Figure 1. The Spread of the H1N1 Influenza Virus in Africa in 1918

REVIEW ARTICLE

Omololu Ebenezer Fagunwaa

a MTh, PhD (Theology), Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria, and PhD(c) (Microbiology), University of Huddersfield, UK

Infectious outbreaks that lead to epidemics and pandemics are dreaded because of the adverse health, economic, and social effects. The 1918 pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza virus killed about 40 million people worldwide. Like the case of COVID-19, the pandemic of 1918 kept Christians, as well as people of other faiths, from worshipping together. However, African indigenous Pentecostal movements and groups emerged in various parts of the continent around the same time. This period was the time of huge Pneumatic experience and spiritual awakening. Pentecostals devoted themselves to building their faith and praying ceaselessly during that time, and this has become the foundation of the doctrine and theological instruction of most African-initiated churches (AICs). Because there have been no studies that consider the 1918 flu pandemic and Pentecostal response in Africa, this study was undertaken. The time of the 1918 pandemic appeared to be a good opportunity for spiritual awakening. Intense prayer prevailed during those times, and teaching and exposition about prayer formed the core of the theology of most AICs. Pandemics often bring devastation but could also be an opportunity for spiritual awakening through prayer, love in action, social justice, compassion, and care.

Keywords: Influenza, Pentecostals, Practical Theology, COVID-19, Pandemic, Christian, Africa

