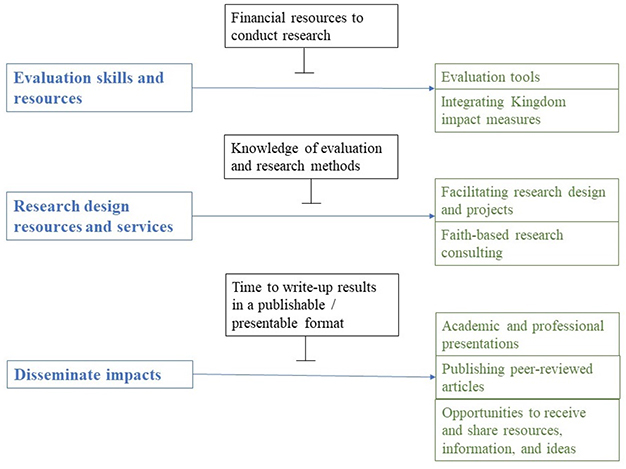

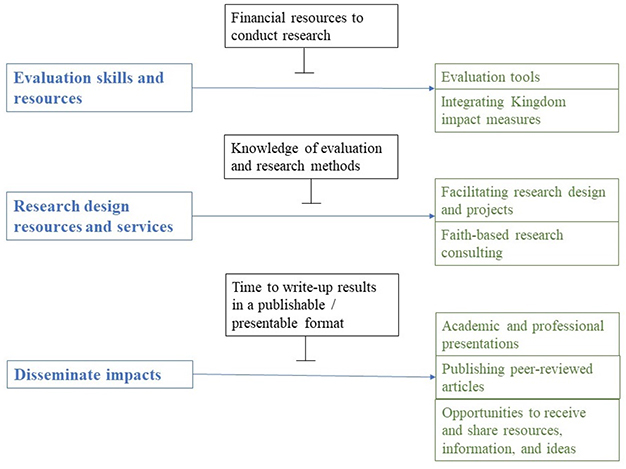

Figure 1. A model of suggested priorities, supporting objectives, and potential barriers based on the thematic analysis.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Jason Paltzera, Keyanna Taylorb

a PhD, MPH, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology, Baylor University, United States of America

b Baylor University, United States of America

Background: Religiosity and spirituality are recognized determinants of health, yet many faith-based organizations do not conduct or publicly disseminate research or evaluation data to inform practice. The purpose of this study was to assess the feasibility of establishing a collaborative to support small to medium-sized, Christian, global health organizations in producing stronger evidence regarding the practice and application of integral mission health models.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was done using a digital, mixed-method (open- and closed-ended questions) survey. The survey was distributed through a convenience sample of Christian global health networks and member organizations representing over 1,000 primarily small to medium sized organizations. Information was collected regarding organizational research and evaluation publication/presentation experience, collaborative interests, evaluation and research barriers, and priorities.

Results: Responses totaled 116 and came from Christian health and development organizations in Africa, Asia, and North America. The survey revealed three organizational research priorities and areas of desired assistance from a collaborative: 1) disseminating impacts, 2) evaluation skills and resources, including integral mission measurement tools, and 3) research design resources and services. Interests varied depending on whether the organization was based inside or outside of the United States.

Discussion: The study aimed to identify priorities and barriers of Christian health organizations around research and outcomes evaluation. The findings suggest that a Christian research collaborative is not only feasible but could serve organizations throughout the world that have a desire to conduct more rigorous evaluation and research studies and disseminate and publish their results yet lack the time, knowledge, or resources to do so. Future studies should explore financial support systems to sustain a collaborative and create a model that could accommodate the different research and evaluation priorities depending on the location of the organization.

Key Words: faith-based, global health, development, evaluation, research

Religious entities have played an important role in the provision of health services and improving health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1,2 Some reports state as high as 70 percent of all services being provided by faith-based organizations (FBOs) in developing countries.3-6 The contributions of FBOs in alleviating the burden of HIV/AIDs is well known. For example, in 2004 the World Health Organization estimated FBOs as comprising 20 percent of all agencies worldwide working towards HIV/AIDs support.7 This is specifically relevant in countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where FBOs provide the most aid, second to governmental providers.8 With nearly 85 percent of the world’s population identifying as religious, it is inherent that FBOs play a critical role in the health and development of communities.9

Faith-based health entities provide financial, human, and technical resources across primary, secondary, and tertiary care levels.4,10 Improved geographic access, increased response systems, and greater trust and influence among community members are often strengths of FBOs in health and development efforts.4,10-13 Faith-based health entities can facilitate resilience within national health systems with the ability to continue service even during periods of political, financial, ideological, and health shifts or crises.4,14-15 FBOs are often the established and trusted organizations that promote values such as connection, forgiveness, agency, blessing, and hope which serve to promote human flourishing.16 Furthermore, religious entities and FBOs have long histories of advocating for justice and against inequality among communities, given their ability to reach the poorest and offer a basis for understanding suffering and justice through spiritual teaching.17-18 However, faith-based organizations face challenges related to evaluating and conducting rigorous research that considers important associations extending beyond basic output measures. Strengthening their research capacity will increase the evidence-based strategies to fight poverty and injustice and improve health through and alongside these entities.19

