Figure 1. Interview findings of denominational leaders’ awareness and understanding of F1000D

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Ruth Edith Lundiea, Deborah Merle Hancoxb

a Sikunye programme manager, Common Good, Cape Town, South Africa

b PhD Candidate and Research Associate, Department of Practical Theology and Missiology, Faculty of Theology, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa

Background: Whilst there is a growing body of research indicating the life-long significance of the first thousand days (F1000D) in a person’s life, there is currently limited research regarding the church’s understanding and support of this critical period for human health and wellbeing. Exploratory research was therefore conducted by a Cape Town faith-based organization seeking preliminary answers to the question: What is the specific contribution a local church can make in support of the first thousand days (conception to 2 years) of a child’s life in Cape Town, South Africa?

Methods: A mixed-method study was conducted with 194 respondents, seeking to understand knowledge and attitudes of church leaders towards F1000D, current church responses, existing F1000D models and approaches that may be suited to the church, the role that respondents see for the church in F1000D, and barriers to mothers accessing F1000D services.

Results: The research showed that although there is limited knowledge and engagement with F1000D by church leaders, there is broad consensus that the church does have a significant role to play in this life stage. The church has many assets that can be mobilised in support of F1000D and doing so will also serve the church’s missional purpose.

Discussion: Key recommendations include the following: F1000D should be included and normalised across all church activities; programmatic responses to F1000D that use the assets of a local church should be developed; the collective voice of the church for advocacy for F1000D support and services within society should be harnessed.

Key words: First thousand days, early childhood development, nurturing care, church, missional, social development

A growing body of evidence supports the thinking that one of the most effective ways to assist human flourishing is to ensure “a good start in life” through the provision of the basic building blocks of love, nutrition, stimulation, health, and safety to children during their first thousand days (F1000D) from conception to two years. Whilst the importance of the F1000D of life is broadly accepted by government, civil society organisations, and academia, the understanding and contribution of the local church to this important life stage is not well understood or researched. Hence, a Cape Town based non-profit organisation, Common Good, conducted exploratory research to understand the specific contribution a local church can make in support of the F1000D of a child’s life.1

The F1000D offers a “unique and invaluable window of opportunity to secure the optimal development of the child, and by extension, the positive developmental trajectory of a country”.2 Central to the importance of F1000D is the rapid development of the brain which grows up to 80% of its adult size during this period.3–6 This “once in a lifetime” opportunity of optimal brain development is dependent on the availability of supportive and nurturing environments that have a lifelong impact on the infant’s future physical, mental, and emotional health.2,3,7 The Lancet Early Childhood Development (ECD) series and subsequent nurturing care framework emphasise that all children need and have the right to receive the essential factors of nurturing care, defined as “a stable environment that is sensitive to children’s health and nutritional needs, with protection from threats, opportunities for early learning, and interactions that are responsive, emotionally supportive, and developmentally stimulating.”8,9

Around the world, an estimated 250 million children younger than 5 years in low-income and middle-income countries are born into environments that place them at risk of not reaching their developmental potential.10,11 Research has identified multiple risk factors predictive of poor early childhood development including, poverty, poor nutrition, infectious diseases, environmental toxins (especially drugs and alcohol), stress (toxic stress), exposure to violence, psychosocial risk (mental health), disrupted caregiving, and disabilities.2,11 Poverty has been shown to be a crucial risk factor which increases the likelihood of exposure to multiple adversities, including undermining the capacity of families to provide their children with the required nurturing care.7,11,12

There is an urgent call for all relevant stakeholders to prioritize and invest early in interventions aimed at reducing the risks and adversities confronting children to ensure their optimal development.3 This investment, which can yield positive lifetime developmental returns for the child, is a key lever to improving the socio-economic development of a country, benefiting the whole of society.13,14

Two factors motivate for seeking the involvement of the local church in F1000D. Firstly, the church is an important social actor in social development.15 Ter Haar and Ellis state, regarding the development sector, that “one of the greatest surprises in recent decades has been the resilience of religion”.16 Religion, they maintain, provides a powerful motivation for how many people choose to act; therefore, the worldviews of the people that social development seeks to benefit ought to be engaged. Using Korten’s typography of four social development generations gives a framework for understanding the types of social development activities in which churches engage.17 Churches are better suited to relief and charity activities (type 1) and to discipling and developing their own congregants who then go on to be change agents (type 2). The church may also serve as an activist organisation and leader in social movements for wide-scale change (type 4). In seeking the church’s engagement in social development, a religious health assets approach may be adopted, using the assets normally found within a church community.18,19

