Figure 1. Self-reported perceived health status at the individual, family, and community levels (n = 96)

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Claudia Balea

a BA, School of World Studies Department, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA

Objective: The aim of this mixed-methods study is to capture and understand impoverished Guatemalan community members’ perspectives of their own health needs on a community level in order to guide Hope of Life (HOL) Non-Profit organization’s health promotion interventions in the villages they serve.

Methods: This exploratory research deployed a modified health needs assessment survey with 96 participants from four impoverished villages in the department of Zacapa, Guatemala. Survey responses were analyzed for significant differences in 4-item individual, family, and community health scores across demographic variables and significant correlations with reported personal health conditions and children’s health conditions. Five semi-structured interviews were also conducted with community leaders from three of the villages surveyed. Interviews were audio recorded and responses were transcribed verbatim and translated from Spanish to English. Thematic analysis using HyperRESEARCH qualitative analysis software version 4.5.0. was conducted to identify major themes.

Results: The mean age of the 96 participants surveyed was 40.4 years and the majority were women, married or in consensual union, and have children. Women reported a significantly lower individual and family health score than men. The most rural village included in the study had significantly lower family health scores than the three sub-urban villages in the study. Among the personal health problems reported by participants, alcohol consumption, dental problems, and malnutrition were significant predictors of lower individual health scores. Themes that emerged from the interview analysis included the greatest community health needs, perceived negative community health behaviors, barriers to health care access, HOL’s impact, and suggestions for community health promotion.

Conclusion: The results of this study reveal many unmet health needs and barriers to healthcare that Guatemalan village communities face. Community-based participatory research using a mixed approach voices communities’ perspective on their perceived needs and is an important tool to guide non-profit aid and intervention serving impoverished communities.

Key words: global health, Guatemala, community health, health needs, FBOs, health promotion

The population of Guatemala is close to 16.3 million with nearly two thirds of the population living on less than US$ 2 per day.1 Poor, rural, and indigenous populations suffer some of the worst health outcomes in the country.2 Despite progress in the past decade in improving population health among the most vulnerable groups, health disparities, and inequality in health outcomes and access to medical care remain an ongoing challenge.3,4

Faith based organizations (FBOs) and other non-government organizations (NGOs) have been playing an increasing role in health promotion in Guatemalan communities for decades, but remain under researched and are often underrepresented in conversations surrounding international community development and health promotion.5 Hope of Life International Organization (HOL) is one such faith-based, non-profit organization based out of Río Hondo, Zacapa, Guatemala, working to provide humanitarian aid to communities in Eastern Guatemala.6

Through HOL directly or World Help Organization serving as a liaison, churches, businesses, and schools in the United States can take part in the Village of Transformation project (VTP), which funds long-term, mission projects in one village community per funding US organization.7,8 The VTP includes a variety of community projects determined by established community needs and can include clean water wells, family homes, schools, church buildings, and sponsorship program establishment.7,8 The sponsorship program is continuously funded by US organizations to cover educational, nutritional, and medical expenses of children in these communities.7,8 No public health data has been collected to date concerning the rural and suburban villages in the department of Zacapa, Guatemala impacted by HOL involvement.

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is an approach to incorporate the voices of underserved groups into the research process to increase health equity and better development of health promotion interventions.9 This study incorporates a mixed-methods approach informed by CBPR to collect the perspectives of community members in four Guatemalan villages impacted by the VTP. Engaging community members and leaders allowed more culturally-centered approaches and valued community members as equal contributors to the health inequity solutions that non-profit organizations set out to solve.10,11

The aim of this study is to capture and understand impoverished Guatemalan community members’ perspectives of their own health needs on a community level in order to guide HOL health promotion interventions beyond the current community projects in the villages they serve. Community members’ perspectives and evaluation can be used to inform and guide decisions made by HOL in order to best address the health needs of these communities, empower individuals in these communities, and improve their quality of life. Appropriate targeting of HOL health promotion efforts according to community needs can serve to improve health outcomes of the villages in the study and other villages impacted by HOL programs and inform other NGOs working in Guatemala.

This study applied a mixed methods approach using both quantitative and qualitative methods including a survey questionnaire with community members and semi-structured interviews with identified community leaders. Quantitative data reported by community members was further supplemented by qualitative interview responses from community leaders. This approach allowed for a broader understanding of perceived socioeconomic needs and health needs significantly affecting community members at individual and community levels. Research materials were influenced by the 2018 John Hopkins Community Health Needs Assessment and created to account for time constraints on data collection and cultural factors of the communities.12 This exploratory research project was conducted with university institutional review board approval (Institutional Review Board of Virginia Commonwealth University: Protocol number HM20015622).