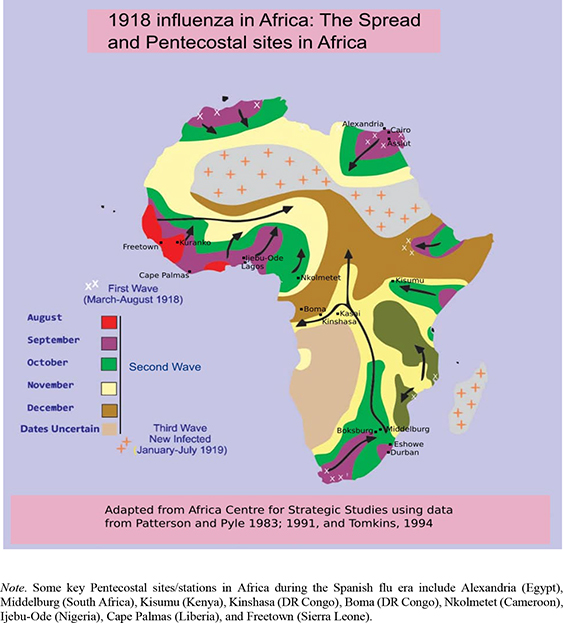

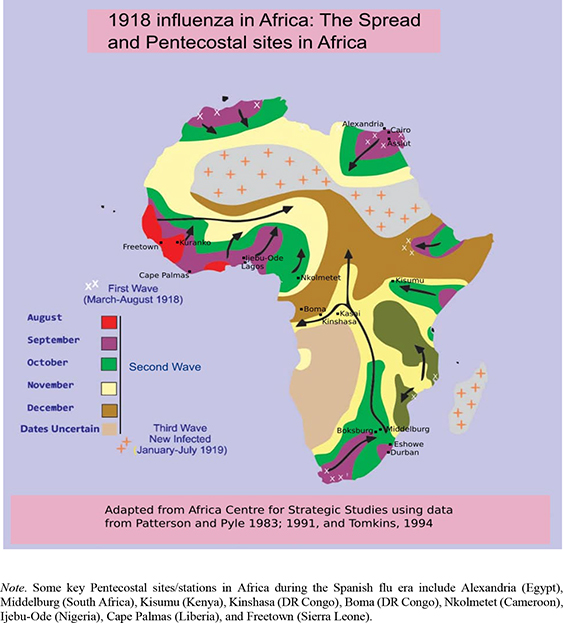

In 1918, the entire world was overwhelmed with a viral infection caused by a new strain of influenza virus and characterised by three waves.1,2 Africa had its large share during the deadly second wave (Aug–Dec 1918), and the simultaneous third wave (Jan–Jul 1919). In the West Coast of Africa, the spread of the infection started in August, in a Dakar, Freetown, and Accra, then spread to Lome, Lagos, and Calabar. In September 1919, the pandemic broke out in Douala, and in October of the same year, it reached Libreville and Equatorial Guinea (Figure 1). Ultimately, the disease killed 40 million people globally, and a conservative estimate of the mortality in the African continent was 1.4 million.1,2 The 1918 influenza pandemic dispensation which overlapped with the move of the Holy Spirit in the life of indigenous African Christians. Many may believe Pentecostalism was brought into Africa and imposed on its people by Western missionaries, but a persuasive argument founded on historical accounts reveals that such a premise is untrue in many countries. African Pentecostalism is very organic in nature, distinctly African, and never imported.3 We will focus our analysis on two African countries, Kenya and Nigeria, although Pentecostal movements have also become well established in Liberia, Sierra Leone and South Africa. South Africa was the African country most affected by the 1918 influenza pandemic, and religious beliefs have been reported to be responsible for the high fatality rate.4,5 Due to the diversity and complexity of Pentecostal movements at that time and the pandemic’s devastation in South Africa, an analysis of this country’s experience should form a separate academic discourse. Pandemics, like the current COVID-19, bring an array of health, economic, and social disruptions. The devastations renders people helpless, and it becomes difficult to see anything other than fear and evil. However, history, which studies the past and the legacies of the past in the present is essential for “rooting” people and events in time. One of the historic moments in the life of African Pentecostalism was the 1918 influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 virus. However, no study has narrated the pandemic with a focus on Pentecostal events in Africa. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to discuss how Pentecostalism was facilitated in Nigeria and Kenya despite the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. Also presented are the Pentecostal/ Charismatic activities and events during the time and their implications for COVID-19.

Kenya has unique indigenous as well as missionary Pentecostal stories around the period of discussion. Nigeria is also worth considering as the 1918 flu pandemic coincides with the organic indigenous Pentecostal formation in the country. First, a literature search was conducted in Google Scholar, BASE, CORE, and Semantic Scholar to see if there has been any previous study that addressed the study aim. To discuss the Pentecostal historic activities and the response at the time of the 1918 pandemic, scholarly documents were reviewed and resource materials in the Pentecostal Archive were explored. (https://pentecostalarchives.org/) The Pentecostal Archive is a consortium of Pentecostal collections managed by the General Council of the Assemblies of God to make global Pentecostal resources accessible from 1897 to the current day. An additional search was conducted on Dimensions (https://www.dimensions.ai/), a database that linked data and documents in a single platform. Publication dates start from the year 1665 and the platform has over 168,000 published documents for the 1918–1920 period. A further localised, in-depth search was conducted on old digitalized African newspapers using a trial version of the NewsBank/Readex collection. (https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex). Readex provides an acclaimed primary source of a collection of essential material, including newspapers from all around the globe. The digital African newspaper collections cover the period between 1835–1925. The keywords used on all the electronic databases included “Kenya,” “Nigeria,” “Kisumu,” “Mombasa,” “Lagos,” “Ijebu Ode,” “Influenza,” “Plague,” “Virus,” “Spanish flu,” “Flu,” “Pentecost,” and “Heal.” The location keywords helped to identify the main Pentecostal figures and events. The search was initially done broadly to cover materials available in the database between 1897–2020 to get an overview of events and manuscripts relevant to this study. Next, a filtered search was conducted for the years 1915–1925 to accurately narrate events relating to the 1918 pandemic. Where the main events and persons were identified, a narrower search was conducted using the names and locations that were mentioned in a specific storyline or event.

