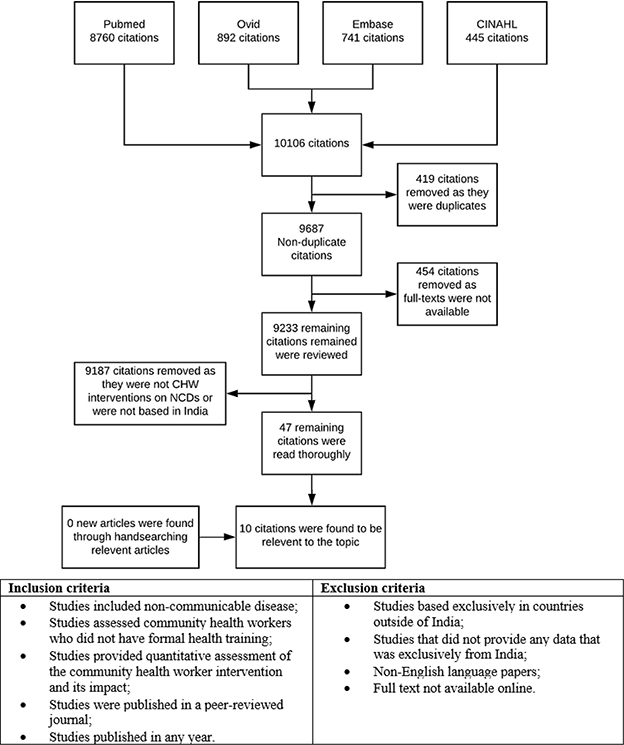

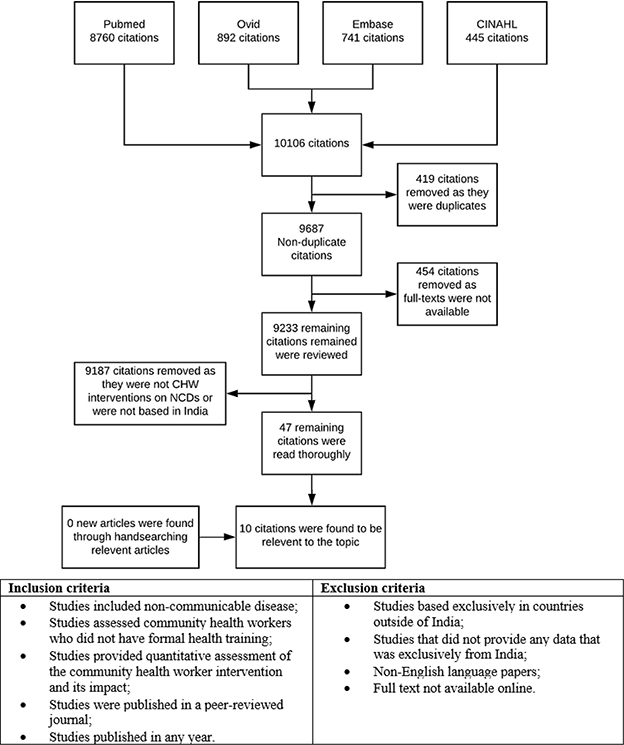

Figure 1. Selection criteria for articles

REVIEW ARTICLE

Alexander Milesa, Matthew J Reeveb, Nathan J Grillsc

a BBiomed, MD, The Nossal Institute of Global Health, University of Melbourne, Australia.

b MBBS, MPH, Senior Technical Officer, The Nossal Institute of Global Health, University of Melbourne, Australia.

c DPHIL, DPH, MBBS, MPH, Professor, The Nossal Institute of Global Health and the Australia India Institute, University of Melbourne, Australia.

Background and Aims: Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) account for 61% of deaths in India. This review focuses on Community Health Workers’ (CHW) effectiveness in preventing and managing NCDs in India which could help direct future research and government policy.

Methods: A search of PubMed, Ovid, Embase, and CINAHL using terms related to “community health workers” and “India” was used to find articles that quantitatively measured the effect of CHW-delivered interventions on NCD risk and health outcomes.

Results: CHW interventions are associated with improved health outcomes, metabolic parameters, and lifestyle risk factors in diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and oral cancer. Current literature on CHW interventions for NCDs in India is limited in the number of studies and the scope of NCDs covered.

Conclusion: There is weak to moderate evidence that CHWs can improve NCD health outcomes in India.

Keywords: Public Health, Systematic Review, Non-Communicable Disease, Community Health Workers, India

More than three-quarters of deaths attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and most are preventable.1 Economic development and social changes in LMICs have resulted in dietary changes, reduced physical activity, and better access to healthcare to treat infectious diseases. These changes have contributed to NCDs overtaking infectious diseases as the primary burden of disease in LMICs including India.2-4 In India, cardiovascular disease now accounts for over 25% of deaths,5 and diabetes cases in India are expected to reach 79 million by 2030.6

India has an extreme shortage and maldistribution of healthcare workers. The density of doctors per capita in India is one-quarter of World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendations, and while 74% of India’s 1.25 billion people live in rural areas, most doctors work in cities.7

To overcome healthcare shortages, task-shifting can be employed wherein tasks are delegated to less specialised health workers. For example, a community health worker (CHW) may fill roles previously done by a nurse. CHWs are health workers who receive limited training to deliver healthcare but have no formal qualifications directly related to healthcare.8

Systematic reviews of CHW interventions in the USA and in LMICs other than India show that compared with standard care, CHWs can improve health outcomes for breast cancer, hypertension, and diabetes, and improve medication adherence and cardiovascular disease risk factors.8-10

China was the first country to implement a large-scale CHW program during the 1920s.11