Secondly, speaking to the theological motivation for the church’s involvement, F1000D may be positioned within a framework of the mission of God — the missio Dei — and the consequent mission of the church — the missio ecclesiae. Christian mission is God's mission in which the church participates and “to participate in mission is to participate in the movement of God’s love toward people, since God is a fountain of sending love” (see John 3:16).20 God's mission is one of holistic (both spiritual and material) liberation and restoration as he seeks to bring about his kingdom, his reign, for the whole world. Churches are to “renounce an introverted concern for their own life, and recognize that they exist for the sake of those who are not members, as sign, instrument, and foretaste of God's redeeming grace for the whole life of society.”20 It is worth noting there is currently very little literature that considers the intersection of F1000D and mission. In addition, churches often struggle to implement and sustain social development programmes.21 Other barriers to the church playing a more active role in F1000D include theological frameworks that mitigate against the church’s role as a social actor,22 inadequate theological conceptualisation about F1000D, and poor engagement with issues of power and gender within the church.

The research sought to answer the question: “What is the specific contribution a local church can make in support of the first thousand days (conception to 2 years) of a child’s life in Cape Town, South Africa?”1 In answering this question, three of the areas probed were:

The research was exploratory and mixed methods including a survey, one-on-one interviews and workshops. Key informants in the research were church leaders, laity, denominational leaders, practitioners, and experts in the field of F1000D. All informants were based in Cape Town except for denominational leaders positioned nationally within South Africa. Informants were drawn from across the socio-economic spectrum of the city, but with a greater emphasis on those working in high-risk areas. Informants were purposively sampled, guided by the knowledge and connections of the research team, and was, therefore, non-probability sampling (meaning that not everyone within the research profile had an equal chance of being selected for the survey). Thematic analysis was used when analysing data. Initial coding was open, but a standard list of codes was later compiled according to emerging themes and F1000D literature, and as far as possible, this was used to classify the empirical research findings.

From a list of 150 church leader, 71 church leaders completed the survey of which 53 (75%) were male and 18 were female. Forty-five of the respondents (63%) were between the age of 41-60 years; 13 church leaders were over 60 years; 13 were under 40 years.

Semi-structured one-on-one interviews were used to collect in-depth qualitative data. Interviews were conducted with 12 denominational leaders, 11 experts in F1000D, 8 pastors, and 4 practitioners.

To gain insights from mothers and primary carers of young children, two workshops were held in high-risk areas of Cape Town (Khayelitsha and Vrygrond). The majority of attendees (70% +) were unemployed which reflects the high unemployment rates in these areas; the majority receive a South African government support grant.

The researchers sought to gain insights from church laity who were either vocationally or voluntarily engaged with children and their parents/carers in their F1000D. Participants were asked about the current and potential role of the local church to promote the wellbeing of children in F1000D. There were 40 workshop attendees from 26 different churches. Only 3 participants were men.

The research team were either employed part-time or contracted by the organisation conducting the research. All were regular and involved members at churches in Cape Town that may be described as “evangelical/charismatic.” The research team had one man (who helped with computerising the online survey) whilst the rest were women, the majority of whom are themselves mothers.

The research was carried out in line with standards for ethical research. The researchers set up their own methods for ensuring factors, such as informant anonymity, voluntary participation, non-payment of informants, the right of informants to withdraw at any time, and a complaints and ethics oversight mechanism. The Board of the non-profit organisation conducting the research agreed to act as an appeal board in case of any complaints or issues related to the research. During the research, no ethical issues arose.

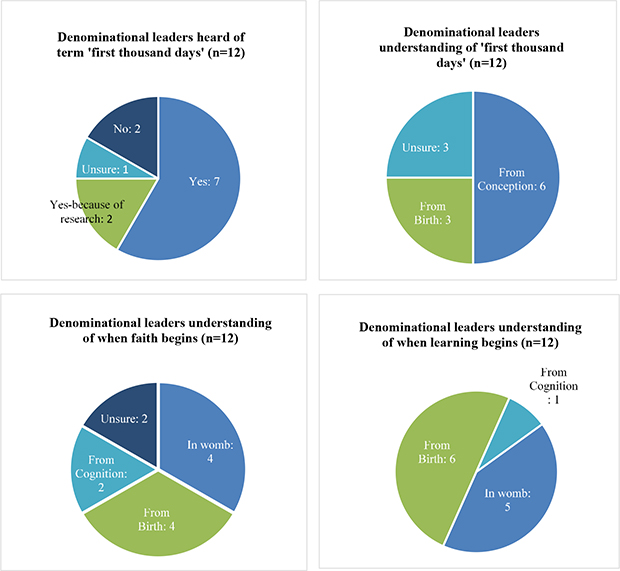

The interviews with denominational leaders explored their comprehension around the subject of F1000D. The data below in Figure 1 indicates the answers given:

Figure 1. Interview findings of denominational leaders’ awareness and understanding of F1000D

The findings indicated almost 42% of the denominational leaders had not heard of F1000D before the interview and about half recognised F1000D as starting in the womb, while more than half were not aware of the critical development that happens in the womb.

