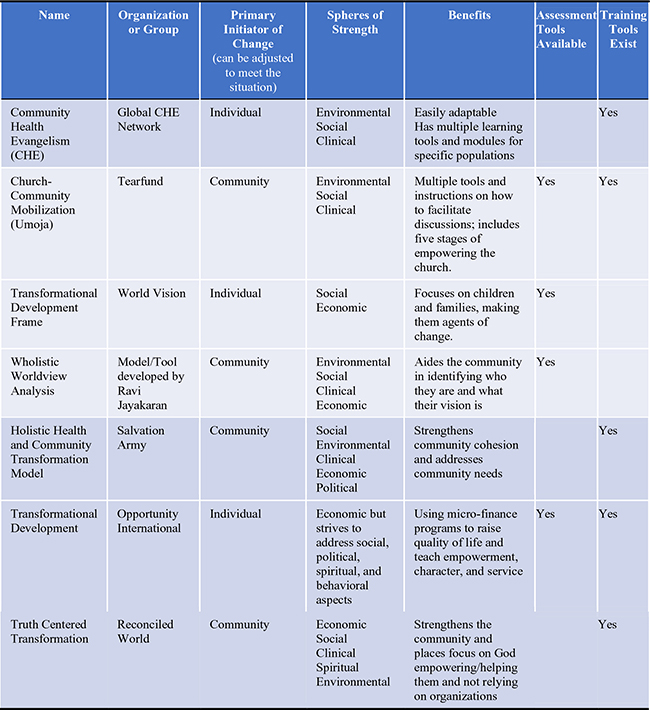

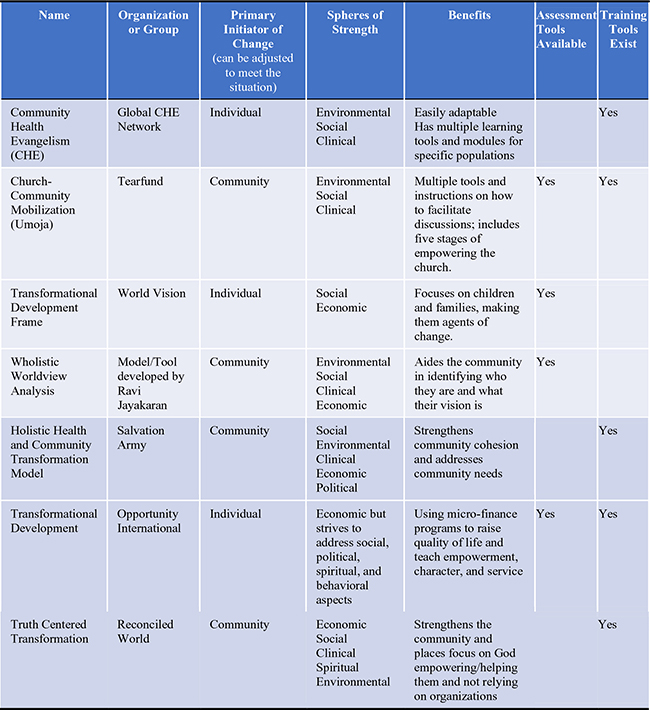

Figure 1. Comparison table of predominant holistic models

REVIEW ARTICLE

a Student, Grand Canyon University, United Sates of America

b PhD, MPH, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology, Department of Public Health, Baylor University, United States of America

This review identified and determined core aspects of holistic health models often used in faith-based global development to integrate the spiritual determinant of health into a multiple determinants framework. Understanding the similarities and differences of such models is essential when planning development opportunities. Seven holistic health models were identified for review. A similar feature among the models was the importance of the community’s worldview and health beliefs on discussing the spiritual aspects of health and behavior change. Community engagement and cultivating relationships were two common themes motivating the models. A primary difference among the models was the direction of engagement. Some models intentionally focus on individual-level relationships and move toward larger community-level impact while others start at the community-level and move toward individual-level engagement. Both approaches are helpful depending on the context, community readiness, and available local leadership. Based on the review, two diagrams or maps were created to help organizations determine which models or model components may be applicable to their situation.