The sample consisted of participants that were residents of the community for over three years and at least 18 years of age. Survey participants were conveniently sampled, and those who were identified to meet the study criteria were asked to participate and the purpose of the study was explained. If they agreed, they offered verbal consent prior to survey administration. Surveys were anonymous, and no identifiers were recorded. Each participant self-administered the survey and completed it on paper, which was later transferred to an Excel spreadsheet and the paper copy destroyed. Survey questionnaires were written in Spanish and read aloud in Spanish as needed.

Survey questions were analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) performed with the goal of identifying some number of independent variables (predictors) that have a linear relationship with the dependent variable. Data fields in the survey measures included personal, family, and community health status score rated on a 4-item scale: excellent, good, normal, poor, not sure. These scores reflected subjective perception of participants’ own health status, their overall immediate family’s health status, and their overall community’s health status. Results were converted to a numerical score 1–4, with 1 corresponding to poor and 4 corresponding to an excellent health score. A response of “not sure” was scored as a 2, effectively combining them with “normal” results. In many of the questions, these scores were treated as the dependent variable in a linear model with remaining survey demographic information treated as independent variables. If a predictor was identified as statistically significant by the ANCOVA, a two-sample T-test or a Tukey’s honestly significant difference test was performed (Tukey Test). A two-sample t-test was almost exclusively used when health scores were significantly different by gender. The Tukey test was used to identify which villages had the greatest difference in health score and if any villages had a significantly lower score than all other villages.

The sample for the personal interviews consisted of community leaders of their respective villages, who had been residents of that community for over three years and were at least 18 years of age. Potential participants identified as community leaders by community members were asked to participate and the purpose of the study explained. If they agreed, verbal consent was obtained, and interviews were conducted in Spanish by the researcher and a preapproved HOL Guatemalan staff member. Interviews were recorded and quickly transcribed and translated verbatim; audio files were kept confidential until deleted. The original methodological design called for eight interviews to be collected, two from each village surveyed, but due to time constraints and access to the villages, only five were collected, none from Village A and only one from Village C.

The five participants interviewed included: a pastor and a village leader, who serves as a liaison between her village and HOL, were interviewed from village B; the President of the School Board, who also serves as a community advocate, was interviewed from Village C; and a school principal and pastor were interviewed from Village D. Interview responses were transcribed and translated to English. Themes from the interview responses were coded by the author using HyperRESEARCH qualitative analysis software version 4.5.0.

A total of 96 participants completed the questionnaire from the four different villages classified as nonagricultural or agricultural and semi-urban or rural (Table 1).

The average age of survey participants is 40.4 years and most participants are female, married or in a consensual union, and have children or grandchildren. (Table 2)

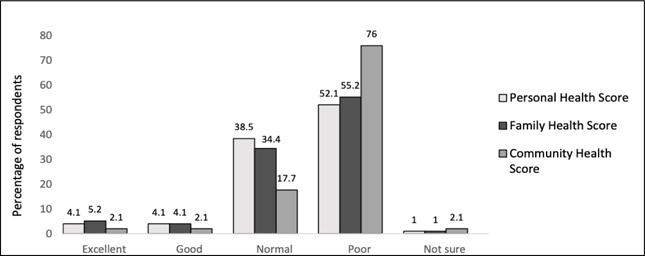

Figure 1. Self-reported perceived health status at the individual, family, and community levels (n = 96)

A majority of participants reported poor personal, family, and community health scores (Figure 1). Results indicated that men reported a significantly higher individual health score than women with a p-value of 0.039. None of the other variables—village of residence, age, marital status, or whether or not the individual had children—tested as significant.

The results indicated that men also reported a significantly higher family health score than women with a p-value of 0.025. Whether a village was classified as rural (Village C) or not (Villages A, B, and D) was also found to be a predictor of reported family health score. The resulting t-test showed that Villages A, B, and D combined had a significantly higher family health score than Village C; the p-value for the test was 0.001. No other variables tested significant.

Results indicated that Village D was the only village to show a significantly higher community health score compared with Village C, the most rural village with a p-value of 0.014. Village D had a higher community health score than Village B, but not significantly higher with a p-value of 0.08.