Strengthening the research and evidence around faith-based approaches will encourage public-private (faith) partnerships. The public sector recognizes the importance of the private community, particularly in the delivery and financing of health services.20 In 2010, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution which encouraged countries to engage with the private sector including faith-based agencies that can provide essential healthcare services to hard-to-reach communities.21 Expanding and deepening such nontraditional partnerships may serve to further community wellbeing.16 The motivation for private and public entities to engage with each other is often supported by the premise of mutual values and objectives regarding quality health care and improving access to and quality of resources.11,22 Alignment of public health and religion through private-public partnerships can be a barrier due to a lack of a common language and goals, existence of evidence-based strengths on both sides, and acknowledgement of ideological differences.17,23-24 Strengthening the research on spiritual determinants and program effectiveness from faith-based health organizations published in credible sources and journals can improve alignment and, therefore, strengthen critical public-private partnerships.24

Effective partnerships with FBOs can also increase their capacity to utilize existing research in order to contribute to the movement of knowledge toward better global health practices to meet the Sustainable Development Goal number 17: “Partnerships for the Goals.” The existing gap in evidence limits the influence of FBOs by not understanding the different mechanisms of how faith-related factors add value to the public-private partnership.10-11,26 This lack of evidence may perpetuate imbalances of research and practice between public/secular and private FBOs.27 In order to adjust the balance, researchers and faith-based community health providers need to find ways to collaborate in the research processes and move toward a common language addressing current and emerging needs.27

The purpose of this study was to identify research and evaluation experience, research and evaluation-related capacities, and obstacles to conducting research and outcome evaluations among small to medium sized Christian global health organizations. The goal was to identify interest areas and objectives of a Christian research collaborative aimed at strengthening the evidence supporting the practice and application of holistic health and integral mission in diverse contexts.

A cross-sectional study was done using an online English-language survey incorporating open- and closed-ended questions to assess the research and evaluation interests, capacities, and barriers of FBOs to conducting more rigorous studies. The survey link was sent via email and social media platforms (Facebook and Twitter) to a convenience sample of Christian health networks and member lists representing more than a thousand organizations and institutions. The survey notification messages, or posts, likely did not reach all of the network organizations, and the authors did not directly communicate with the sample of potential respondents. This is a limitation in understanding the true number of those not responding compared with the network members not receiving the request to complete the survey link. Another likely reason for nonresponses from organizations was the language of the survey, English. Respondents (n=144) represented healthcare and clinic service organizations (22 percent), capacity building organizations (38 percent), churches or houses of worship (12 percent), and higher education (12 percent) from countries in Africa, Asia, and North America. Respondents included some large international FBOs with most representing small- to medium-sized organizations based on organizational reach and revenue sources (private donations versus government grants) determined from organizational websites and prior knowledge of the organizations represented. This study did not analyze organizations based on size and could be a focus of a future study.

Universities and government agencies were excluded (n=28) to focus on community-focused health organizations. It is expected that focusing solely on community-based global health organizations will allow for a more specific exploration of how evaluation and research capacity can be strengthened outside of the academic and government sectors. A follow-up study could focus on potential academic partners to support a collaborative. Survey questions included closed-ended questions concerning experience in publishing in peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations, research and evaluation support, and selected research barriers. Closed-ended questions were analyzed with univariate and bivariate statistics using a significance level of p<0.05. Open-ended questions asked about priorities of a potential collaborative and general research and evaluation interest areas. Open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic inductive qualitative analysis approach.28 An inductive analysis approach was used to allow the themes to emerge from the data.28 All open-ended questions were read and coded by both authors. Disagreements in coded responses were discussed and reconciled to determine the appropriate theme. The analysis was conducted in two stages. First, survey responses were coded by both reviewers. Secondly, codes were categorized into overall themes guiding the interests, capacities, and obstacles of the FBO’s respondents. Table 1 lists the identified themes and codes used to determine the themes. The analysis compared US-based with non-US-based organizations because of the unique funding environment and organizational resources accessible to US organizations. All respondents provided consent prior to initiating the survey and given the option to withdraw from the survey at any point.

The analysis included 116 organizations with 64 (55 percent) based in the United States. Of the total, 30 (25.9 percent) were categorized as healthcare organizations, 17 (14.7 percent) churches or houses of worship, 18 (15.5 percent) mission agencies, and 51 (44.0 percent) capacity building organizations. Table 2 shows the results of organizations with research experience, research and evaluation interest areas, and barriers.

