Figure 1

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Gretchen Slovera, Kelsie Martinezb, and Kathrin Barnesc

a MS, Psy.D., LMFT, MALaw, Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist

b MA, Doctoral student, pre-dissertation, Alliant International University, San Diego, CA;. Pre-Doctoral Internship completed with Veteran’s Administration Pacific Islands; Post-Doctoral Internship pending with San Diego Veteran’s Administration, San Diego, California.

c BA Psychology; San Diego Christian College. Currently employed as a director of client relations.

Background: This research was birthed in 2017 during a trip to Lusaka, Zambia, with the purpose of offering fourth-year, medical students attending the University of Zambia, School of Medicine, lectures on psychology topics as part of their clinical studies. Students were also offered brief therapy sessions where they could process thoughts and feelings causing them internal struggles. The subject of offering counseling on a regular basis was randomly discussed with the students. From these discussions the need for this research became evident, with the intent of becoming the launching pad to brainstorm the most effective ways of developing a plan to offer counseling services for all medical students attending the University of Zambia School of Medicine.

Methods: An-experimental research design, consisting of completion of a 12-item questionnaire administered by paper and pen. The inclusion criteria were the fourth year, medical students attending the University of Zambia, School of Medicine.

Results: The student responses revealed that most of them had little to no experience with counseling services, but a strong desire for them.

Discussion: The goal of this study was to simply establish a need for an on-campus counseling service, the need of which has been established by the very students who would benefit. With the acceptance of this need, the future plan is to explore the different ways in which this need can be fulfilled with minimal costs to the Medical School Program.

Conclusion: This study is the first step towards identifying the needs of the medical students and sets the ground-work for further research into the specific areas of need and mental health challenges. More specificity in the area of demographics of students will produce a more comprehensive picture of the areas of concentration for the therapists offering services.

Key words: campus counseling, counseling, medical students, the University of Zambia School of Medicine, mental health, stress, therapy

The University of Zambia School of Medicine located in Lusaka, Zambia, is an institution that offers education to those seeking a doctoral medical degree. The institutional mission statement is “to provide quality education in health sciences producing competent graduates who value lifelong learning and are well prepared to undertake specialist training programs and able to provide patient care and leadership in medical research that addresses the priority needs of Zambia.”1

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of The University of Zambia, School of Medicine and San Diego Christian College, located in Santee, California. The aim of this research was to identify if the medical students at the University of Zambia School of Medicine, believed they would benefit from an offering of on-campus counseling services if made available to them on a regular basis. Fourth year medical students were chosen to participate due to the academic demands placed on them at this stage of their studies.

According to a study by Mwanza, Cooper, et al. (2010), “to a large extent in Zambia, people who are mentally ill are stigmatized, feared, scorned at, humiliated and condemned the mental health services situation in Zambia could be described as critical, requiring urgent action.”2 The University of Zambia falls into this category of needing urgent support, as counseling services are not readily and consistently available to students on campus. There is no research on the current topic of suicide amongst medical students in Zambia.

The School of Medicine was chosen after interacting with fourth year medical students during their clinical studies in May 2017. A team of medical doctors, mental health professionals and students, headed by Dr. Cheryl Snyder (deceased) organized the clinical studies, which included a component of mental health curriculum. These conversations revealed that many students lack the resources to freely speak with a therapist about concerns from past experiences and present struggles. The challenges of a medical student are many as they struggle to learn the material, balance relationships and respond to cultural obligations and expectations.

The specific objectives are to assess the needs of fourth year medical students as they are facing a turning point in their studies and are challenged to complete clinical testing in order to proceed to their fifth year of studies. It is hoped that if the need is identified, a creative method of delivering services can be developed for the students. The ultimate goal would then be to produce graduates of the doctorate program who have addressed their own personal challenges and acquired valuable coping skills. When encountering patients who would unknowingly trigger a disturbing response, the treating physician will not be distracted. Instead, they will have the ability to deliver their services in a more competent and concise manner. The medical program’s reputation for producing competent, caring physicians will be enhanced, which, in turn, could result in an increase in program enrollment and produce a positive financial impact.

Some research has been conducted, which has explored the mental health issues that challenge medical students. Suicidal ideation has been the focus, and some have concluded that a medical school student is not likely to seek assistance for a variety of reasons.3 There has been little research on suicide rates in Zambia. A 2004 study tracked documented suicide rates in Zambia from 1967–1971 and found the following rates (per 100,000 of the population per annum): 6·9 for all African residents, 11·2 for African males, 2·2 for African females and 12·8 for all Africans above the age of 14 years.4

This study is meant to focus on one particular location, in order to first establish a need and then to implement a program using already established resources.