Similarly, the findings from the survey of church leaders indicated a lack of awareness about F1000D among church leaders. The survey also explored attitudes around pregnancy, showing that church leaders recognised the prevalence of stigma, judgement, and lack of community support for teenage pregnancy and pregnancy outside of marriage. Positively, the importance of fathers’ involvement in F1000D caregiving, both towards the child and mother, was recognised.

Multiple sources of empirical data were used to investigate “what are the barriers to mothers and other carers providing what is needed and accessing services during F1000D?” The interviews with experts, pastors, and practitioners were analysed thematically and responses coded. The table below shows the results using a heat map format. In the heat map, the darkest colour is used to indicate the barrier most mentioned, and the lightest colour indicates the barrier least mentioned for each group of respondents. The table itself is sorted to show the barriers most frequently mentioned across all respondent groups at the top of the table.

The qualitative data indicates four key barriers to mothers/carers accessing services and support within F1000D.

Firstly, poverty presents multiple barriers including, among other things, a lack of safe transport to service facilities, food insecurity, unemployment, or return to work shortly after birth. Secondly, a paucity of knowledge and access to information also pose barriers. These include knowledge on F1000D, available services, optimal parenting skills, and nurturing care. Thirdly, inadequate services and poor quality of accessible services, especially within the health sector, present as barriers, with mothers reportedly experiencing unfriendly and judgemental service delivery from healthcare and social-welfare professionals. Fourthly, maternal mental health, especially depression, is a critical barrier to mothers providing the nurturing care required in F1000D. This is in line with literature that shows that maternal mental health has an impact on mothers’ ability to access service and results in the “lower uptake of available services.”23

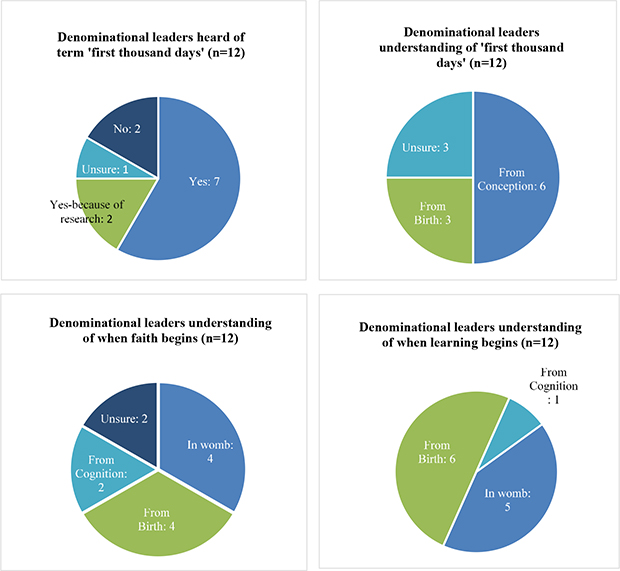

Interviews with denominational leaders asked if their denomination offered services or programmes in F1000D. Analyses of their responses were grouped across 5 target audiences and classified as either no services, congregation-based services, or a more widely targeted programme.

Figure 2. Denominations (n=12) offering F1000D services. Length of bar indicates the number of leaders who indicated their denomination does or does not conduct services or programmes for the target group

The formal programmes of denominations are generally specialised and professionally run by organisations (such as diaconic services) that play a statutory role in child protection services, as well as early childhood development centres for children 3-6 years. In a few of the denominations, these are large organisations or non-profit organisations that have been in existence for a long time and are not necessarily directly working into F1000D or with a local congregation. None of the denominations mentioned a formal programme for expectant fathers.

The survey of church pastors asked questions to explore the level of engagement with the topic of F1000D and services offered by these churches. As most participants did not provide answers to these open-ended questions, it is reasonable to conclude their church does not provide any services to pregnant mothers, expectant fathers, parents or caregivers, and babies (0-2years).

Over half of the surveyed participants indicated they had services for children (3-6years). Similarly, the interviews with pastors found that churches are more actively and intentionally involved with children aged 3 - 6 years, with this engagement predominately anchored in Sunday school programs. Additionally, expectant fathers and fathers of little children were found to be under-served within local churches. The services most offered to pregnant mothers and expectant fathers are of a supportive nature, with some offering capacity development workshops and training. Respondents also mentioned general congregational support.