The relationship between faith-based organizations and community health and development has been the topic of much discussion within the past twenty years with focus on how a holistic model can lead to a more successful and sustainable outcome.1,2,3 Holistic health can be difficult to define and even more difficult to apply in practice.4 Public health and religion have at times been at odds with each other resulting in distrust and limited collaboration for the benefit of the community.5 Given this history, communities of faith and public health agencies have successfully worked together to improve health in faith-based partnerships.6 This history provides the significance for reviewing existing approaches not only to work together but to authentically combine faith with public health. Faith-based health organizations often describe an integrated approach combining the physical and spiritual determinants of health in various community health programs. However, this integration can range from staff with spiritual beliefs implementing health services, to a brief devotion or prayer prior to delivering services, to embedding scripture lessons into the service delivery. Faith-based holistic health models have been developed to assist organizations looking to emphasize the spiritual determinant of health alongside and within the physical, social, and emotional determinants when it comes to improving quality of life. Such models contain several assumptions: 1) faith and beliefs drive behavior; 2) faith and beliefs determine the strength of relationships; and 3) faith and beliefs influence priorities. From these assumptions, holistic health models start from a place of faith to inform the other health determinants.

In order to further understand what a holistic model is, it is necessary to explore the definition of poverty. A typical explanation of poverty is simply a lack of resources, but when examined with a different lens, it is possible to see how authentic holistic community health and development can lead to communities that thrive. A biblical view of poverty can be defined in terms of relationships.7 When sin entered the world, it broke mankind’s relationship with God, each other, and the environment, creating a fractured system. Holism has at its core a focus on the restoration of these relationships. A holistic health model, therefore, seeks to complement existing health services by improving the relationships and addressing the conflicts hindering the living conditions and environment. It also promotes health and works toward removing obstacles to freedom, while keeping a relationship with God at the center. This differs from a secular multidimensional approach to community health and development, which takes into account various aspects of life such as genetics, environment, culture, or health beliefs but not necessarily on a foundation of faith and spirituality.8

It is important to understand this difference between a faith-based holistic model and a more secular multidimensional approach to development. Within the world of multiple determinants of health, models exist that include components impacting a person’s health like the physical environment, genetics, and the social environment, but spirituality is minimally addressed or absent from discussions of “holistic” interventions. The Health Field framework,9 the Social-Ecological Model,10 and the One Health model11 are three examples of multiple determinant models that imply spirituality as a determinant but do not consider it as an integral aspect of health. For the purpose of this review, a holistic health model was defined as one that integrated faith and a belief system in other dimensions of health. This integration is important and is what sets holistic health and development models apart from secular models.

Within the current literature, there exists some gaps in knowledge regarding how holistic health models are implemented, where they are implemented, and whether models of holistic community development vary or are similar.1 A common criticism of faith-specific holistic health models is that they are not always sensitive to or inclusive of traditional or local beliefs and how these beliefs interact with the overall health of the community. It can be easy for organizations to go into a community with a heavy focus on their definition of what faith is or should be and not address the existing belief structures. Given this real possibility, it is important to explore various health models and determine strengths and limitations of each model to minimize division given the existing faith and belief system of each community.

A successful holistic model will be able to address the community’s existing spiritual beliefs and either use them as motivators for health or introduce the community to a new way of thinking to promote health and development through reframing, reprioritizing, and reforming beliefs.12 While a holistic methodology can be undertaken by a faith-based organization from any religion,13,14 the majority of the literature reviewed for this paper involved Christian faith-based organizations integrating a Christian worldview and beliefs. Although much literature exists describing examples of faith-based community health and development endeavors, the majority are focused on efforts in Africa15,16,17 and Southeast Asia.13,14 Individual models are identified, such as Community Health Evangelism18 and Umoja,19 but little to no comparison of the models exists. This lack of side-by-side evaluation leads to a need to examine the various components and driving factors behind the models. Such components include how the model engages the community, how it incorporates and measures spirituality (both the community’s existing spirituality and that of the faith-based organization) and health, and its view of holism as a primary approach to the development mission or as a secondary priority.