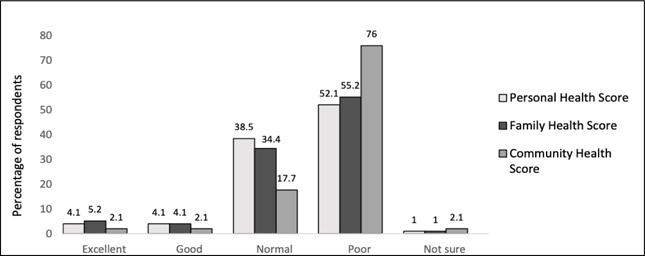

Figure 2. Self-reported personal health problems experienced in the last three years

Among the most common health problems experienced by participants in the past three years, 49/96 participants reported dental problems, 35/96 reported malnutrition, 34/96 reported asthma or trouble breathing, and 24/96 reported mental health concerns (Figure 2). Demographic variables were controlled for in order to identify if any health concerns correlated with a lower health status score. The results indicated that alcohol consumption with a p-value of 0.003, dental problems with a p-value of 0.009, and malnutrition with a p-value of 0.03 were significant predictors for a lower individual health status score.

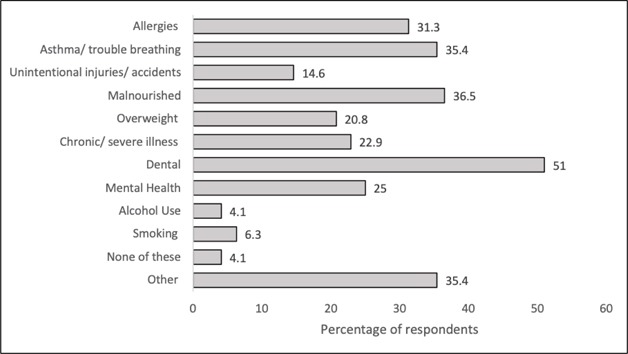

Figure 3. Self-reported health problems children or grandchildren experienced in the last three years

Eighty-seven of ninety-six (87/96) participants with children reported the health conditions experienced by their children or grandchildren under the age of 18 in the last three years (Figure 3). Among the most common health conditions of participants’ children or grandchildren under the age of 18 experienced in the last three years included 40/87 reporting malnutrition, while 23/87 reported children being overweight. 36/87 participants also cited birth-related problems and 28/87 cited dental problems among children. Demographic variables were controlled for in order to identify if any health concerns reported for participants’ children or grandchildren related to lower family health status score. No child health conditions tested as significant predictors of family healthcare status at the alpha 0.05 level.

The top themes focused on the greatest community health needs, perceived poor community health behaviors, barriers to healthcare access, Hope of Life’s impact, and suggestions for community health promotion. All quotations were translated from Spanish to English.

All respondents mentioned malnutrition as being one of the most severe health needs for their respective villages. Unclean environments and infectious diseases were also cited by three respondents from Villages B and D. Chronic conditions were also mentioned by Respondent 5 from Village D.

Many people don’t have sewage systems, their drainage is out in the open. So, when they do their laundry and everything, the chemicals from the soap they used go to the soil. It turns into mud and where we get mosquitoes and insects from (Respondent 1).

They don’t have the economic resources when they contract dengue fever. There’s a public hospital, but it doesn’t have the means to treat this disease, and some kids have died. They brought down three children with dengue fever from the villages. They got bloated stomachs, bleeding from the nose or even from their ears, and a low platelet count. The disease can be deadly if there are not means to treat the children (Respondent 4).

. . . There’s much fever. It comes with vomiting, diarrhea, malnutrition, which has become an issue because there are no means to nourish these children. All these diseases stem from malnutrition. The children lack medicine, they lack vitamins. Mothers don’t take enough vitamins during pregnancy, so many children with incapacities are being born (Respondent 5).

Community leaders mentioned specific health behaviors they perceived as having a negative impact on their community’s health. Respondents from Villages B and D cited poor hygiene practices, such as poor hand washing habits, bathing practices, and consuming unclean drinking water. The respondent from Village C reported lack of family planning despite available resources due to widely held attitudes of machismo or a strong sense of masculine pride among husbands and male partners. This respondent reported this attitude leads male partners to associate pride with a large family size despite insufficient resources. Women who would like to receive birth control or family planning counselling are often not supported by their male partners or accompanied to the health center, located over an hour away from their community. A respondent from Village D noted poor nutritional decision-making such as choosing food with low nutritional value over healthier alternatives.