Figure 1. The Spread of the H1N1 Influenza Virus in Africa in 1918

The examination in academic databases showed that there was no previous study that addressed the aim of this study. Hence this is premier scholarship on the subject of African Pentecostalism and the 1918 flu pandemic. Pentecostalism in Kenya had two independent histories, one was through missionaries and the other was an organic emergence among the natives in Western Kenya. The 1918 flu epidemic started during the “silent period” in Kenya with little engagement from the Pentecostals. The only related account shows that the Kellers (Pentecostal missionaries) were faithful and showed genuine concern and care for the indigenous population the Lord had entrusted to them. In Nigeria, a faith-healing preacher, Garrick Braide, was restricted from performing healing, but another charismatic group sprang up within the Anglican Church in the Southwest of the country. Different spiritual activities that characterised the response of the Pentecostal movement to the pandemic were the bold application of faith, fervent prayers, and faithful expectations of supernatural healing based on the Word of God when all medicines, and vaccines failed. The findings of the research will focus on several representative key people and movements within this period of time in Kenya and Nigeria.

Kenya is an East African country along the Indian Ocean, sharing a long border with Tanzania, Somali, Ethiopia, and Uganda. Christianity can be first traced to the Portuguese (Catholic) and then the British (Anglican) colonization. Two factors dramatically changed Christianity in Kenya—Pentecostalism and the emergence of African-initiated churches (AICs).6 We will discuss two origins of Pentecostalism in Kenya and their relationship with the 1918 pandemic.

Kenya’s earliest Pentecostal history can be traced to Clyde Toliver Miller (1884–1954) and his wife, Lila May Sturgis (1891–1978). Lila was a daughter of Miller’s mentor, Robert Waldron of Kansas. In 1907, the couple left for Kisumu, Kenya, to work with the Nilotic Independent Mission. At the initiative of Miller, Robert Waldron and John Buckley (a mission financier) quickly formed the “Apostolic Faith Mission” to acquire 109 acres of mission land among the Nyangori people in Kisumu.7 However, in 1908, the parcel of land was bought by Clyde Miller in his name, and that led to stewardship disagreements with the sponsors8 and a consequent marital separation from Lila7 that was responsible for the collapse of Clyde Miller’s mission. What can we say about Miller during the influenza pandemic? The time of pandemic was a frustrating period for Clyde Miller as he struggled with divorce, disfavour with the government, and distrust from his sponsor. So, in 1919, he sold the mission field to a “fill-in” German missionary, Otto Keller (1888–1942), of Pentecostal Assemblies Mission.9 Miller’s ministry could not stand the test of the pandemic. It appeared as if God used the pandemic to repair and reposition His Church. The absence of the Millers names in the list of missionaries in the minutes of the 7th General Council of the Assemblies of God held in 1919 and the appearance of Mr and Mrs John Buckley as missionaries in British East Africa confirmed the decline of Clyde Miller’s missionary work.10

For Otto Keller, the active years of the pandemic were a time of conjugal union with another missionary (Marion Wittich), preparation for mission work, and childbearing.9 However, based on missionary records, we have placed the Keller’s marital union a year after the pandemic in 1920.11,12,13,14 Records relating to missionary activities during the pandemic about the new Kenya Pentecostal leaders, Mr and Mrs Keller, especially Marion Keller, in 1919, gave testimonies about new converts, powerful evangelization, supernatural protection, and personal provision during her long journey from Nyangori to Detroit during World War 1.11,12

We also assumed that Marion was already in Detroit by September 1918. She wrote in May 1919: “I am more determined to go back to Africa now than ever before. I have been home for only nine months and am longing to get back.”11 So, we now know why there was a “silence” about the epidemic in Kenya. An editor (unnamed) in The Latter Rain Evangel magazine of September 1920 wrote:

Mrs. Marion Wittich, who married Mr Keller soon after returning to East Africa, was unable to return to her old station owing to certain restrictions regarding German East Africa, so she and her husband are on a station at Kisumu, formerly occupied by Clyde Miller. Mr Keller has been in East Africa for some years but previously to this time he has not been entirely engaged in the Lord’s work. He is now busy doing some personal work among the Nyangori tribe, who have never had the gospel nor a missionary among them.13