Evaluating the strategies behind holistic health models is an important factor that should be undertaken before implementation of any project. Currently, no decision matrix is available to help choose what holistic model may be appropriate for the community. This paper will focus on providing a comparison of the components of various holistic models of community health and development and identify tools used to evaluate the community throughout the development process. The goal is to provide a starting point for developing a resource with which to determine how to select a holistic model that fits the community of interest or pull together components of multiple models. This will also help in measuring effectiveness of the models by identifying unique components important for the change process.

A review of the existing literature on transformational or holistic community health and development was conducted from September 2018 to January 2019 to identify existing frameworks or models being used within the community development field. The following databases were used: SciELO, Directory of Open Access Journals, ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials, Social Sciences Citation Index, Academic Search Complete, ScienceDirect, CINAHL Complete, and JSTOR Journals. Key words and search terms used to identify articles focused on combinations of community or transformational development, faith-based development, wholistic framework for development, integral mission, holistic mission, and model of community development. Search results yielded almost 2,000 articles. From these results, special attention was given to those articles with a more holistic community development focus which could include addressing issues like clean water and agriculture which impact health rather than on those that dealt with individual diseases. Approximately 250 abstracts were read, and of these, 120 were chosen for in depth review. Evaluation of whether the model presented was truly holistic or simply multidimensional further refined the study. Articles discussing other helpful processes and methods and one-off programs that demonstrated integration and discipleship like the Salvation Army diffusion model15 and Missao Integral20 were excluded from discussion in this paper due to their lack of an organized developmental focus. Resources pertaining to these methods are included in the annotated bibliography available upon request. The review focused mainly on international development as this was a trend in the majority of the literature; however, some models were discussed within the context of the United States. Users of the models were contacted by email to provide input into the categorization of their models. Input from those that responded were taken into consideration during the categorization process.

The existing literature and resources that were reviewed contained many different models of holistic development. Figure 1 provides a list of the selected models reviewed and key components identified from the literature. Some models did not have extensive support in the literature and may have components or characteristics not described in this review. During the review, it was helpful to group the frameworks, tools, and networks according to their similarities and differences alongside their specific strengths.

Tools like the Wholistic Worldview Analysis with the Ten Seed Technique21 as well as CCM-Umoja with the Light Wheel22 allow for the community to categorize and measure their concerns, evaluate the agents that are causing the concerns, and then, as a whole, determine their priorities. These tools can serve to measure the community’s starting point and create a baseline against which to evaluate future community growth throughout the development process. Other models like the Holistic Health and Community Transformation Model and Community Health Evangelism (CHE) utilize health flip books as a method of explaining health ideas in an easy to grasp way.15,23 Community guidebooks and modules for the community to work through on specific topics also exist and are used by multiple models including Truth Centered Transformation. For example, a module may focus on women and children’s issues, economic development, or agricultural skills. Assessment tools that can be used before, during, and after the community transformation also exist for the majority of the models reviewed.

Figure 1. Comparison table of predominant holistic models

Although spiritual measures were identified as being important to measure, these specific measurements were not clearly defined and is an area for continued improvement. After implementation, the impact of holistic development was measured in three core areas: physical health, spiritual life, and community cohesion (Figure 2). A community going through holistic development will also have spiritual change. Holistic models emphasize the soul and foster a relationship with God as foundational for understanding purpose and identity. Spiritual life can be measured through local church activity or the influence of faith in daily decision-making and behavior. For a truly holistic model, restoring a relationship with God is central7,20,24 as it determines the motivation for serving the larger community beyond the individual, a necessary component of development. Improved community health can also be measured by direct interventions like vaccines, improved water/sanitation, and adequate nutrition. Decreases in disease incidence, morbidity, and premature mortality are indicators of improved physical health.25 Community cohesion and the extent to which the holistic approach brought the community closer together is a third type of measurement used by models to measure growth. Sharing of resources and skills, social trust, and a greater sense of service can be measures of community cohesion.25 Reviewing the models together emphasizes the importance of measuring impact across these three areas throughout the development process and be used to determine how closely the community is staying accountable to its set priorities.