Because sometimes kids get sick with parasites, and it’s because of that, lack of hygiene. If they taught them about hygiene, perhaps the children and even the adults would not fall sick (Respondent 1).

Parents could put in place healthier habits when they cook, pay more attention on good nutrition for the children instead of buying them sweets (Respondent 4).

A while ago, when we didn’t have... the drugs we have now, people had a lot of children, and they didn’t have birth control. Now it’s only because the men don’t want to — like I said, there is sexism, and they don’t try even though the woman wants to. That’s how things have always been. If you’ve visited the families, you can see a lot of them are big (Respondent 3).

The most common barrier to health mentioned by all respondents was difficulty in accessing health center services and medicines. All the respondents reported from 30 minutes to over two hours’ travel time to the nearest health centers from their communities. They noted that many of the pharmacies and health centers were not sufficiently stocked with needed medications. They reported that community members often do not seek out healthcare treatment or medicines due to the lack of financial resources. Respondent 3 from Village C also reported safety as a concern especially in regard to transportation to receive healthcare services. Respondent 3 notes that sexual assault and rape is a recurrent problem for women traveling to the health center over an hour away from their village community.

For here, the greatest benefit would be a health center where we could have better medical attention, better drugs, a better health system, where a patient can go and tell the doctors their ailments. Perhaps that way they can get better faster. Because sometimes, due to the long distance from town, when a patient gets there, the drugs are out of stock and they have to buy them. And sometimes you can’t afford them (Respondent 3).

But there’s people who don’t have any money and they can’t get treatment. They die because they don’t have money (Respondent 4).

Sometimes [my wife] will say, “I want to go to the health center in Peña Blanca. It’s an hour’s walk away.” So, I make the trip with her. But other people don’t. They let the women go alone. And the thing is there have been rapes along the way. That’s a recurring issue we have. I think a closer health center would be beneficial and would be essential to help us solve a problem we’ve always had (Respondent 3).

But [a health clinic] needs to be organized and well-run. Because there’s been aid brought to some other places, but those things get sold. And the people are left without resources, or medicine, or whatever. So, it needs to be run by good-hearted people, people who are willing to help, not make profit off of it. That’s not been possible because sadly, there hasn’t been an institution willing to do it (Respondent 5).

Three respondents cited the benefit of the Hope of Life sponsorship program and other community projects as part of the Village of Transformation project in providing access to immediate or emergency healthcare for sick children. All respondents reported that HOL had made an overall positive contribution to meeting health needs in their community. Some respondents still feel that there is room to improve health outcomes in their community with HOL support.

Hope of Life is in charge of the medical and nutrition aspects. For example, if a kid is sick, he comes to me and I call [Hope of Life] to see if there’s a chance for a medical appointment. If they approve, they have to go there (Respondent 2).

Some kids are sponsored, and for their medical appointments, I call the person in charge and she lets me bring one or two kids for treatment. But they have to be sponsored. The kids who aren’t sponsored are taken to the hospital, or given traditional remedies, because there’s no money for medical expenses (Respondent 5).

The most important thing [Hope of Life] has promised us is that if someone has a fall, breaks an arm or other bruises, we communicate that to them and they send us medicines and assistance to treat them. That’s the benefit we get from them (Respondent 3).

[The health needs of this community] have not been established yet. . . I haven’t seen much aid coming through. Some specific needs, for [Hope of Life] gives them access to what they need. Like I said, they’ve received that from [Hope of Life], but not from other institutions (Respondent 1).

Three respondents from Villages B, C, and D showed an interest in mobilizing the community and working with institutions such as Hope of Life to make improvements in preventative measures in health, uplifting well-being, and spirituality, as well as addressing existing needs. Respondent 1 from Village A noted a project committee to address community needs and another institution to provide public health education would be beneficial to improving health outcomes. Respondent 3 from Village C specifically cited the need for housing projects and educational scholarships. Respondent 5 from Village D suggested establishing a spiritual program to improve the well-being of community members.

First of all, create a committee, and then have that committee establish the projects to carry out. Like I said, with the church, we start by bringing a pound of rice, a pound of . . . basic grains. So, if people could bring one pound of each thing to help them (Respondent 1).

So, there should be some institution that comes and says, “Look, we’re going to talk about health. This is what you need to do and this is how you do it.” . . . If they taught them about hygiene, perhaps the children and even the adults would not fall sick (Respondent 1).