It is assumed that Clyde Miller may not have been a dependable Pentecostal voice to respond to the 1918 flu in Kenya. More so, using the keywords “Clyde,” “Toliver,” “Miller” between the years 1917–1922 in the consortium database did not yield any remarkable account of his engagement/response during the pandemic nor engagement with the mission sponsors. However, a search between 1913 and 1916 indicated that Clyde Miller wrote letters from Nyangori, Kisumu, Kenya;15,16 received permission to stay at his post in Kisumu;17 and wrote about the lack of funds.18 Why was there not an adequate hint or correspondence about the 1918 influenza from both the Millers and the Kellers, especially at a time when various Pentecostal magazines, such as International Pentecostal Holiness Advocate, Pentecostal Herald, Pentecostal Evangel, Church of God Evangel, and Latter Rain Evangel were reporting the pandemic?

A search using “Keller” and “Kisumu” for the years 1918–1919 in the Pentecostal Archive did not give any result. The only appearance in 1920 was concerning the bimonthly missionary report/disbursement and Mrs Keller’s September letter mentioned earlier. After 1920, the Kellers had many correspondences and featured articles in the Pentecostal Archive which further support our claim about the year of marriage and “silence” during the pandemic. This also attests to the success of their missionary work in Kenya. It is worth mentioning that some years after the pandemic, the Kellers trained and sponsored Kivuli Zakayo, a man who became a prominent indigenous figure in Kenyan Christian history.19 Again, the repositioning of the church from greedy Miller to faithful Keller after the pandemic yielded long-lasting positive results. The COVID-19 pandemic could also bring repair and repositioning for Pentecostalism, specifically, and Christianity, in general. About the Kellers, we inferred that they had experiential knowledge of a wave of the plague, perhaps between late 1919 and early 1920, at Nyangori. Marion Keller wrote:

Mr Keller has much fever. The morning of the baptismal service he had a high fever and had to trust God to keep him as he went into the water, which He did. Plague has been raging in this part of the country and has taken three of our best girls. We still have twenty-five girls and twenty boys. So you see what a family we have to care for.14

Some five years after the plague, Mr Keller wrote an article about the zeal of Africans to spread the gospel. This was published in the Latter Rain Evangel and The Bridegroom’s Messenger with an extract: “… the opportunity in Africa is greater [than] was ever known before in the history of the Church. In the last six years since the close of the war, practically that whole country is open to the Lord Jesus Christ.”20 It was presumed that the pandemic must have opened the hearts of African peoples to the gospel.

The Roho (Spirit) movement is another Pentecostal element in Kenya but it was inactive during the pandemic. The movement commenced in 1912 when the Spirit struck a group of Church Mission Society (CMS) converts being led by Jeremiah Otanga, a catechist and elder within the Anglican church in Ruwe, Western Kenya. The Roho activities had been interrupted by World War 1. In 1933, Alfayo Odongo Mango (1884–1934) and Lawi Obonyo (c1911–1934) reorganised the movement again.21 Hoehler-Fatton’s book Women of Fire and Spirit relates the extensive narrative of Roho congregations as a means of preserving the Roho ancient religious history. Hoehler-Fatton documented oral testimonies of the working of the Spirit and devotion to prayers by this group during the early years (1912–1915). Thereafter, the group was scattered, and then Alfayo Mango (who was born and died in Musanda) was possessed of the Spirit in 1916. Despite the rise of the new leader and his numerous religious and socio-political activities, as documented by Hoehler-Fatton, there was no mention of the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919. This is an indication of the non-involvement of the organisation in the problem of the pandemic.

Ruwe is near Musanda, and both are about 60 km away from Nyangori, Kisumu. The three historic Kenya Pentecostal sites are each about 900 km away from Mombasa, the entry point of the influenza virus. The historic Pentecostal towns of Ruwe, Musanda, and Nyangori, Kisumu are in the Western regions of Kenya and are considered hinterlands, without good administrative and health records.22 Yet, there are reports that every district in Kenya was struck by the devastating effects of influenza, even in sparsely populated regions.23 In Kenya, the chronicles from the Roho spiritual authorities did not suggest any experience of the pandemic,21 though the Pentecostal missionary, Marion Keller, mentioned a plague in her 1920 letter.