The University of Zambia School of Medicine has been training those in the medical field for over fifty years. Throughout their medical school training, medical students often experience stressors rooted in academia, as well as residual and present life experiences. It is known that unresolved life issues tend to fester and grow into problems that manifest in all areas. Medical school is a challenge in itself. When a student does not have the resources available to address inner conflicts and struggles, the outcome can affect both their ability to retain information, treat their patients and maintain their own physical and emotional health. In 2013, Feeney, Jordan and McCarron5 set out to eliminate the stigma that mental health issues could not be overcome. They implemented a recovery model to be used while teaching medical students about mental illness.5 Research conducted before the study showed the common belief that individuals struggling with certain types of mental illness were “as unaccepting as lay people” and these beliefs showed an overall lack of empathy towards the patients.5 The negative connotation often associated with mental illness can lead medical students to overlook and discount the impact that mental illness can have on patient symptoms and recovery. In another study conducted by Francesca Vescovelli and colleagues, the increase in mental conditions such as anxiety, depression and stress seen in college students was the subject of research.6 These authors acknowledged that there should be measures taken for “the importance of devoting a special clinical attention to college students who attend medical courses.”

Mental health illness is a broad topic of special interest that often generates negative attitudes towards people who experience such problems. Negative attitudes are not solely owned by the lay public but often extend into the academic programs that produce future medical providers, in particular, medical doctors.5 The stigma of mental illness extends into the medical school curriculum due to the lack of teaching about mental illness. “It has been argued that through such teaching, students can gain a depth of understanding of psychological distress not accessible through traditional clinical placements.”5 Feeney et al. concluded that when medical students are taught “recovery principles” for mental health issues, the services they offer have better outcomes. It also helps to broaden their narrow mindset about mental illness.5

It has been stated and known that medical students have a higher risk of experiencing “depression, suicidal ideation and burnout;” however, it was also found that the nature of the medical schooling system or university in which the student attends, is one of the biggest contributors to a student exhibiting these symptoms.3 It is then crucial that the educational board deems their students’ mental health as a priority and implement preventative and reactive treatment for their students. This can be done through the implementation of “university counseling centers, community providers, and university psychiatry faculty who may be called on to consult in urgent cases.”3 Through this implementation at various universities in the United States, it was shown to help students who not only felt better supported, but displayed increased accuracy and performance as well.3

There have been studies to show that due to increased stress caused by various factors, medical students experience higher occurrences of physical ailments, which could, in turn, lead to what is known as a burnout.7 The study defined burnout as, “a three-dimensional syndrome that includes emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment.”7 Each one of these issues exhibited in the registrar, or medical student, identified an increased inability to care for their patients or themselves to the best of their ability.7

In 2002, Tyssen, and Vaglum reviewed and expanded upon the impact of patient care. Studies showed that a medical student or physician who had untreated personal issues were more likely to wrongly diagnose and treat their patients.8 This would not only negatively impact the patient, along with potentially diminish their health even further, but would also be a financial loss for the hospital when needing to provide two treatments due to the fact that the first treatment was not effective due to doctor’s error. Because of these risks, it is crucial that medical students and physicians be given adequate treatment along with monitored and healthy work environments.8

The cultural and societal shifts that emphasize wellness must be considered in any counseling service offered in an academic setting.9 There are standards and guidelines that recognize best practices for these services. They have been produced by the International Association of Counseling Services (IACAS) and the Council for the Advancement of Standards (CAS).9

In a study of the differences between suicidal behaviors in Austrian and Turkish medical students, it was found that cultural factors play a role in the differences in behaviors and attitudes towards suicide and reactions to suicidality.10 In certain professions, suicide has become a significant health problem. Doctors succumb to suicide more often than other professions, and medical students are also at great risk for suicide. Often, the precursor to suicide is depression and medical students often experience depressive symptoms as a result of the performance pressures of academia. Add personal relationship challenges and the result is a lethal cocktail that can be diluted with proper resources.10

The knowledge of the increased risk factors for physicians committing suicide has been linked back to 1958 in England.11 The research found that “Most strikingly, suicide is a disproportionately high cause of mortality in physicians, with all published studies indicating a particularly high suicide rate in female physicians.”11 The consensus went on to state how not only identifying this epidemic, but, implementing easily obtainable treatment for risk factors such as depression, substance abuse, and anxiety, would “have a multiplier effect for medical students, residents, and patients.”11

In 2005, Dahlin, Joneborg and Runeson delved into the outlook medical students held on the impact their environment and stressors had on their studies. It was concluded that as each year of schooling went by, the students experienced an increase in stress and toxicity levels “Year 6, both the latter factors were rated highly, but Year 6 students also gave higher ratings than the 2 other groups to non-supportive climate.”.12 This outlook implies that it may have been beneficial to implement assistance as early as year one for the medical students to adjust their viewpoint.