Illiterate farmers were trained to become barefoot doctors who recorded births and deaths, administered first aid, vaccinated children, and gave community health education talks.11

By the 1970s, it is estimated that there were over one million barefoot doctors in China.12 The First Global Health Conference in Ata, in what is now Kazakhstan, increased interest in community health worker programs with an aim to deliver “Health for All.”12 However, a global recession in the 1980s led to many of these initiatives dissolving, without the necessary funding and resources.13 There were successful CHW programs in LMICs during the 1980s in Brazil, Nepal, and Bangladesh. These countries all achieved improvements in child mortality throughout the 1990s.14 Other countries to invest in CHWs since 1990 include Uganda, Ethiopia, Pakistan, and India.12

Government-funded health programs led by CHWs started in India in the 1970s.15 These CHWs, called anganwadi workers, administer basic health care to young children and mothers including nutrition education, growth monitoring, and referral to appropriate services.16 In 2005, the Indian Government launched a new CHW program called the National Rural Health Mission, where over 700,000 Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) were recruited to work in their own communities.4 Their roles include maternal counselling, encouraging births in hospitals, newborn nutrition education, infection prevention, and referral to appropriate services.4 Non-government organisations also run community health projects and employ CHWs independently.17

Launched in 2010, the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Stroke (NPCDCS) aimed to use government-employed CHWs to also target NCDs in India.18

Despite the widespread adoption of CHWs in healthcare delivery, there is a paucity of data on the effect of CHW interventions on NCDs in India. This is significant because India has over one-sixth of the world’s population and over 2.3 million CHWs, or 40% of the world’s total.19,20 Current literature on CHWs has not specifically focused on India but has focused on infectious disease prevention and maternal and child health (MCH). This review examines the effectiveness of CHWs in the prevention and management of NCDs in India to help guide future research and policy.

On 16th June 2020, four online databases were searched (PubMed, Ovid, CINAHL, and Embase) from inception date using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 1. This strategy was derived from search strategies of previous systematic reviews on CHWs’ effectiveness.10,21

Search terms focused on CHWs and India (Appendix 1 - Search Strategy). NCDs represent numerous medical conditions and no specific NCD search terms were used to prevent the unintentional omission of articles. Instead, irrelevant results were manually excluded during the screening process.

For this review, WHO’s definition of NCDs was used, which outlines NCDs as chronic diseases resulting from a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental, and behavioural factors.22 Mental health conditions were excluded to limit the review to chronic physical conditions. Diseases and deaths caused by trauma, home and work accidents, natural disasters, human environmental hazards, pregnancy, and disability were excluded because they did not meet the criteria for NCDs in this review.

The definition for CHWs was “any health worker whose work pertains to healthcare delivery, who is given training in the context of the intervention and who has not received a healthcare degree.” This definition was based on a Cochrane review of CHWs.8

The effectiveness of CHWs was defined as their ability to improve participant health outcomes or to improve disease risk factors as measured by a statistically significant change when compared to standard care.

Article titles and their abstracts were initially screened by two researchers (AM and MR) based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were only included if they focussed on NCDs, used CHWs as a direct intervention, and quantified the CHW intervention effect compared with either baseline or standard care. Only primary articles published in peer-reviewed journals were included. Studies were excluded if they were based outside India, not published in the English language, or the full text was unavailable. Articles were not excluded based on the year of publication.

Full texts were evaluated using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria by the same researchers. References of chosen articles were screened to identify further studies. A third researcher (NG), an expert on public health in India, was consulted in cases where inclusion or exclusion was disputed.

Down and Black’s checklist23 was used to analyse each study’s design quality (Appendix 3). For randomised control trials (RCTs), reporting quality was analysed with the Consort checklist.24 (Appendix 4) For non-NCTs, the TREND25 statement checklist was used (Appendix 5). The quality assessment was not designed to exclude any articles. Grey literature was not searched to give the review reasonable quality.

Figure 1. Selection criteria for articles

| Author | Year | Study type | Sample size | Location | Type of CHW | NCD | Target Group | Intervention | Comparison | Duration | |

| Risk | U/R* | ||||||||||

| Tian et al.26 | 2015 | RCT | 1050 | Haryana (and Tibet) | Volunteer community members | Cardio-vascular | High | Rural | Lifestyle modification, medication prescription, and adherence | Standard cardiovascular management program | 12 months |

| Xavier et al.27 | 2016 | RCT | 805 | India-wide | Not specified | Cardio-vascular | High | - | Medication adherence program | No intervention | 12 months |

| Sharma et al.28 | 2016 | RCT | 100 | - | Trained non-physician health worker | Cardio-vascular | High | - | Assessment of cardiovascular disease risk factors and drug adherence | Standard care group | 24 months |

| Kar et al.29 | 2008 | RCT | 400 | Haryana and Chandigarh Union Territory | Not specified | Cardio-vascular | Low | Mixed | Cardiovascular risk screen with referral to doctor for treatment | No intervention | 5 months |

| Kar et al.29 | 2008 | Cohort study | 1010 | Haryana and Chandigarh Union Territory | Not specified | Cardio-vascular | Low | Mixed | Cardiovascular risk screen with referral to doctor for treatment | Baseline | 5 months |

| Khetan et al.30 | 2019 | RCT | 1242 | West Bengal | Community Health Worker | Cardio-vascular | Low | Rural | Health and lifestyle education. | Standard Care | 2 years |

| Balagopal et al.31 | 2008 | Cohort study | 703 | Tamil Nadu | Trained science graduates without health degree | Diabetes | Low | Rural | Health and lifestyle education | Baseline | 6 months |

| Balagopal et al.32 | 2012 | Cohort study | 1638 | Gujarat | Not specified | Diabetes | Low | Rural | Health and lifestyle education | Baseline | 6 months |

| Jain et al33 | 2018 | RCT | 322 | Maharashtra | Community Health Worker | Diabetes | Low | Rural | CHW health checks, telephone contact, and medication adherence checks | Standard Care | 6 months |

| Sankaranarayanan et al.34 | 2005 | RCT | 167741 | Kerala | Non-physician health worker | Cancer | Low | Mixed | Screening program for oral cancer | Standard Care | 9 years |

| Shet et al.35 | 2017 | RCT | 1144 | Karnataka | Lay Health Worker | Anaemia | Low | Rural | Health and lifestyle education | Standard Care | 6 months |