Nigeria is a West African country along the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean. It shares a long border with Cameroon, Niger, and the Benin Republic. Christianity came to the country in the 15th century through Catholic Portuguese monks but became prominent with the establishment of the Church of England mission field in 1842.24 Here, also, we will discuss Pentecostal history in Nigeria and the connection with the 1918 pandemic. It is worth noting that the Pentecostal Archive holds no records about the epidemic in Nigeria because all foreign Pentecostals in Nigeria arrived at their establishments after 1918. This includes the Welsh Apostolic Church (1931), the Assemblies of God (1939), and the Foursquare Gospel Church (1954).25 However, there is a body of documents and history from the indigenous Pentecostal movement that are worth exploring.

An Anglican sexton, Daddy Ali (probably a nickname) of St. Saviours Church, Ijebu Ode, Southwestern Nigeria was guided in dreams to form a prayer group during the influenza epidemic of 1918.26,27 Other prominent founding fathers within the Anglican church were E.O. Onabanjo, D.C. Oduga, E.O.W. Olukoya, and J.B. Shadare, who later became the core leader of the movement. The group (later known as the Precious Stone or Diamond Society) devoted themselves to prayer and shielded themselves from “calamity that would befall the Anglican church”.27,29 The “desperate situation” during a disease outbreak where there is no potent medicine, made the people attribute the pandemic to God’s chastisement.26 A Pew Research survey report of Nigerian Pentecostals stated that the Precious Stone Society (Aladura) was formed to heal influenza victims.25 However, such an assertion does hold a popular view in notable historical accounts by members of various churches and the movement itself. We note that the formation of the Aladura movement was informed by the revelation received by Daddy Ali, which emphasized devotion to prayers. It is presumed that prayers were targeted at the healing of influenza victims and mitigating the raging of World War 1.28

The Aladura group was formed during the global 1918 pandemic, but more likely before Nigeria had her share of the epidemic, hence the group formation may be placed at a date before September/October 1918. Our inference is that influenza was introduced in September through rapid local transmission (as discussed later), a considerably longer time after Daddy Ali fore-warned (in at least two separate visions) of impending “calamity.”27 Daddy Ali’s warnings would not be considered divine revelation if the “calamity” was already established. Fatokun states:

The prayer group continued her activity in Anglican Parish, which was basically “prayer.” However, there was an event which promoted the group from a prayer group to a prophetic-healing movement. In the same year (1918), an epidemic (variously described as smallpox and bubonic plague) struck in every part of the world just during the closing month of the First World War.”29

During the epidemic, a prophetic icon was reportedly healed of influenza. A 19-year-old member of the prayer group, Sophia Odunlami (later named Mrs Ajayi), claimed to have a spiritual experience while sick of influenza virus for five days. She claimed to hear a voice:

“I shall send peace to this house and the whole world as the world war is ended.”