Figure 2. Measurement indicators

The holistic models discovered during the review are similar in a few key ways. First, community “ownership” is an essential part of all successful development and is no exception when it comes to holistic health models.23,26 Ownership typically starts with the community defining what strengths, assets, issues, or needs exist and deciding on possible solutions. Holistic models may differ in the approach, processes, or tools used to get to the decision because they start with the community’s worldview. This leads to a focus on motivation and purpose for addressing change. Basing ownership on this deeper sense of purpose rather than general input or advice takes more time but is also more sustainable as it switches the typical decision-making paradigm. The facilitating organization provides input but the community members have ultimate decision-making ability regarding development and use of their existing skills and resources used alongside any requested training or resources. Maintaining the dignity of the community members is central in a self-sustainable community. Holistic health models differ regarding community ownership by emphasizing a deeper sense of purpose through faith in God and this manifests itself in communal unity through service and volunteerism. As change happens in the individual, there is a desire to help others find the same freedom. This is achieved in part through service. A model’s sphere of strength can be used to help identify an appropriate model depending on the community’s worldview, assets, and needs.

A second similarity between the models is the practice of multiplicative capacity building or a training-the-trainer approach to learning. In many communities, this is used to strengthen community cohesion by building trust.18,23,26 Often times, an organization is embraced if a trusting relationship between members of the community and the development organization exists. An example of this concept is seen in the work of Dr. Regi George and Dr. Lalitha Regi who created the Tribal Health Initiative in the remote villages of India. As doctors, they were able to train community members to be community health workers who could then provide maternal and child care.14 Building trust took a while, but eventually the whole community came to embrace the new health workers. Community and health development training can take many forms, from medical training conferences27 to agricultural skills.16

A key difference among the models is in the flow or direction in transforming a community. Some start with individual change and then spread to community as seen in CHE and World Vision models23,28 while others start with the community and then trickle down to individuals as seen in Tearfund’s CCM-Umoja model.19,29 Each approach has its strengths based on the existing community politics, attitudes toward religion, and issues facing the community. Whether a model starts with individual change or community level change can depend on the context of each site in which they are working. Some of the models are adaptable and can operate at both levels simultaneously. For the purpose of this paper, we assessed them on the approach most often represented in the literature.

Some models, like Opportunity International’s transformational development, touch on specific determinants of health such as agriculture or economic development;25 others are more diverse and have manuals or resources that address a wide range of determinants including women’s health, sanitation, and education. Another difference is how faith and worldview are integrated into the development process. Some models specifically integrate scripture lessons into the training or lessons such as the CHE model, while others rely on the tool connected with the skill of the facilitator to integrate faith into the community discussions such as the Wholistic Worldview Analysis.