Note. * Urban/Rural

| Author | NCD | Duration | Key Findings | p-value |

| Tian et al.26 | Cardiovascular | 12 months | Medication adherence higher (46.7% vs. 17.9%) | p=0.002 |

| Xavier et al.27 | Cardiovascular | 12 months | Medication adherence higher (OR 2.69) | 95% CI 1.36–5.34 |

| Systolic blood pressure in Intervention Group vs. Standard Care (124.4 vs. 128.0 mmHg) | p=0.002 | |||

| Increased smoking cessation (85% vs. 52%, OR 5.46) | p<0.001 | |||

| Increased physical exercise (89% vs. 60%, OR 5.23) | p<0.001 | |||

| Increased vegetable consumption (62% vs. 52%, OR 1.48) | p=0.04 | |||

| BMI reduction (-0.9kg/m2 vs. no change) | p<0.0001 | |||

| Sharma et al.28 | Cardiovascular | 24 months | >80% Medication adherence higher (24% vs. 8%) | p=0.003 |

| Systolic blood pressure in Intervention Group vs. Standard Care (124.9 vs. 135.4mmHg) | p<0.001 | |||

| Increased smoking cessation (80% vs. 18%) | p=0.010 | |||

| Improved BMI (24.2 vs. 26.1) | p=0.002 | |||

| Improved physical exercise at 12 months (96% vs. 50%) | p<0.001 | |||

| Improved cholesterol at 12 months (152.7 vs. 176.7 mg/dL (3.95 vs. 4.57 mmol/l)) | p=0.008 | |||

| Improved fruit and vegetable consumption (16% vs. 43.8% eating low amounts of vegetables) | P=0.003 | |||

| Kar et al.29 | Cardiovascular | 5 months | Intention to quit smoking compared with no intervention (37.2% increase vs. 2.3% increase) | p<0.05 |

| Increase in medication adherence compared with no intervention (27.9% to 58.3% vs. decrease from 43.5% to 34.8%) | p<0.05 | |||

| Decrease in systolic blood pressure in high risk individuals compared with baseline (145.6 vs. 154.4 mmHg) | p<0.001 | |||

| Khetan et al.30 | Cardiovascular/ Diabetes | 24 months | Systolic blood pressure in Intervention Group vs. Standard Care (142.8 vs. 153.2mmHg) | p=0.001 |

| FBG improvement in intervention group compared with control (-43.0mg/dL [-2.39mmol/L] vs. -16.3mg/dL [-0.91mmol/L]) | p=0.29 | |||

| Reduction in cigarettes consumed in intervention group compared with control (-3.1 vs. -3.3) | p=0.62 | |||

| Balagopal et al.31 | Diabetes | 6 months | FBG* reduction in diabetics (60.2mg/dL [3.34mmol/L]) | p=0.031 |

| FBG reduction in prediabetics (11.9mg/dL [0.66mmol/L]) | p=0.001 | |||

| FBG reduction in healthy individuals (3.2mg/dL [0.18mmol/L]) | p=0.045 | |||

| FBG reduction in prediabetic youth (18.5mg/dL [1.03mmol/L]) | p=0.014 | |||

| Balagopal et al.32 | Diabetes | 6 months | FBG reduction in diabetics (19.08mg/dL [1.06mmol/L]) | p<0.001 |

| FBG reduction in prediabetics (6.02mg/dL [0.33mmol/L]) | p<0.001 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure reduction in diabetics (6.21mmHg) | p<0.001 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure reduction in prediabetics (8.57mmHg) | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure reduction in healthy individuals (7.21mmHg) | ||||

| Increased fruit and vegetable consumption (an increase of 0.04 serves of fruit and 0.19 serves of vegetables per day) | p<0.001 | |||

| Increased physical exercise (increase from 24.4 to 38.0%) | p<0.001 | |||

| BMI reduction in diabetics (1.05%) | p<0.001 | |||

| Jain et al.33 | Diabetes | 6 months | Systolic blood pressure in intervention vs. control (126.03 vs. 128.69) | p=0.651 |

| Fasting blood sugar in intervention vs. control (148.33mg/dL [8.24mmol/L] vs. 153.40 [8.52mmol/L]) | p=0.654 | |||

| Post-prandial blood sugar in intervention vs. control (226.11mg/dL [12.56mmol/L] vs. 236.17mg/dL [13.12mmol/L]) | p=0.391 | |||

| Total cholesterol in intervention vs. control (173.11mg/dL [4.48mmol/L] vs. 169.08mg/dL[4.37mmol/L]) | p=0.67 | |||

| Sankaranarayanan et al.34 | Cancer | 9 years | Reduced mortality from oral cancer in consumers of tobacco and/or alcohol receiving screening intervention compared with standard care (mortality rate 29.9 vs. 45.4) | p=0.03 |

| Shet et al.35 | Anaemia | 6 months | Anaemia cure rate at follow-up in intervention group compared with control (55.7% vs. 41.1% – RR 1.37) | 95% CI 1.04–1.70 |

| Improvement in Hb in intervention group compared with control (1.087 vs. 0.829 – difference of 0.257 g/dL) | 95% CI 0.07–0.44 |

Note. *FBG = Fasting Blood Glucose

In total, 9,687 non-duplicate articles were found, 9,640 were not studies on CHWs or NCDs in India, or the full text was unavailable. Of the 47 remaining articles 10 remained after full text screening (Figure 1).