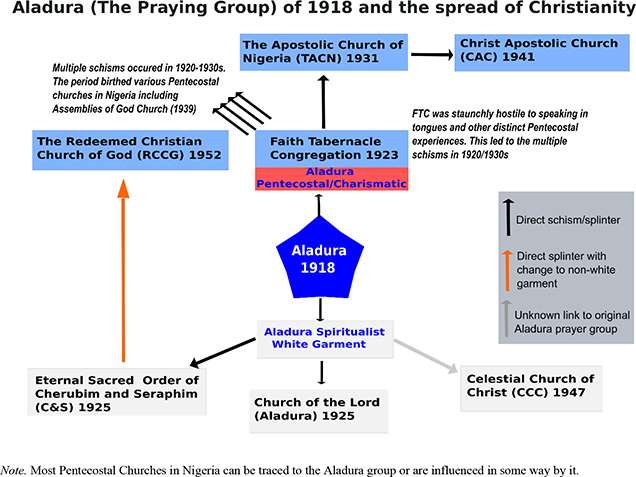

The young prophetess claimed that rainwater and prayer would be the most effective remedy for the influenza victims and itinerantly preached against the use of any form of medicine (both traditional and western) as a remedy to the illness and often used Zachariah 14 as her favourite biblical text.29 We assumed her stern warning must have placed more emphasis on verses 11–20 because this part of the text is plague related. Zachariah 14 is not an uncommon text used within the puritan/holiness movement which tags such verses as “The Day of the Lord” and “Holiness unto the Lord.” Prophetess Sophia Odunlami was dubbed, “a God-gifted divine leader raised in an outbreak of influenza against which all charms and medicines had been useless.”29 Though no verifiable evidence of her healing of influenza victims was found, one cannot infer that influenza victims were never healed. As Pentecostal adherents, who have personally experienced supernatural healing, we suggest that we should document evidence of healing in the 21st century wherever possible. Another member of the group was Moses Tunolase Orimolade, and he operated in the healing ministry. Anderson stated that, “Crowds came to him for prayer for healing during the influenza epidemic of 1918.”30 It is an established record that the Aladura prayer movement devoted themselves to prayers, longed to experience the supernatural, and spread the “supernatural” gospel, at least throughout Nigeria, especially in Yoruba land (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Aladura of 1918 and the spread of Christianity

Let us now consider the response of the prayer group leader to the pandemic. Some months after the prayer group had been formed, the famous St. Saviours’ (Anglican) Church complied with a government order of “lockdown” just like other churches. The colonial government, in a bid to limit the spread of the pandemic, ordered all public buildings to be closed down. The vicar-in-charge complied with this government order. His action was interpreted as an act of faithlessness by the Aladura prayer group. The group resorted to intensive prayers, church members held a procession around Ijebu Ode town, and made prayers for deliverance.29 We think that it is important for Christians to abide with constituted authorities’ efforts to break the chain of infection during epidemics. Though the church was closed, it appeared praying and prophetic-healing activities remained very active. Fatokun further reported:

With the closure of the church, this group continued relentlessly in its praying and prophetic-healing activities with the venue of the meeting shifting to the front of their closed church and later in the house of the People’s Warden and lay member of the Lagos Diocesan Synod, Mr J.B. Sadare. It was at this juncture that J.B. Sadare’s name became prominent as the leader of the group.29

It was reported that the Bishop of Lagos, The Rt. Rev. Melville Jones, praised the high morality of the Precious Stone Society for its persistence in prayers and demonstrations of the power of God, but objected to its insistence on the exclusive use of faith healing, its opposition to the baptism of infants, and its reliance on dreams and visions for guidance.29 Two years after the end of the influenza plague, a spiritual-medical argument ensued at the 1922 Lagos Synod meeting. Shadare, the prayer group leader, had refused to have his children baptised. He argued that infant baptism was wrong, and the Lord had prevented him from doing so through a vision. However, the Assistant Bishop of Lagos, Isaac Oluwole, tried to debunk this claim against infant baptism. Oluwole said the group was not oblivious of the fact that the pandemic was not eradicated, and children had little or no resistance against the virus, which made it quite common for children to die. Such differences between the mainstream Anglican church and the Aladura prayer group caused a separation and led to the beginning of a new era in Nigeria: the Charismatic/Pentecostal movement.29 Ayegboyin and Ishola’s epidemic report revealed:

This epidemic, coupled with the economic depression that followed, had adverse effects on the Church. Most public institutions such as the schools, hospitals, clinics, and offices, as well as some Churches, were closed by the colonial administrators. A good number of Europeans returned home and not a few missionaries abandoned their congregation to heed the call to go back to their countries. Several churches were without ministers and spiritual matters seemed to be fading into oblivion.”31

There was confusion, and many Christians attempted to go back to the traditional religion, but a few committed Christians engaged in a more practical approach to solving the prevailing problems through devotion to family worship, personal prayers, and small gatherings for prayer.