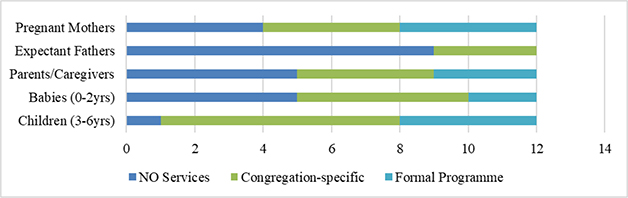

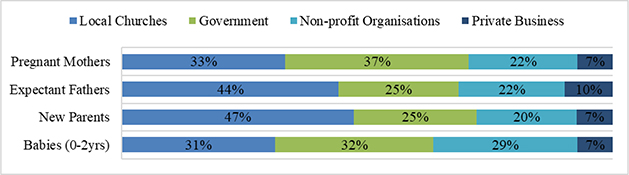

Survey respondents were asked who they thought should be providing services to these target groups — they could indicate any one or all of the following as service providers. The results to this question are depicted in the chart below.

Figure 3. Survey finding for who should be providing services in F1000D

These findings indicate that survey participants believe that churches are a major role-player in the provision of services, particularly to parents/caregivers within F1000D.

Firstly, the pastors surveyed were asked, in an open-ended question, to describe the role in F1000D of a well-resourced church and a church in a vulnerable area. The responses were analysed thematically, and the results are depicted using a “heat map” format.

The role of providing support, especially as it pertains to providing a “safe space” in the community for mothers and children (in both a physical and emotional sense) is seen as important for all churches, as well as capacity building and providing material resources. Within vulnerable areas, the church is seen to have an added role in providing educational services for children.

In the interviews, experts, denominational leaders, pastors, and practitioners were asked to give their opinions on the role of the church in F1000D. They were specifically asked to differentiate between the role of a church in a high-risk area and a church in low risk area; the two heat maps below show the analysis of these responses.

Across all interviewee groups there was consensus that the most important role of the church in a vulnerable area is to provide support to parents. These churches are also seen to have a role in building the capacity of parents, especially around parenting skills, providing resources to vulnerable families, providing educational/stimulation services for children, and then effecting changes within the church, especially around delivering factual information to overcome misconceptions or lack of knowledge.

According to those interviewed, churches in low risk areas also have a key role in providing support to parents. However, there is a definite expectation from both those interviewed and surveyed that churches in low risk areas need to be connecting and partnering with churches in vulnerable areas in ways that are more intentional and relational, as opposed to merely passing on material resources. Church in low risk areas can also play a role in financially supporting non-profit organisations (including faith-based organisations) working with families in F1000D in vulnerable areas.

This research sought to explore “the specific contribution a local church can make in support of the first thousand days (conception to 2 years) of a child’s life in Cape Town.” All the results point to consensus amongst clergy, laity, experts, and practitioners that the church does have a specific and influential role to play in supporting F1000D. At the same time though for the church to contribute effectively, the one key finding points to low awareness and knowledge within church leadership around F1000D issues and the importance of the church’s involvement. This finding is supported by a report delineating the gap between what experts know about early childhood development from science and what public understanding is.3 This is a key barrier for church involvement and would need to be addressed.

There are multiple levels of engagement for churches, dependent on the context, assets, and strengths of the local church. A model for church and F1000D is to integrate the finding with two existing models, namely church strengths, drawn from the religious health assets literature and the Social Ecological Model (SEM).18,24 When examining the many roles that the church can play in support of F1000D, and looking at the various risk factors and protective factors as well as the barriers to accessing services for carers in F1000D, the researchers identified that the SEM gives a helpful framework to bring all of these parts together. The SEM is “a theory-based framework for understanding the multifaceted and interactive effects of personal and environmental factors that determine behaviours and for identifying behavioural and organizational leverage points and intermediaries for health promotion within organizations”.24

The church is well positioned within the SEM to play an influential role into all five hierarchical levels of the SEM, namely, individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and policy/enabling environment.24 The Christian faith is present across all levels of the SEM through individual Christians seeking to live out their faith at these various levels. The opportunity exists, therefore, for the organised church, through its members and its individual and collective organisational forms, to support F1000D. In South Africa, the church is still one of the most trusted institutions that convenes a substantial proportion of the population on a regular basis.25 Therefore, the church has leverage in all of the areas within the SEM.