Seven studies were RCTs,26-28,30,33-35 two were cohort studies,31,32 and one article involved multiple studies, with components of both RCTs and cohort study design29 (Table 1).

Two studies were conducted in Haryana26,29 and one each in Tamil Nadu,31 Gujarat,32 Kerala,34, West Bengal,30 Maharashtra,33 and Karnataka.35 One study27 was based across 14 states which were not named. Another trial26 was based in both Haryana in India and Tibet in China; however, only the Indian data were analysed in this review. One article29 was based on Haryana (state) and Chandigarh, which is a union territory. Another article28 did not specify where it was based. Four studies occurred only in rural areas,26,31-33 two were in both urban and rural areas,25,30 and two did not clarify their settings27,28 (Table 1 - Study Characteristics).

Four studies used the term “community health worker.” 27,30,32,33 “Non-physician health worker (NPHW)” was used in three articles.28,29,34 “Community health volunteer,”26 “lay health worker,”35 and “trained trainer”31 appeared once each (Appendix 2 - Summary of CHW Characteristics). In this review, “community health worker" covers all terms.

In general, CHWs’ demographics were not well documented. No articles stated the CHWs’ ages. Only two articles reported CHWs’ gender, where both men and women were used.28,29 CHWs’ levels of education varied from year 1027 to tertiary education31,34 and was stated in only four articles27,31,32,34 (Appendix 2 - Summary of CHW Characteristics).

Five studies specified that non-government CHWs were recruited,26,28 and only one used the term “anganwadi workers”.35 No studies had ASHAs (Appendix 2 – Summary of CHW Characteristics).

Training duration varied from one day26 to six months.31 Three studies33,34 did not specify the training length. Only three articles26,27,30 mentioned CHWs’ payments (Appendix 2 - Summary of CHW Characteristics).

Five studies targeted cardiovascular disease.26-30 Three studies addressed diabetes,31-33 and there was one study each on oral cancer34 and anaemia35 (Table 1 - Study Characteristics).

All studies on cardiovascular disease24-30 concluded that CHW interventions were effective for cardiovascular disease management (Table 2 - Key outcomes of CHW interventions). Tian et al.26 found a CHW-led surveillance program with lifestyle modification and medication follow-up that was associated with higher medication adherence (taking medication of >25 days in the past month) in a rural cohort aged over 40 years with cardiovascular disease when compared with standard care (46.7% vs. 17.9% at twelve months, p=0.002). Xavier et al.27 compared a CHW-led medication adherence program with one providing standard care in patients admitted to hospital with acute coronary syndrome27 and reported increased medication adherence (taking >80% of prescribed medications) (97% vs. 92%, p=0.006). Sharma et al.24 also found higher adherence (taking >80% of prescribed medications) in patients with acute coronary syndrome following a CHW intervention compared with standard care (24% vs. 8%, p =0.003).24 Kar et al.29 discovered that CHWs’ cardiovascular screening and referral of high-risk individuals to a doctor was associated with increased medication adherence at five months compared with no intervention (27.9% to 58.3% in intervention vs. 43.5% to 34.8% in control, p<0.05).

Xavier et al.,27 Sharma et al.,28 and Khetan et al.30 reported lower systolic blood pressure in the intervention group compared with standard care (124.4 vs. 128.0 mmHg at 12 months, p=0.002),23 (124.9 vs. 135.4mmHg at 24 months, p<0.001),24 and (142.8 vs. 153.2mmHg at 24 months).26 Kar et al.29 also found reduced systolic blood pressure when the post-CHW intervention was compared with the individual’s baseline (145.6 vs. 154.4 mmHg at five months, p<0.001).

At twelve months, Xavier et al.27 reported improved smoking cessation (85% vs. 52%, p<0.001), increased physical exercise (89% vs. 60%, p<0.001), higher fruit and vegetable intake (62% vs. 52%, p=0.04), and BMI reduction (-0.9kg/m2 vs. no change, p<0.0001) in the intervention group. Similarly, Sharma et al.28 found improved smoking cessation (80% vs. 18% cessation rate, p=0.010) and BMI at 24 months (24.2 vs. 26.1, p=0.002) in the intervention group. Kar et al.29 also found a higher intention to quit smoking at five months (25.5% vs. 60.3%, p<0.05) compared with the baseline. In contrast, Tian et al. and Khetan et al.26,30 did not find a correlation between the intervention and smoking cessation at twelve months and 24 months, respectively.