Another unforgettable encounter that occurred during the crisis of the 1918 pandemic was the incident that took place in the Niger Delta region of the country through Garrick Sokari Braide (1882–1918). Braide was an Anglican catechist and was committed to evangelism and healing ministry. He preached against alcohol and idolatry prominently between 1914–1918.32,3,33 At the peak of Braide’s ministry, there was a feud between him and the Assistant Bishop of the Niger Delta and Benin territories—Dr James Johnson (c1836–1917). This culminated in two imprisonments of Braide by the colonial government, and he died some months after his release in 1918.31,32,34,35 Clearly, Braide’s ministry did not enjoy the support of the missionaries or the colonial government. Did Braide’s healing ministry help during the 1918 pandemic? Braide’s healing ministry after his 1918 release from prison is not well documented, but he is unlikely to have performed a healing for influenza victims if he died before October 1918 since community transmission increased around October/November 1918. More so, after his release in 1918, the healing ministry of Garrick Braide was restricted, if not suppressed. His ministry suffered and went into total oblivion. Ludwig states: “When Braide returned from prison in early 1918, the chiefs of Bakana forbade him [from] practising healing by faith on the same scale as before.”32

The epidemiological timeline also supports our speculation that Braide was unlikely to have made a healing response to the flu epidemic. In mid-September 1918, the government health authorities dispatched a telegram that declared influenza as an infectious disease and immediately put in force quarantine measures at all ports and shores. On 30th August, the Governor of Sierra Leone transmitted via cablegram to the Lagos colony the seriousness of the pandemic.36,37,38 On 14th September, three vessels (SS Panayiotis, S.S. Ashanti, and SS Bida) arrived at Lagos carrying already infected people. There was no “test and trace” system for those aboard, though symptomatic passengers were hospitalised or quarantined, and the ships disinfected and quarantined.37 Tomkins noted that “of all the West African colonies, Nigeria organized the most thorough measures, partly because warnings from Sierra Leone and the Gambia had enabled administrators to plan.”38 Ohadike, in 1991, published his work using colonial records that documented additional cases reported in the ocean liners S.S. Ravenston at Port Forcados (on 27th September) and S.S. Batanga at Calabar (28th September).39 Isolated cases of person-to-person transmissions continued until 15th November when a sudden upsurge with hundreds of cases was observed. Other transmission routes, such as boat and rail systems (the major means of transportation), were implemented, and by December 1918, the infectious disease was spreading throughout Nigeria. From a population of 17,690,936, the number of deaths was recorded at 454,988, hence the death rate was 2.6%.39 An account by Ogunewu and Ayegboyin noted that—“He was finally released in 1918 but died shortly thereafter in November of that year.”40 The authors, however, did not state any supporting reference or inference by oral narrative or other means. Braide’s death is more complex according to Anderson’s account, which assumes that Braide died perhaps of influenza.30 Could the healing minister die of influenza or by an accident? How Garrick died could form the theme of another discourse that this paper will not interrogate further. Again, we found no account of Braide healing victims of influenza.

Newspaper databases show no record of faith-healing from influenza performed by any Christian leader or a member of the Aladura. If many healings only through prayers had happened, it would have been a regular feature in the newspapers. Likewise, there was no rebuttal of such healing or mention of it, and this suggests that a successful community-wide, faith-healing against influenza was very unlikely during the Spanish flu. An examination of local Nigerian newspapers indicates that there was an intensive, bi-weekly advertisement of “all-purpose, cure-all” tonics such as “Veno’s lighting cough cure” by The Veno Drug Co. Ltd, Manchester. Veno’s tonic was advertised as “the safest and surest remedy” for various upper and lower respiratory diseases including influenza.41 Another popular all-purpose medicine was “Phospsferine” by Ashton and Parson Ltd, London, which was advertised to have a worldwide reputation for curing influenza and other diseases speedily.42 By September 1918, many tonic products featured as the cure to influenza in advertisement pages of newspapers such as Lagos Standard, Nigerian Pioneer, and Lagos Weekly Record.41-44

However, during the 1918 influenza pandemic, all Western medicines, mainly produced in England, did not have favourable effectual standing among the locals. The plague also overwhelmed native herbalists, including the Muslim native herbalist’s society called “Ajo Aiye.”43 Hence, people resorted to prayer since there was no efficacious remedy from both Western and traditional medicines. A feature in the Lagos Weekly Record newspaper reminded the readers that the pandemic was predicted/ prophesied by Ode, as far back as February 1916, and the only remedy was, “a true and ardent prayer.”44 The call and devotion to prayer during the pandemic time accelerated the membership of the Aladura movement.