Gary Gunderson proposes eight inherent strengths of local churches which can, should, and do shape communities. These include strengths to accompany, convene, connect, tell stories, give sanctuary, bless, pray, and endure.18

The following discussion presents some preliminary ideas of how the church can interact with F1000D based on the findings in this research and bringing the strengths of the church and all the levels of the SEM together:

To interpret the multiple levels of engagement for the church in F1000D, three approaches are recommended linked to Korten’s generations of social development.17

In this approach, Korten’s first generation (Type 1),17 ways would be sought to encourage and assist a local church (and wider church bodies, such as denominational structures, ministers’ fraternals, and training institutions) to grow in their knowledge and awareness of F1000D issues and the support of F1000D activities within the local church. This would involve moving F1000D people (infants, parents, etc.) and topics (conception, pregnancy, fatherhood, etc.) from the periphery of church activity into the mainstream activities of a church. It could also include some relief activity in the wider community but would be predominantly focused on the well-being of F1000D people within their own church community. Church based responses should also include the everyday activities of church members, like visiting people in their homes. Churches should start by developing interventions that assist their own members in F1000D and then move outwards into the community. Churches should seek “church-suited” existing initiatives and look at their current responses and see if they can be more coordinated, strategic, and informed by science to make an even bigger impact. As discussed in the Lancet ECD series, emphasis should be placed on interventions that enable caregivers to provide “nurturing care” hence enabling young children to achieve their developmental potential.8

In this approach, Korten’s second generation (Type 2),17churches can run F1000D programmes in their church and surrounding (or other) communities. These could be, for example, home visiting programmes, parental training and support programmes, clinic support programmes, fatherhood programmes — to name but a few. Such programmes would be best run in partnership with specialist NGOs, faith-based or secular, and wherever possible in conjunction with other churches in their area. Some level of integration between the science of F1000D and the beliefs and practices of the church could be obtained through collaborative approaches. Churches need to adjust their programmatic approaches based on their context and resources and consider the respective roles of churches in low and high-risk areas.

Given the scope of the church in South Africa, a third suggested approach is for the church (locally and collectively) to be one of the institutions mobilising society (including its own members) to address the failure of political, societal, and cultural systems beyond its own community in support of F1000D. This advocacy and influence approach reflect Korten’s third and fourth generations of social development.17 This could in time lead to the church contributing to a national movement of people who live in an active awareness of this critical phase of life.

Whatever approach is adopted, churches need to be helped to provide non-judgemental, inclusive parental support to all whilst continuing to hold to what it believes to be God’s best design for family. This is premised on God’s redemptive and restoring grace for those in difficult and different life circumstances — both individually and as societies.

This exploratory research has highlighted three topics that require further research and investigation regarding strengthening the church’s response to F1000D. Firstly, there is a requirement for deeper theological reflection on F1000D. Whilst there is quite extensive theological engagement with childhood and youth, there is very limited engagement specifically with F1000D. It is under-represented across the theological disciplines, both in South Africa and globally. Early childhood has received attention in discussions on doctrinal issues such as sin and baptism, but the importance of this age group to the wellbeing of people, the church, and society more generally has not received adequate attention. This probably accounts for its limited and sporadic attention in the local church. Secondly, further research is required into fatherhood and initiatives effective in engaging men and fathers to promote their active, positive involvement in F1000D. There is a noticeable gap in programmes and interventions that specifically target men, both within society and churches. Thirdly, there is scope for further academic research into the various topics addressed within this exploratory research, specifically around the barriers that prevent access to F1000D services and providing the necessary nurturing care within a South African context. The limitations and possible barriers to church’s involvement also need to be investigated further with regards to financial implications and testing workable models.

The research, undertaken in Cape Town, South Africa, shows that the church has a significant role to play in supporting F1000D. Given the extent of the church in South Africa, the potential for the individual and societal impact of a F1000D enabled and active church is significant. However, it also shows that effective engagement with F1000D is a gap within the church. Given the unique life-long impact this phase has on the quality of life, it is an area about which no church or Christian should be ignorant or avoidant. Hence, there is a need for interventions to increase the awareness, knowledge, and skills in churches around F1000D and to equip churches to use their unique assets and strengths in this area. The findings of this research have wider application than Cape Town, South Africa. Given the international call to invest early11 and the critical nature of F1000D, there is relevance for the church globally to contribute as discussed above and support F1000D. Jesus Christ, the head of the church, desires that all people should live life to the full (John 10:10). The church is well placed to make a significant contribution to this life by engaging more fully with people in their F1000D and equipping and supporting parents and communities to provide children with the responsive, nurturing care they require for optimal development.