There were three articles on diabetes.30-32 The two articles by Balagopal et al. were both cohort studies and suggested that CHW-led health education and lifestyle interventions could improve metabolic parameters compared with the baseline (Table 2 - Key outcomes of CHW interventions). At six months, in one trial,31 the intervention was associated with reduced fasting blood glucose in patients with diabetes 13.4mmol/L to 10.0mmol/L (p=0.031), in prediabetic patients 6.02mmol/L to 5.36mmol/L (p=0.001), and healthy individuals 5.24mmol/L to 5.07mmol/L (p=0.045). In youth (10–17 years old) with prediabetes, fasting blood glucose was reduced (104.5 [5.81mmol/L] to 86.0mg/dL [4.78mmol/L], p=0.014). At six months, the more recent study32 reported blood glucose reduction in patients with diabetes (165.6mg/dL [9.2mmol/L] to 151.5mg/dL [8.4mmol/L], p<0.001) and patients with prediabetes (107.7 [5.98mmol/L] to 101.9mg/dL [5.66mmol/L], p<0.001). Additionally, fruit and vegetable consumption (1.84 serves to 2.05 per day, p<0.001) and moderate–vigorous physical exercise (24.4% to 38.0%, p<0.001) increased in all groups. Jain et al..33 compared standard care with CHW visits and telephone contact over 6 months for patients attending diabetic clinics. While results tended towards improved blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, post-prandial blood sugar, and cholesterol, none were statistically significant compared with standard care.

Khetan et al..30 also looked at fasting blood glucose in their cardiovascular risk factor trial. It showed trends towards reduction in fasting blood glucose in people with diabetes receiving the intervention compared with no intervention (decrease by 43.0mg/dL [-2.39mmol/L] vs. -16.3mg/dL [-0.91mmol/L], p=0.29), but it was not statistically significant.

Sankaranarayanan et al..34 ran a CHW-led oral cancer screening intervention which showed that the intervention was associated with reduced oral cancer mortality over nine years (29.9 vs. 45.4 per 100,000, p=0.03) compared with standard care.

Shet et al..35 organised a lay-health worker intervention to reduce rates of anaemia in children with anaemia. At six months, the anaemia cure rate was higher in the intervention group as compared to control (55.7% vs. 41.1% – RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.04–1.70). There was also an improvement in average haemoglobin levels in the intervention group compared with control (1.087 vs. 0.829 – difference of 0.257 g/dL, 95% CI 0.07–0.44).

Study quality scores ranged from 1729 to 2526 out of a possible 26 relevant questions for RCTs (Appendix 3). For the two non-RCTs, the study quality scores were 1232 and 1431 out of a possible 20 relevant questions (Appendix 3). The reporting quality scores for RCTs ranged from 1833 to 2835 out of a possible 33 relevant questions (Appendix 5). The reporting quality scores for the two non-RCTs were 2632 and 3131 out of 54 relevant questions (Appendix 4). All studies except Tian et al.22 and Jain et al.34 failed to describe the CHW training and intervention adequately enough to allow for replication. Studies that rated worse in study quality, such as Kar et al.,25 Sankaranarayanan et al.,33 and Shet et al.,35 did not list potential adverse effects of CHW interventions, describe loss to follow-up characteristics, or state funding sources. Similarly, Balagopal et al.’s two non-RCTs31,32 did not list adverse effects of CHW interventions, or describe or list loss to follow-up characteristics. RCTs that scored worse in reporting quality, such as Kar et al.,29 Sankaranarayanan et al.,33 and Jain et al.,34 did not report on how participants were randomised, how reporters were blinded, and what methods of subgroup analysis were used.

This systematic review found weak to moderate evidence that CHWs in India can improve medical outcomes in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and childhood anaemia. It also found moderate evidence that they can influence risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. There is weak evidence that CHW interventions can improve the detection of oral cancer.

Systematic reviews on CHWs targeting NCDs exist8-10 and suggest that CHWs could improve health outcomes in the areas of breast cancer, hypertension, medication adherence, and diabetes. They also suggest that CHWs could lower lifestyle risk factors including weight, physical exercise, and smoking rates.

Training duration and the incentives, both monetary and non-monetary, CHWs receive affect performance.32 Studies in this review did not comment sufficiently on incentives CHWs received or the content of CHWs’ training.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first review of literature on CHWs specific to India, despite India having a significant proportion of the world’s population and CHWs.20 Additionally, this is the first review that focuses on CHWs targeting only NCDs in an LMIC.

The literature on cardiovascular disease suggests that there is moderate evidence that CHWs can improve medication adherence and reduce lifestyle risk factors.

There is also moderate evidence that CHWs can improve fasting blood glucose, blood pressure, and lifestyle risk factors in low risk individuals based on two studies by Balagopal et al.31-32 However, in another article from Jain et al.,.33 there was no statistically significant improvement in fasting blood glucose, post-prandial blood glucose, blood pressure, and triglycerides in patients with diabetes compared with standard care. The latter article attributed this to the duration of the study and small sample size. There was weak evidence for the benefit of CHW involvement in oral cancer screening programs and improving anaemia rates in children.

The improvements in NCD health outcomes seen in CHW interventions suggest that there are benefits in broadening the scope of CHWs in India to also target NCD in addition to infectious diseases and MCH.

Only Shet et al.35 used “anganwadi workers” and none used “ASHAs” in their intervention despite these government CHWs constituting the majority of CHWs in India.20,37,38 ASHAs and anganwadi workers currently work in their own communities in simple health education and providing referrals to health care services and would, therefore, be prime candidates for leading NCD interventions. Skills used by CHWs, such as child and maternal nutrition advice, are easily transferable to include simple interventions targeting diet and lifestyle. Currently, few NCD interventions utilise government CHWs because they work predominantly in MCH. ASHAs have only existed since 2005, and they work in public healthcare although India’s healthcare is highly privatised.39

Surprisingly, only eleven articles were mentioned in this review despite CHWs in India numbering 2.3 million20 and India’s high burden of NCDs.5,6 This suggests that there is a significant gap in current research on the potential CHWs may have in improving NCD health outcomes, and this warrants further research. This article supports increasing funding and resource allocation to national NCD health policies that utilise CHWs. Research could also guide new policy as NCDs become a higher proportion of India’s burden of disease. There is also the opportunity for local governments and hospitals to expand already existing CHW projects to include interventions against non-communicable diseases.

