parable about the two houses—one built on rock and one built on sand. Ritual, practice, and practical beliefs will withstand the “storms” of life if they have a solid foundation at their core. It does not mean that they will not be shaken or tested, but they will remain. If the core is poor, the steps might not withstand the storm, and a true “crisis of faith” may result. The good news for Christians is that God can change that sandy foundation into stone; we will examine this further as we look at how, as Paul suggests in Romans 5, “suffering produces… hope.”

Now, let us look at the three steps of spiritual issues, challenges, and problems. (Figure 3) As seen in step one — the initial question is most often “Why?” or “Why me?”

The first step is “Why? Why me?” As we begin to face the reality that we have a life-threatening illness and may die soon, we often start to wonder why it is happening to us. This is human; this is normal. This is a question that cannot be answered by someone else. It is a question that invites us to explore our depths. At this step, the primary intervention on the caregiver’s part is “listening.” The philosopher Epictetus said, “We have two ears and one mouth so that we can listen twice as much as we speak.”4 Here, our words should be sparse—used to help the person clarify their question and maybe remind them of the resources that are at hand. This may include scripture, other inspirational books, music, and the arts. For many, the end result of this questioning is shifting to a new question—one like “What now?

The second step is “God has abandoned me.” This could be seen as one of the answers to the “why” question—“This has happened because God has abandoned me.” For some reason, this inner questioning has not provided a satisfactory or acceptable answer; it has not come up with a new direction or question to follow. Again, the primary intervention on the caregiver’s part is “listening.” This may be the time to refer to a spiritual care counselor or other counselor. They will explore the feelings behind this sense of abandonment and will try to help the person move in the direction of “What now?”

The third step is “There is no God.” or “I am alone.” This comes from the depth of the soul, a place that, for the moment, feels empty and vacant. St. John of the Cross, a 16th century Carmelite, referred to this kind of experience as the “dark night of the soul.”5 Can we get to this place if we have a solid foundation? Of course we can. Jesus asked this question from the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46b) Jesus was in this place on the cross. This can be a place of growth, a place where we explore what we can trust, who we can trust, and what is actually meaningful and, therefore, consequential in our lives. “Listening” remains the primary intervention, but this listening may need to be by a “trained listener” (e.g., Palliative Care/Hospice Chaplain, Spiritual Director). This place requires work and sorting out. It is a time of soul searching—deep and often painful soul searching. Henri Nouwen suggests the following:

But what I would like to say is that the spiritual life is a life in which you gradually learn to listen to a voice that says something else, that says, “You are the beloved and on you my favor rests.” I want you to hear that voice. It is not a very loud voice because it is an intimate voice. It comes from a very deep place. It is soft and gentle. I want you to gradually hear that voice. We both have to hear that voice and to claim for ourselves that that voice speaks the truth, our truth. It tells us who we are. That is where the spiritual life starts — by claiming the voice that calls us the beloved.6

In I Kings 19:11b-12, we read of Elijah meeting God. “Now there was a great wind, so strong that it was splitting mountains and breaking rocks in pieces before the LORD, but the LORD was not in the wind; and after the wind an earthquake, but the LORD was not in the earthquake; and after the earthquake a fire, but the LORD was not in the fire; and after the fire a sound of sheer silence.” In the KJV we read, “a still small voice.”

One struggle with the model is where to place steps 1 and 3 on the model. An argument can be made for either placement—at the top or the bottom. There is a mysterious connection between the challenges that we face and the source of grace, hope, love, and faith in our lives. It is in this space that we profoundly encounter God. In the Penrose stair, this space has been highlighted between the two sets of three steps.

In its depth (shown in purple/dark shading), there is a connection between the challenges we experience and our core beliefs. (Figure 4) Those core beliefs provide a foundation from which doubt, questioning, and anger can be encountered. Ultimately, this is where growth is possible. It is in this space that spiritual transformation takes place. I hearken back to Paul in Romans 5:3-4 “… we also boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope.” This is one way to understand that “back stairway” between our sufferings and our strengths. It is where suffering comes to be hope, where beliefs connect with experience.

Some people may find the image of the biological process of metamorphosis more helpful. Here an egg becomes a caterpillar becomes a chrysalis becomes a butterfly, changing from one stage to the next. In the biological metamorphosis, the progression seems foreseeable. In a spiritual metamorphosis, that path is far less predictable. There are so many variables, some understood, many not.

It seems a contradiction, but many of our core beliefs have their beginning in such encounters with doubt, questioning, and anger. Friedrich Nietzsche said, “That which does not kill us makes us stronger.”7 Viktor Frankl said, “Live as if you were living a second time, and as though you had acted wrongly the first time.”8

Here are a few other thoughts in relation to this concept:

Doubt isn’t the opposite of faith; it is an

element of faith. - Paul Tillich

God always answers in the deeps, never in

the shallows of our soul. - Anonymous9

And from the scripture, “Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” (Hebrews 11:1)

[Fr. Mark Stelzer suggests taking] a different approach with our pain. What if instead of running from our pain, we paid attention to it? What if we listened to our pain “to know what God is saying to us?” What if we acknowledged that our pain, whatever its source, is not the final word? What if we trusted that even in the midst of our pain, God loves us and is working in us?10

When we talk about pain management from the ladder, we also acknowledge five essential concepts in the WHO approach to drug therapy of cancer pain. I want to put them alongside five essential concepts to spiritual care (Table 1):

| Pain Relief Ladder (WHO)11 | Spiritual Care |

|---|---|

| By the mouth | By the ear – listen with a non-judgmental and open presence. |

| By the clock | Throw out the clock. People need time. Offer regularly |

| By the ladder | By the Penrose stairs |

| For the individual | For the individual in the context of their community. (Each person’s experience is unique.) |

| With attention to detail | With attention to strengths and resources |

Spiritual listening is the key concept here. This listening can be aided by practice in this type of listening, reading, and study of various spiritual practices, tenets, and beliefs. It is important to have self-awareness, that is, being aware of what is important to you and your spiritual journey and/or practice.