There are about 20, 25 homes that could be improved, perhaps one or two a year. There’ve been people who’ve told me, “Why don’t we make a request to get at least some tin sheets?” Because there are houses that don’t even have roofs (Respondent 3).

I think the people from Hope of Life can help us with scholarships for [the children here] to have a better education and have a better life than we’ve had (Respondent 3).

Another thing [to make the village healthier] would be a spiritual program. . . [to] promote that we are safe with God. It’s the only way to — God is our doctor, He is our advocate, He is our provider, He is everything (Respondent 5).

In order to guide future non-profit intervention, the effect of a wide range of communicable and noncommunicable diseases on individual health and communities’ health was examined. Findings showed that women have poorer self-rated health than men. It has been shown that poor Guatemalan women experience less access to education and health services and face discriminatory attitudes, including a culture of machismo among other patterns of exclusion.13,14 The rural village had lower individual health scores than the sub-urban villages included in the study. These findings are consistent with a World Bank report citing that more isolated communities with limited access to road networks have less access to health services, other institutions, and economic opportunities.13

Malnutrition was significantly correlated with lower self-rated health scores for adults, while 20 and 21 participants reported obesity and chronic illness as personal health problems, respectively. Asthma and allergies were also the third and fourth most commonly reported personal health problems. Community leaders cited poor health habits coupled with malnutrition and infectious disease as a challenge for their resource-limited communities. These finding are consistent with the growing trends in developing countries where increasing rates of non-communicable diseases such as obesity and chronic respiratory disease are coupled with existing burdens of malnutrition and infectious disease in resource poor areas.14 In addition to malnutrition, dental problems and alcohol use also significantly predicted lower individual health scores for participants and should be considered by HOL and non-profit programs as areas to target program efforts.

Nearly half of the participants with children or grandchildren under 18 reported that malnutrition affected their children or grandchildren, while over a quarter of participants reported that their children or grandchildren were overweight. Similar to participants’ personal health problems reported, allergies and asthma were the 3rd and 4th most common children’s health problems reported, respectively. The second most common reported health problem for children was problems at birth, including low birth weight, premature birth, or complications with delivery. The HOL sponsorship program provides nutritional support to children and families in their program in order to address malnutrition, but pre-natal care, health education, and medical intervention may be future areas of intervention to consider.

Community leaders cited economic and institutional barriers in accessing healthcare and the ability to overcome health issues. All community leaders were in consensus that healthcare services and medication are often inaccessible. All community leaders responded that there were no health centers located near their communities, and travelling to the closest health center was difficult for most community members. Participant 3, from the most rural village, specifically cited long transportation times that were very dangerous for women traveling to the nearest health center. The difficulty in accessing health services is consistent with survey data from the Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Vida (ENCOVI 2014) that poorer Guatemalans are more likely to not have access to health facilities and even when they do have access, these health centers are often understaffed and lack medication.15

Community leaders reported that non-profit programs and aid from HOL have been positive overall, but there is room for more projects, improvement in health education, and higher education opportunities. Community leaders were eager to start health promotion and education initiatives. HOL can capitalize on this enthusiasm of community leaders through fostering a collaborative, long-term relationship to guide health promotion and intervention design and implementation. This engagement can play an important role in including and empowering community members in improving health outcomes.

The health needs identified here can serve as a baseline for further investigation into the health needs of impoverished Eastern Guatemalan villages served by HOL and non-profit organizations to inform health promotion programs. Future surveys and interviews can continue to conduct health needs assessments in these areas, getting further feedback from communities on how to properly address health concerns and design health promotion strategies engaging village communities.

This study faced several limitations, including a potential for response bias and limited generalizability. Implicit bias due to the researcher being from a different culture as well as language and cultural barriers could all serve as further limitations to accurately collecting and analyzing the data in this study. The overall sample consisted mostly of women, and the survey sample size was small, specifically in Village A. The interview sample size was small and lacked greater representation of all the community leaders in each village. This study served to identify perceived health problems and barriers in these communities and to get a glimpse of possible solutions specific to each villages’ needs. This study also does not assess the impact of specific programs HOL already has in place.

The results of this study identify the many unmet health needs, numerous socioeconomic barriers to accessing health services, and environmental factors impacting health that Guatemalan village communities face. Communities’ perspectives on their perceived health needs are an important tool to guide and educate HOL and other non-profit programs to best meet the health needs of the various village communities served through maximizing the impact of non-profit interventions and aid.