Compared with another systematic review on CHW interventions to improve NCD in other LMICs, the results from the research in India also suggests that there is weak to moderate evidence that CHW can improve NCD health outcomes.9 Compared with other LMICs, there is proportionally less research on CHWs in India given the number of CHWs in India.9

This review found that some NCDs are underrepresented in CHW interventions. These included cerebrovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, chronic kidney disease, and cancer, which are in India’s top ten causes of mortality.40 These NCDs may have the potential for CHW interventions for primary or secondary prevention.

It is difficult to generalise the findings across all of India. The included studies were concentrated in the wealthier Southwest of India, and there was only one study in the far North or Northeast.30 Future CHW studies should include these poorer states where the scarcity of health workers is higher and CHWs have greater potential to fill deficiencies in health needs.

Comparisons between studies were difficult because they were highly heterogenous. Even studies on the same disease had different designs and measured different outcomes. Differences included duration, target group, CHW education level, CHWs training duration, and content.

Only published peer-reviewed articles in English were included, which could have resulted in publication bias. It is likely that CHW programs have been documented in grey literature but not peer-reviewed literature; however, this review sought to maximise study and data quality by excluding grey literature.

Quality assessment found that many studies provided insufficient CHW training and intervention details for trial replication. To ensure replicability of the CHW interventions it is recommended that future papers are explicit about the training program contents and the community education that CHWs actually provided. Specifying the dates and locations of the trial, who selected the participants, the characteristics of patients lost to follow-up, and potential adverse effects is also recommended.

There is weak to moderate evidence to suggest that CHWs can be effective in helping in the management of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and oral cancer in low-resource settings in India; however, the evidence is limited by the number of studies and states of India which were represented in studies found by the review. Additionally, most studies provide little or no detail on the training methods, training content, and, importantly, remuneration of CHWs, which is known to affect worker output. Future studies in other Indian states and in other NCDs are required to provide more complete evidence on the effectiveness of CHWs in targeting NCDs in India.

| Search number | Search strategy |

| 1 | (anganwadi worker* OR ASHA* OR auxiliary health worker* OR barefoot doctor* OR community health advisor* OR community health advocate* OR community health aide* OR community health representative* OR community health worker* OR CHW* OR family health promoter* OR lay health advisor* OR lay health worker* OR non-physician health worker* OR volunteer health educator* OR volunteer health worker* OR village health worker*) AND India |

| Search number | Search strategy |

| 1 | Anganwadi worker* |

| 2 | ASHA* |

| 3 | auxiliary health worker* |

| 4 | community health advisor* |

| 5 | community health advocate* |

| 6 | community health aide* |

| 7 | community health representative* |

| 8 | community health worker* |

| 9 | CHW* |

| 10 | family health promoter* |

| 11 | lay health advisor* |

| 12 | lay health worker* |

| 13 | non-physician health worker* |

| 14 | volunteer health educator* |

| 15 | volunteer health worker* |

| 16 | village health worker* |

| 17 | 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12 OR 13 OR 14 OR 15 OR 16 |

| 18 | India |

| 19 | 17 AND 18 |

| Search number | Search strategy |

| 1 | Anganwadi worker* |

| 2 | ASHA* |

| 3 | auxiliary health worker* |

| 4 | community health advisor* |

| 5 | community health advocate* |

| 6 | community health aide* |

| 7 | community health representative* |

| 8 | community health worker* |

| 9 | CHW* |

| 10 | family health promoter* |

| 11 | lay health advisor* |

| 12 | lay health worker* |

| 13 | non-physician health worker* |

| 14 | volunteer health educator* |

| 15 | volunteer health worker* |

| 16 | village health worker* |

| 17 | 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12 OR 13 OR 14 OR 15 OR 16 |

| 18 | India |

| 19 | 17 AND 18 |

| Search number | Search strategy |

| 1 | Anganwadi worker* |

| 2 | ASHA* |

| 3 | auxiliary health worker* |

| 4 | community health advisor* |

| 5 | community health advocate* |

| 6 | community health aide* |

| 7 | community health representative* |

| 8 | community health worker* |

| 9 | CHW* |

| 10 | family health promoter* |

| 11 | lay health advisor* |

| 12 | lay health worker* |

| 13 | non-physician health worker* |

| 14 | volunteer health educator* |

| 15 | volunteer health worker* |

| 16 | village health worker* |

| 17 | 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12 OR 13 OR 14 OR 15 OR 16 |

| 18 | India |

| 19 | 17 AND 18 |

| Author | Year | Type of CHW | CHW Age | CHW Gender | CHW Education | Gov*/ Non-Gov | Training | Incentive/ Payment |

| Tian et al26 | 2015 | Volunteer community members | - | - | - | Non-government | 1 day, refresher every 3-4 mo | $US500 over 1 year |

| Xavier et al27 | 2016 | CHW | - | - | Yr. 10-12 | Non-government | 5 days | “modest salary”- not specified |

| Sharma et al28 | 2016 | Trained non-physician health worker | - | Mixed | Finished Yr. 12 | Non-government | 3 days | - |

| Kar et al29 | 2008 | Non-physician health worker | - | 4 male, 4 female | - | - | 4 days + monthly day refresher | - |

| Khetan et al30 | 2019 | CHW | - | - | - | -- | - | |

| Balagopal et al31 | 2008 | Trained science graduates | - | - | University Graduate | Non-government | 6 months | - |

| Balagopal et al32 | 2012 | CHW | - | - | . Yr. 12 | Non-government | 4 weeks | - |

| Sankaranarayanan et al33 | 2005 | Non-medical graduates | - | - | University Graduate | - | - | - |

| Jain et al34 | 2018 | CHW | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Shet et al35 | 2019 | Anganwadi worker/ Lay Health Worker | - | - | - | Government | - | - |