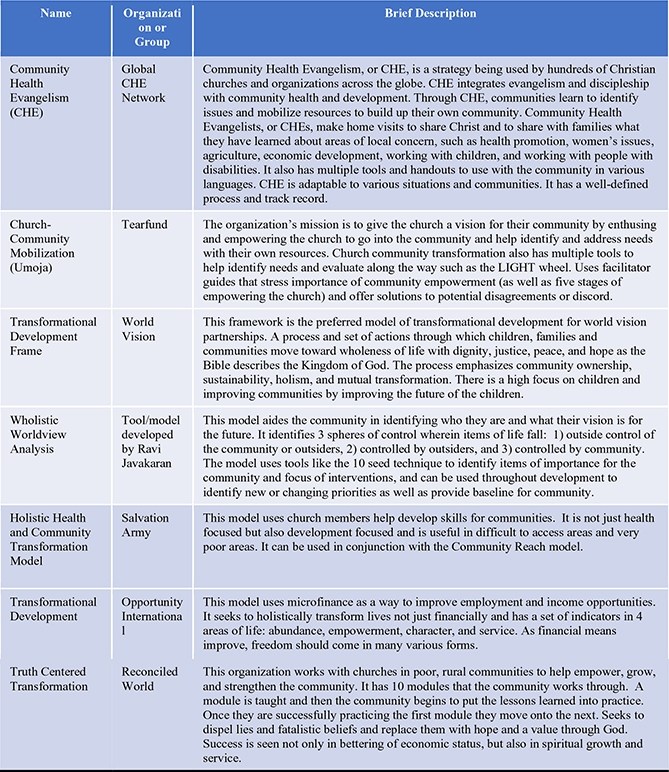

The goal of this review was to evaluate the current models of holistic health and create a model map that would help communities and organizations determine which model might be best to use based on the specific needs of the community. During this research, several large models were identified and a summary of each is included in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Table of model summaries

Each community comes with its own challenges and pre-existing foundational resources. Among the literature identifying holistic community health models, there are a few overarching themes that need to be addressed when looking to adapt the model to future communities. Two themes guide the start of the process: individual versus the community and the availability of churches or spiritual leaders in the community. The various models generally fall into two categories: those that start with change in the individual and then builds up to the community and those that start with the larger community and works down to the individual. Moving in both directions is possible and the categorization in this review does not imply only one direction but the one commonly identified in the literature or mentioned by users that responded via email. The presence or absence of a local church will influence the type of facilitation required in order to guide and integrate the values and faith of the holistic model into the community discussions and decision-making process.

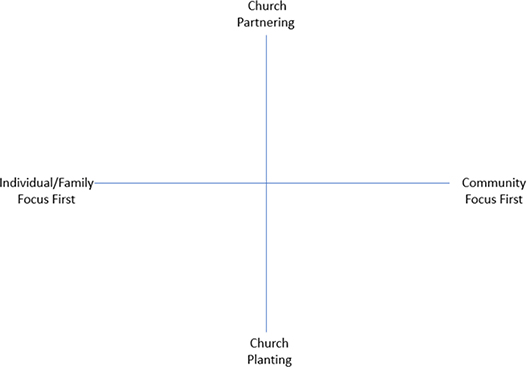

Figure 4 shows how these two themes create four quadrants where models can be placed based on their characteristics found in the literature. These themes can be seen within a few of the larger holistic models like CHE, CCM-Umoja, and the Wholistic Worldview Analysis. As an organization approaches a community project, it can place itself on this matrix based on whether or not they will be primarily engaging a community that has a church in place (partnering with the church) or if there is no existing church and the organization will be taking on more of a church planting role. Also, depending on the situation, they can consider focusing on implementing individual change first and then spreading to the community or starting at the community level and working down to individual impact. This focus on either individual or community can be seen in several prominent public health theories. For example, the Health Belief Model, Diffusion of Innovation, and Trans-theoretical Model place emphasis on individual beliefs. The Theory of Planned Behavior, Social Cognitive Theory, and Social Norms Theory seem to place an emphasis on the environment and community influences.30 Each direction of focus uses different tactics and approaches in interventions depending on the site and situation where one direction may be more appropriate to start with than the other.

Figure 4. Map of holistic health models based on the level of initiation and the presence of a local church.

While reviewing the current literature, two dominant trends appear about who the initial focus of change is. The first is the individual as the focus of change and the second is the community as the initial focus of change. Models that follow the individual first approach focus on developing the individual’s skills, opportunities, and environment as well as their faith. As the individual grows, they then reach out to others in the community and share what they have learned, hopefully serving as an example that motivates others in the community to change as well. The second trend works the other way. Change starts on a larger scale initiating community-level development projects through social consensus such as a well health education campaign or a school-based nutrition program, and then using facilitators to follow-up with families on an individual level. Although most of the frameworks tended to fall into one or the other category, a few moved back and forth between the two depending on the context. An example of this would be World Vision.28 Known for their child sponsorships, they manage to help improve an individual’s life in many ways and, through them, the life of their family and then, ultimately, the community. They also work the opposite way, starting at the communal level with health care, access to churches, and schooling, which in turn touches the individual. Both approaches can be effective depending on the community context, available resources, and the community’s readiness to change.