In palliative care, as in other areas of medicine, there are many different assessment tools. An early contribution to assessing the spiritual component was made by Christina Puchalski, George Washington University, when she developed a questionnaire that she used to teach health care professionals how to obtain a spiritual history. The acronym she used is FICA:

This tool allows the health care provider to explore the spiritual aspect of a patient’s life and receive from the patient their desire for utilizing these resources through the assistance of the health care team. This is something that may need to be revisited from time to time to see if the person feels the same way about accessing these means.

Another tool, developed for medical doctors, is the HOPE Questions for a formal spiritual assessment (Table 2) in a medical interview. This was developed by Gowri Anandarajah and Ellen Hight of Brown University.13 This tool helps identify spiritual resources that a patient could potentially access. The HOPE Questions offer the person being interviewed an opportunity to comprehend what the questioner is trying to explore. This series of questions may work better with a person coming from a “traditional” faith group, e.g., Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, etc.

Since simple is often a good place to start, let us look at the three questions developed by Carolyn Kinney to assist a nurse in assessing the spiritual aspect of a patient’s care. With practice, these three questions become the basis of an in-depth conversation about one’s spiritual nature, the foundation and the spiritual challenges. Because Kinney’s three questions are more open-ended they may prompt a person to answer with less traditional or conventional answers. In time, the questions can take on one’s personal flavor or character.

These questions are meant to start a conversation, a conversation that is mostly listening on our part. These are open-ended questions where the “right answer” is their answer. It gives an opening, an opportunity for the person to explore these important areas of spirituality, of life.

These questions, put in a language that may feel more natural for you, are basically an invitation. They are an invitation for that person to feel they are free to share their intimate struggles and burdens, and even their doubts with us. It is like saying, “You can talk to me. I’m a safe person with whom you can share your feelings.” Be sure that you are a safe person, a non-judgmental and open presence, before making the offer. You may hear things that shock and distress you. Your disapproval, displeasure, or condemnation will not be helpful here. In Jesus’ ministry, He allowed people to come to Him as they were and for whom they were. (Sinner, tax collector, demon possessed, Samaritan, Canaanite, leper, or someone of questionable character.) He helped them make the changes they desired.

The doctor tells us that we have cancer and only a few months to live. What do we make of Jesus saying, “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly,” (John 10:10b) in relation to that? Do I understand this as a mistake made by the doctor? Or, can this be seen as an invitation to live out my life fully and discover a richness in life I may not know? Those working with people with terminal illnesses do see this response. Brian White says, “It’s not the days in your life, but the life in your days that counts.”15 Also, we are reminded that, “Life is not measured by the number of breaths we take, but by the moments that take our breath away.” (Anonymous16)

Our deepest beliefs can offer suffering a context, meaning, and transcendence. Viktor Frankl, a psychiatrist and survivor of the Holocaust, offers the following story of a client:

A doctor whose wife had died, mourned her terribly. Frankl asked him, “If you had died first, what would it have been like for her?” The doctor answered that it would have been incredibly difficult for her. Frankl then pointed out that, by her dying first, she had been spared that suffering, but that now he had to pay the price by surviving and mourning her. In other words, grief is the price we pay for love. For the doctor, this thought gave his wife’s death and his own pain meaning, which in turn allowed him to deal with it. His suffering becomes something more: With meaning, suffering can be endured with dignity.17

With meaning—with someone (not feeling abandoned or all alone)—with a positive outcome, the worst things of life can be endured and even act as positive, life-changing experiences. Once again, we are reminded that “We know that all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to his purpose.”(Romans 8.28)

In his 2003 IJPC article, Coping with terminal illness: a spiritual perspective, Sanjeev Vasudevan puts forward the concept of transcendence. Here he suggests that “transcendence can be described as a movement of the mind from the material plane, so full of pain and suffering, into a non-material plane.”18 That movement is spiritual liberation. It should be noted that transcendence is a notion that spans many religious traditions and philosophies.

Vasudevan also suggests that we must have an awareness of our own spirituality, not to offer as a solution or answer, but rather as a foundation for this often-difficult work. Further, in this endeavor, we continually learn and grow from what our patients teach us.

Life itself is a spiritual journey. It is a journey where our responses to challenges and happenstances serve as the building blocks for our resources and abilities to cope with and endure those things we encounter in life. This process, or course, is shaped by our faith, our community, and our spiritual and religious teaching. When we face our own mortality, this spiritual journey is quickened, it is accelerated. This spiritual care model is designed to help us understand how one can explore and encounter the spiritual issues, challenges, and problems from the platform which is created by summoning the depths of our own faith and/or belief. It is descriptive rather than prescriptive. It is conceptualized instead of substantiated

In the future, I hope to flesh out assessment tools that would work within this framework. I would encourage others from various backgrounds, traditions, and settings to engage with this model and see what tools, techniques, and methods surface.