* Government employed

| Author | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Tian et al26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Xavier et al27 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sharma et al28 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kar et al29 | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Khetan et al30 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Balagopal et al31 | Y | Y | Y | N | - | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Balagopal et al32 | Y | N | Y | N | - | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sankaranarayanan et al33 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Jain et al34 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Shet et al35 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Author | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | QS |

| Tian et al26 | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | 25 |

| Xavier et al27 | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | 22 |

| Sharma et al28 | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | 23 |

| Kar et al29 | - | N | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | N | Y | Y | 17 |

| Khetan et al30 | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | 22 |

| Balagopal et al31 | - | - | - | - | Y | Y | - | - | - | - | - | N | Y | 14 |

| Balagopal et al32 | - | - | - | - | N | Y | - | - | - | - | - | N | Y | 12 |

| Sankaranarayanan et al33 | - | N | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | N | N | 19 |

| Jain et al34 | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | N | Y | 22 |

| Shet et al35 | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 20 |

Y = Yes, N = No, “-” = N/A, QS = Quality Score

| Author | 1c | 2a | 2b | 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | 4a | 4b | 4c | 4d | 4e | 4f | 4g | 4h |

| Balagopal et al31 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Balagopal et al32 | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Author | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 7 | 8a | 8b | 8c | 9 | 10a | 10b | 11a | 11b | 11c | 11d |

| Balagopal et al31 | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | - | Y | - | Y | - | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Balagopal et al32 | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | - | N | - | Y | - | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Author | 12a.i | 12a.ii | 12a.iii | 12a.vi | 12b | 13 | 14a | 14b | 14c | 14d | 15 | 16a | 16b | 17a |

| Balagopal et al31 | Y | Y | - | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | - | - | N | N | Y |

| Balagopal et al32 | N | N | - | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | - | - | Y | - | N |

| Author | 17b | 17c | 18 | 19 | 20a | 20b | 20c | 20d | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | Total |

| Balagopal et al31 | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 31 |

| Balagopal et al32 | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | 26 |

Y = Yes, N=No, “-” = N/A

1a. Information on how unit were allocated to interventions (Title and Abstract)

1b. Structured abstract recommended

1c. Information on target population or study sample

2a. Scientific background and explanation of rationale (Into)

2b. Theories used in designing behavioural interventions

3a. Eligibility criteria for participants, including criteria at different levels in recruitment/sampling plan (e.g., cities, clinics, subjects) (Method/Participants)

3b. Method of recruitment (e.g., referral, self-selection), including the sampling method if a systematic sampling plan was implemented

3c. Recruitment setting

3d. Settings and locations where the data were collected

4a. Content: what was given? (Methods/intervention)

4b. Delivery method: how was the content given?

4c. Unit of delivery: how were the subjects grouped during delivery?

4d. Deliverer: who delivered the intervention?

4e. Setting: where was the intervention delivered?

4f. Exposure quantity and duration: how many sessions or episodes or events were intended to be delivered? How long were they intended to last?

4g. Time span: how long was it intended to take to deliver the intervention to each unit?

4h. Activities to increase compliance or adherence (e.g., incentives)

5. Specific objectives and hypotheses (Method/Objectives)

6a. Clearly defined primary and secondary outcome measures (Method/Outcomes)

6b. Methods used to collect data and any methods used to enhance the quality of measurements

6c. Information on validated instruments such as psychometric and biometric properties

7. How sample size was determined and, when applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping rules (Method/Sample size)

8a. Unit of assignment (the unit being assigned to study condition, e.g., individual, group, community) (Method/Unit of Assignment)

8b. Method used to assign units to study conditions, including details of any restriction (e.g., blocking, stratification, minimization)

8c. Inclusion of aspects employed to help minimize potential bias induced due to non-randomization (e.g., matching)

9. Whether or not participants, those administering the interventions, and those assessing the outcomes were blinded to study condition assignment; if so, statement regarding how the blinding was accomplished and how it was assessed. (Method/Masking)

10a. Description of the smallest unit that is being analysed to assess intervention effects (e.g., individual, group, or community) (Method/Units of Analysis)

10b. If the unit of analysis differs from the unit of assignment, the analytical method used to account for this (e.g., adjusting the standard error estimates by the design effect or using multilevel analysis)

11a. Statistical methods used to compare study groups for primary methods outcome(s), including complex methods of correlated data (Method/Analysis)

11b. Statistical methods used for additional analyses, such as a subgroup analyses and adjusted analysis

11c. Methods for imputing missing data, if used

11d. Statistical software or programs used

12a.i Flow of participants through each stage of the study: enrolment, assignment, allocation, and intervention exposure, follow-up, analysis (a diagram is strongly recommended) (Results/Participant Flow)

12a.ii Enrolment: the numbers of participants screened for eligibility, found to be eligible or not eligible, declined to be enrolled, and enrolled in the study

12a.iii Assignment: the numbers of participants assigned to a study condition

12a.iv Allocation and intervention exposure: the number of participants assigned to each study condition and the number of participants who received each intervention

12a.v Follow-up: the number of participants who completed the follow-up or did not complete the follow-up (i.e., lost to follow-up), by study condition

12a.vi Analysis: the number of participants included in or excluded from the main analysis, by study condition

12b. Description of protocol deviations from study as planned, along with reasons

13. Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up (Results/Recruitment)