Through the growing awareness of the need for mental health assessments, the stigma against mental health treatment is believed to decrease. Cristina Vladu and her colleagues believed that through implementing mental health training for medical students, physicians and all medical staff to both undergo and perform, there will be a greater understanding of the benefits these treatments have on patients as a whole. They determined that, “A new approach to medical education should include early exposure of medical students and other trainees to behavioral sciences and to the development of interpersonal skills and team building approach to enhance the cultural competence of the health care workers.”13 Increased awareness and training, in turn, allows the opportunity for change and understanding among the medical students and those under their care.

As students experience psychological distress, their personal and academic development and accomplishments are negatively affected. The current study to determine the need for a counseling program for medical students attending the University of Zambia, School of Medicine, can effectively add to the literature of cross-cultural mental health needs and differences as there is scant literature which explores the attitudes and efficacy in this area of study. It has been established that medical students experience stressors that are unique to their academic program. This, along with the residual, unresolved mental health stressors from family/relationships, creates the perfect storm. It is projected that addressing a need for counseling assistance as a precursor for developing the resource will not only enhance the lives of medical students and patients they treat, but will also identify the University of Zambia, School of Medicine as leaders in their care of students.

This is a non-experimental research design, consisting of the completion of a 12-item questionnaire administered on paper. The inclusion criteria were the fourth-year medical students attending the University of Zambia, School of Medicine. This choice was influenced by the critical level of their studies in the fourth year. A need for offering a structured course of therapeutic counseling services to fourth year students was identified through providing brief counseling services on a modified schedule over twenty days in May 2017 during student participation in their clinical studies program.

For the purposes of this study, all other students outside the fourth year were excluded. The study site is the University of Zambia, School of Medicine, located in Lusaka, Zambia. The size of the sample was determined at the time of administration of the questionnaire, based upon the number of fourth year medical students enrolled in the University of Zambia, School of Medicine, as well as the number of students who voluntarily participated.

One hundred fifty two (152) fourth year medical students attending the University of Zambia, School of Medicine were on the official census. Out of 152 students, there were 109 students who participated by completing the questionnaire, 4 students declined to complete the questionnaire, 4 students completed the questionnaire without signing the consent form and 35 students were absent the day the survey was administered. The charts below represent the responses to the questionnaires completed by students who also signed the consent form (n-109). Each question required a Likert scale response of Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral/Not Applicable, Agree, and Strongly Agree to each question.

Demographic questions were purposefully not included in the questionnaire due to the fact that the focus was exploratory in nature and did not require such information. The focus group solely consisted of fourth year medical students.

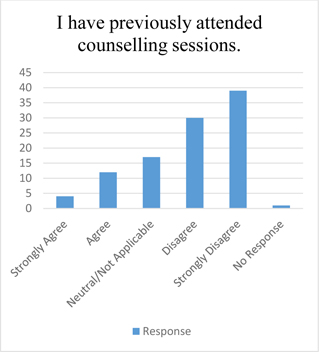

Figure 1 reflects that many of the students had not participated in counseling themselves as a resource to discuss problems and concerns. Eighty-one percent of students responded with Disagree or Strongly Disagree. Those students who responded Neutral/Not Applicable and No Response did not respond with a yes or no and, therefore, were not included in calculating the response percentage.

Figure 2 signifies that question 2 cannot be accurately interpreted as 16 students reported attending previous counseling in Question 1 but more than 16 students responded in agreement or disagreement regarding the benefit of their counseling experience in Question 2.

As Figure 3 illustrates, the students establish that their studies are a source of depression when they feel pressured. Eighty-eight percent of students responded with Strongly Agree, Agree, or Neutral/Not Applicable.

Figure 4 indicates that eighty-nine percent of students responded with Strongly Agree, Agree, or Neutral/Not Applicable.

Figure 5 displays that ninety four percent of students responded with Strongly Agree, Agree or Neutral/Not Applicable. Students’ answers to 4 and 5 establish that their studies can be a source of anxiety and stress.