Another theme identified during the review of the literature is the use of existing churches or community spiritual leaders in the development process. Spirituality and worldview play a large part in how people behave and why they do what they do. Understanding this motivation is important in implementing change, therefore identifying current beliefs is essential. Utilizing existing churches or leaders can be beneficial because they already have a relationship with the people and have their trust. Church buildings and resources can also be used for house training sessions or informational meetings while creating a natural environment to discuss issues related to faith, worldview, and God. The church is often seen as a source of help and this belief can be utilized and reinforced during the transformational development process.31 True holistic development integrates the beliefs of the churches with the change and is not merely faith-placed as many secular multidimensional health models.

There may not always be an existing church in the community, and it is within these environments that many holistic health models work to plant churches. One of the benefits of this, especially for those that move from an individual to community focus, is that the community’s faith can be strengthened as individuals now have a safe place to go for spiritual growth. A church can also serve as a place of education for health and skills training. Faith-based organizations use holistic health models to come alongside the community and serve as a facilitator for change. The facilitator helps to guide the community in recognizing where growth can occur through the model. The CHE model identifies members of the community as Community Health Evangelists and trains them about disease prevention and healthy living and the biblical motivation for changing behavior. This integration of the spiritual and the physical can be traced throughout the whole development process. The CHE is tasked with meeting 10–15 households within the community and sharing what they learned with their neighbors.23 By working in small groups like this, not only do the trainers develop trust but, many times, small churches grow out of this. CCM-Umoja follows a similar process, but the facilitator works with small community groups to train community members and develop a plan for change. Other models like Opportunity International’s transformational development utilize one-on-one relationships between the facilitator and the community member.25

Facilitation not only means training the community, but it also means encouraging discussion, managing conflict, and allowing community members to feel like their voices are being heard and are important. This facilitation often involves helping communities define their worldview and assess their current situation to measure change. For example, the Light Wheel tool used in CCM-Umoja or the Ten Seed Technique used by various groups help the community identify who they are and measure where they want to go based on recognition of their worldview. In order to reach the community on certain issues, worldviews may need to be reframed, reprioritized, or reformed. The 3R model explains what this may look like as beliefs can be reframed to provide alternatives without negating the belief, reprioritized to introduce a new belief that corresponds with the behavior wanted, or reformed (directly confronting a belief about its flaws).12 This revision of world view is also seen in the Truth Centered Transformation model.24 Beliefs like “we were born poor, we will always be poor” and other fatalistic views are addressed head on and communities are presented with God’s vision of the community and the value that God places on people.

Although there is much value from the existing literature, some limitations must be acknowledged. Attempts were made to gather as many resources as possible from non-Christian faith-based organizations as possible; however, there is still significantly less non-Christian representation among the articles reviewed. Future consideration could be given to how non-Christian models differ in scope and practice. Multiple databases were used for this review, and some models may have been misinterpreted, missed, or reported in languages other than English, which were not included in the search.

There was also a lack of interviews with multiple key leadership within the faith-based organizations regarding the use of the models. This seems to be the case with much of the existing literature as well. Although informal discussions were conducted with a couple of leaders, future research may benefit from in-depth discussion with developers of holistic health models. Providing research support to faith-based organizations using these models will increase the available evidence of holistic health models and allow for a more accurate and thorough review of the models.

In reviewing the literature, it was also noticed that not much was written about advocacy or policy in holistic development. More emphasis was placed on personal relationships and work among the community than on taking on larger changes at a local or national level. This gap presents an opportunity for future developers and researchers to evaluate how faith-based organizations can act as advocates for the population that they serve and encourage participation from the community to fight for change.

This review identified and gathered many of the models that exist into a concise compilation, which can be found in the annotated bibliography available upon request. The annotated bibliography also contains information about networks and resources available to faith-based organizations.

Within the scope of holistic community health and development, many models exist. By reviewing and discussing the similarities, differences, and important themes among them, a model map was created, pointing to several important decision points in selecting a model or components that would best fit the community. Several of the larger models were identified and examples given. The goal of creating communities that know who they are (and whose they are), where they are going, and their purpose, is essential to the success of holistic community development.