14a. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in each study condition (Results/Baseline data)

14b. Baseline characteristics for each study condition relevant to specific disease prevention research

14c. Baseline comparisons of those lost to follow-up and those retained, overall and by study condition

14d. Comparison between study population at baseline and target population of interest

15. Data on study group equivalence at baseline and statistical methods used to control for baseline differences (Results/ Baseline equivalence

16a. Number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis for each study condition, particularly when the denominators change for different outcomes; statement of the results in absolute numbers when feasible (Results/ Numbers Analysed)

16b. Indication of whether the analysis strategy was “intention to treat” or, if not, description of how non-compliers were treated in the analyses

17a. For each primary and secondary outcome, a summary of results for each estimation study condition, and the estimated effect size and a confidence interval to indicate the precision (Results/ Outcomes and Estimations)

17b. Inclusion of null and negative findings

17c. Inclusion of results from testing pre-specified causal pathways through which the intervention was intended to operate, if any

18. Summary of other analyses performed, including subgroup or restricted analyses, indicating which are pre-specified or exploratory (Results/Ancillary Analysis)

19. Summary of all important adverse events or unintended effects in each study condition (including summary measures, effect size estimates, and confidence intervals) (Results/Adverse Events)

20a. Interpretation of the results, taking into account study hypotheses, sources of potential bias, imprecision of measures, multiplicative analyses, and other limitations or weaknesses of the study (Discussion/Interpretation)

20b. Discussion of results taking into account the mechanism by which the intervention was intended to work (causal pathways) or alternative mechanisms or explanations

20c. Discussion of the success of and barriers to implementing the intervention, fidelity of implementation

20d. Discussion of research, programmatic, or policy implications

21. Generalizability (external validity) of the trial findings, taking into account the study population, the characteristics of the intervention, length of follow-up, incentives, compliance rates, specific sites/settings involved in the study, and other contextual issues (Discussion/Generalisability)

22. General interpretation of the results in the context of current evidence and current theory (Discussion/Overall Evidence)

23. Registration number and name of trial registry (other info)

24. Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available (other info)

25. Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders (other info)

| Author’s Name | 1a | 1b | 2a | 2b | 3a | 3b | 4a | 4b | 5 | 6a | 6b | 7a | 7b | 8a | 8b | 9 |

| Tian et al26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | N | Y | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y |

| Xavier et al27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | N | N | Y | - | N | - | Y | Y | Y |

| Sharma et al28 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | N | N | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kar et al29 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | N | Y | N | N | - | N | - | Y | Y | N |

| Khetan et al30 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | N | Y | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y |

| Sankaranarayanan et al33 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | N | N | - | Y | N | N | Y | N |

| Jain et al34 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | N | Y | - | Y | - | Y | N | N |

| Shet et al35 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | N | Y | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y |

| Author’s Name | 10 | 11a | 11b | 12a | 12b | 13a | 13b | 14a | 14b | 15 | 16 | 17a | 17b | 18 | 19 |

| Tian et al26 | N | N | - | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | - | N |

| Xavier et al27 | Y | N | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | - | N |

| Sharma et al28 | N | Y | - | Y | - | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | - | N |

| Kar et al29 | Y | N | - | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | - | N |

| Khetan et al30 | N | N | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | N |

| Sankaranarayanan et al33 | N | N | - | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Jain et al34 | Y | N | - | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | N |

| Shet et al35 | Y | Y | - | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | - | - | N |

| Author’s Name | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | Total |

| Tian et al26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 25 |

| Xavier et al27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 23 |

| Sharma et al28 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 22 |

| Kar et al29 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 19 |

| Khetan et al30 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 27 |

| Sankaranarayanan et al33 | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | 18 |

| Jain et al34 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 20 |

| Shet et al35 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 28 |

Y = Yes, N=No, “-”=N/A

1a. Identification as a randomised trial in the title (Title and Abstract)

1b. Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions (for specific guidance see CONSORT for abstracts)

2a. Scientific background and explanation of rationale (Introduction)

2b. Specific objectives or hypotheses

3a. Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial) including allocation ratio (Methods/Trial Design)

3b. Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility criteria), with reasons

4a. Eligibility criteria for participants (Methods/Participants)

4b. Settings and locations where the data were collected

5. The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered (Methods/Interventions)

6a. Completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed (Methods/Outcomes)

6b. Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons

7a. How sample size was determined (Methods/Sample Size)

7b. When applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines

8a. Method used to generate the random allocation sequence (Methods/Randomisation/Sequence)

8b. Type of randomisation; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size)

9. Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned (Randomisation/Allocation concealment mechanism)

10. Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions (Methods/Randomisation/Implementation)

11a. If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how (Methods/Blinding)

11b. If relevant, description of the similarity of interventions

12a. Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes (Methods/Statistical Methods)

12b. Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses

13a. For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analysed for the primary outcome (Results/Participant Flow)

13b. For each group, losses and exclusions after randomisation, together with reasons

14a. Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up (Results/Recruitment)

14b. Why the trial ended or was stopped

15. A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group (Results/Baseline data)

16. For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups (Results/Numbers Analysed) Y

17a. For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval) (Results/Outcomes and Estimation)

17b. For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended

18. Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing pre-specified from exploratory (Results/Ancillary analysis)

19. All important harms or unintended effects in each group (for specific guidance see CONSORT for harms) (Results/Harms)

20. Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses (Discussion/Limitations)

21. Generalisability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings (Discussion/Generalisability)

22. Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence (Discussion/ Interpretation)

23. Registration number and name of trial registry (Other information/Registration)

24. Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available (Other information/Protocol)

25. Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders (Other information/funding)