Figure 6 displays that in answer to question 6, the students demonstrate their resilience, in that they find they can function adequately in their off campus lives in spite of the pressures of their academic lives. Thirty-nine percent of students responded with Strongly Agree or Agree. Sixty-one percent of students responded with Disagree or Strongly Disagree. Those students who responded Neutral/Not Applicable and No Response did not respond with a Yes or No and, therefore, were not included in calculating the response percentage.

In Figure 7, it can be seen that the majority of the students agreed that they are challenged by time management concerns. Ninety percent of students responded with Strongly Agree, Agree or Neutral/Not Applicable.

Figure 8 reflects that a large number of the students did not find their family problems to interfere with their studies. Forty-five percent of students responded with Strongly Agree or Agree. Fifty-five percent of students responded with Disagree or Strongly Disagree. Those students who responded Neutral/Not Applicable did not respond with a Yes or No and, therefore, were not included in calculating the response percentage.

Figure 9 signifies that the majority of students surveyed indicated they agree that counseling services are needed. Ninety-eight percent of students responded with Strongly Agree, Agree or Neutral/Not Applicable.

Figure 10 reflects that the majority of students surveyed indicated they would make use of a counseling service on campus. Ninety-two percent of students responded with Strongly Agree, Agree or Neutral/Not Applicable.

Figure 11 reflects that over half of the students surveyed can identify a peer who could benefit from on campus counseling. Eighty-eight percent of students responded with Strongly Agree, Agree or Neutral/Not Applicable.

Figure 12 reveals that students overwhelmingly expressed their belief that the addition of a counselling service on campus will have a positive impact on students as they achieve the milestones of their academic careers. Ninety-six percent responded with Strongly Agree, Agree or Neutral/Not Applicable.

Four (4) students answered the questionnaire, but they did not sign the consent form. Their responses were not included in the result tabulations. However, it is worth noting that their responses were consistent with the responses of the general population and regarding the establishment of counseling service on campus for the benefit of all students while they are working their way through medical school.

The student responses revealed that most of them had little to no experience with counseling services. The majority of them experience anxiety, depression and stress due to their studies. They do not have enough time in the day to complete what is expected of them. Despite these struggles, they appear to have the resiliency to function off campus and nearly half of them report that family situations do not interfere with their studies. The greater majority of the students do, however, believe that counseling services are needed on the University of Zambia, School of Medicine campus and that they would make use of these services if they were available. The majority of students also stated that they know of a fellow student who would benefit from these services and that they believe the counseling services on campus would produce positive results for students as they progress through academic life. It would be a disservice to ignore the needs and desires of these students who are dedicating lives, time and energy to a lifetime of serving others.

There is no doubt that medical school creates a unique struggle for those who are called to serve their fellow man through medicine. Motivations differ as everyone has their own reasons for pursuing a career that can either help people prolong life as well as come to terms with the end of life. The fourth year medical students attending the University of Zambia, School of Medicine are no different in what they experience during their season in academia than other medical students, as they all have to absorb the knowledge and prove their mastery of the application in order to progress. In some ways, it may be more difficult for the Zambian to achieve their goals due to cultural roadblocks, financial stressors and lack of appropriate support systems.

The goal of this study was to simply establish a need for an on-campus counseling service, the need of which has been established by the very students who would benefit from it. With the acceptance of this need, the future plan is to explore the different ways in which this need can be fulfilled with minimal costs to the Medical School Program. The benefits of establishing a counseling program on campus has the potential to produce medical doctors who have addressed their own stressors, worries and fears. As they are exposed to patients from all walks of life, they will also have the ability to recognize those stressors, worries and fears in the patients they treat, which will, in turn, assist them in all areas of treatment. A physician who has worked through and processed events in their lives which were stress provoking will have a better outcome with patients who may otherwise trigger past memories upon contact. A mentally healthy physician will have developed the coping skills to move into their practice without the added struggle of masking their own past mental pain.

This study is the first step towards identifying the needs of the medical students and sets the ground-work for further research into the specific areas of need and mental health challenges. More research in this student demography will produce a more comprehensive picture of the areas of concentration for the therapists offering services.

The University of Zambia, School of Medicine will be known as innovators in the care of their medical students, producing physicians who are not only academically competent but mentally strong as well. The implementation of a counseling program for the students could also have a positive financial impact on school enrollment. Academic excellence will include development of the whole person as a representation of school success.