Aladura membership grew during and after the 1918 pandemic. In 1923, the Aladura entered a short-lived affiliation with the Faith Tabernacle Congregation of Philadelphia. Faith Tabernacle was introduced to the group by a member called David O. Odubanjo (a reader of Faith Tabernacle’s Sword of the Spirit magazine).29,45 Odubanjo joined the Aladura group in 1919 and soon became a very prominent leader. He later became the first general superintendent of Christ Apostolic Church, a splinter church of the Aladura group. Faith Tabernacle Congregation, or its magazine, did not influence the creation of the Aladura prayer group, though its faith-healing teachings appeared to strengthen the group.29,46 Noteworthy is that 1918 was a time of spiritual awakening, and Nigerian Pentecostalism emerged independently of “Pentecostal” missionaries if traced to Garrick Braide and the later prayer group—the Aladura movement.

Some Pentecostals believed only in the use of pray for supernatural healing during the 1918 influenza pandemic. However, we believe that such singular expectations of supernatural healing as the only solution directly undermines the blessings of God in nature (plants), as well as God’s character of answering prayers and meeting our human needs in different ways—including pharmaceutical discoveries. More so, the healing ministry of the church throughout the Bible is practised in four ways—prayer, word, touch, and “means”. There are several instances in which medical means are used in the scripture to provide healing; for example, the fig poultice prescription (2 Kings 20:7, Isaiah 38:21) and olive oil (Mark 6:13, James 5:14, 1 Tim 5:23). Prayer and faith still form the basis of Christian response to the healing of people in the time of sickness or even epidemics, but a far greater variety of means are available now than ever before. The means for us in this age include relatively safe and efficacious medicines and vaccines which should be taken with thanksgiving, prayer, and faith. Some authors mentioned that influenza victims were healed, though we found no primary reference for such an assertion. Testimonies of healing during this period of epidemic must be documented with verifiable pieces of evidence where possible. Overall, the period of the 1918 pandemic appears to be a time of great awakening in African Christianity—including the birth of indigenous Pentecostals, whose splinter churches are scattered all over the world with millions of members emphasizing the power of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

The 1918 influenza infectious outbreak was dreadful, but the supernatural occurred amid the fearful pandemic, and the church expanded. Kenyan and Nigerian Pentecostals were mostly divergent in their responses to the pandemic. Kenya’s Pentecostalism was inactive until closer to the end of the pandemic, while Nigeria birthed its Pentecostalism in the same year and responded via prayers, persistent Christian faith, and longing for supernatural intervention. Prayers still formed the basis of a Christian response to the healing of people in a time of sickness and pandemic, like the coronavirus pandemic that is raging presently. The approach for Christians during this COVID-19 pandemic may be leveraging on various communication technologies such as telephone, mobile phone, Zoom, Skype, Facebook, Whatsapp, and Tik-Tok to organise virtual prayers, praise, and healing services, and never to physically gather together in large numbers during times of increased viral reproduction or oppose government measures to bring the epidemic under control. These are actions of obedience and even greater faith which should not be perceived as spiritual weakness or faithlessness. The Church buildings may be closed but the Church community should remain open and connected via the technological means with which we are blessed. God has blessed us with a far greater variety of means now than were present in 1918. The means for us include technologies for sustaining the faith community in situations where there are physical restrictions and safe, efficacious medicines and vaccines (whenever available), which should be accepted with thanksgiving, prayer, and faith. Pandemics often bring devastation but could also be an opportunity for spiritual awakening through prayer, love in action, social justice, compassion, and care.