| US-based organizations (N=64) (%) | Non-US-based organizations (N=52) (%) | Total (N=116) (%) | p-value | |

| Current Research Experience | ||||

| Experience publishing in a peer-reviewed journal | 24 (37.5) | 19 (36.5) | 43 (37.1) | 0.965 |

| Experience presenting at an academic conference | 35 (54.7) | 23 (44.2) | 58 (50.0) | 0.534 |

| Rated Interest | ||||

| Disseminate impacts | 51 (79.7) | 44 (84.6) | 95 (81.9) | 0.581 |

| Research and evaluation methods | 54 (84.4) | 41 (78.9) | 95 (81.9) | 0.416 |

| Faith-based research consulting | 46 (71.9) | 37 (71.2) | 83 (71.6) | 0.409 |

| Academic & professional presentations | 40 (62.5) | 35 (67.3) | 75 (64.7) | 0.828 |

| Publishing peer-reviewed articles | 39 (60.9) | 35 (67.3) | 74 (63.8) | 0.554 |

| Barriers | ||||

| Few financial resources to conduct research | 39 (60.9) | 36 (69.2) | 75 (64.7) | 0.353 |

| No time to write-up results in a publishable format | 40 (62.5) | 24 (46.2) | 64 (55.2) | 0.078 |

| Limited knowledge of evaluation and research methods | 27 (42.2) | 32 (61.5) | 59 (50.9) | 0.038* |

| No time to collect data | 37 (57.8) | 20 (38.5) | 57 (49.1) | 0.038* |

| No time to analyze data | 37 (57.8) | 17 (32.7) | 54 (46.6) | 0.007* |

| Measurement is not viewed as a priority | 7 (10.9) | 8 (15.4) | 15 (12.9) | 0.478 |

| Other | 13 (20.3) | 8 (15.4) | 21 (18.1) | 0.439 |

Note. * Significance (p<0.05) determined using Chi-Square test.

More than a third of the organizations (37 percent) had experience publishing in a peer-reviewed journal with no difference between US and non-US-based organizations. Half had experience presenting at a professional or academic conference at the time the survey was conducted (December 2018 – February 2019). Research and evaluation interest areas and barriers were measured using a 5-point Likert scale of Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. Agree and Strongly Agree responses were collapsed as a positive response to each statement. Over 80 percent of organizations expressed interest in 1) gaining a greater capacity to disseminate impacts of their programs and 2) greater understanding of research and evaluation methods. The third ranked interest was faith-based consulting services as an interest area among 72 percent of organizations with little difference based on location. Academic or professional presentations and publishing were highly selected by more than 60 percent of organizations.

The top barriers to research and evaluation were 1) financial resources to conduct research (65 percent) and 2) time to write-up the results (55 percent). Time to write-up results was higher among US-based organizations along with time to collect data and time to analyze the data (58 percent among US-based organizations). Knowledge about research and evaluation methods was the second barrier for non-US organizations (62 percent) and a point of divergence between US and non-US organizations (p=0.038). The differences in time to collect data and analyze results as barriers were statistically significant between US and non-US organizations (p=0.038 and 0.007, respectively).

Table 3 shows the results of the qualitative thematic analysis of service interest areas and expressed objectives of a Christian research collaborative. The service/resource most commonly mentioned by the organizations was evaluation skills and resources (29 percent) followed by research design resources and services (23 percent). This is in line with the focus of the survey. The third most mentioned resource was program development resources. This highlights the potential use of a collaborative to help organizations apply research and evaluation to inform organizational growth. US and non-US-based organizations shared these three most commonly mentioned services/resources. The suggested primary objective of a Christian collaborative mirrors the requested services/ resources of providing evaluation tools (29 percent). The second most mentioned objective of a collaborative pertained to measuring integral mission or Kingdom impact—the impact of integrating spiritual and physical factors in one model or program (22 percent). Among US-based organizations, these two objectives are similarly the first and second most mentioned; however, among non-US-based organizations, the first and second most mentioned objectives of a collaborative pertained to the provision of evaluation tools (26 percent) and the dissemination of information and sharing ideas (26 percent). Only 9 percent of US-based organizations mentioned the objective of disseminating information and sharing ideas, which highlights the differences in objectives among US versus non-US organizations.

Table 4 summarizes the willingness-to-pay for consultation or services regarding research or evaluation projects. A quarter of the organizations (27 percent) were willing to pay up to US $1,000 with another 38 percent willing to pay up to US $500. Only 10 percent stated they would not be willing to pay at all. No significant differences were observed in willingness-to-pay among US and non-US organizations (p = 0.548)

| US-based organizations (N=64) (%) | Non-US-based organizations (N=52) (%) | Total (116) (%) | p-value* | |

| $0 | 8 (12.5) | 4 (7.7) | 12 (10.3) | 0.548 |

| $1-500 | 20 (21.3) | 25 (48.1) | 45 (38.8) | |

| $501-1,000 | 19 (29.7) | 13 (25.0) | 32 (27.6) | |

| $1,001-5,000 | 10 (15.6) | 7 (13.5) | 17 (14.7) | |

| More than $5,000 | 4 (6.3) | 2 (3.9) | 6 (5.2) | |

| Other | 3 (4.7) | 1 (1.9) | 4 (3.5) |

Note. *Significance was determined using Chi-Square test.

The results show a high degree of interest in disseminating impact and understanding research and evaluation methods. US and non-US faith-based organizations want to grow their capacity to measure outcomes (evaluation) and test hypotheses (research) to inform program growth or new areas of service as well as publicly disseminate and share findings. This dissemination could include academic or professional forums to exchange ideas with other similar organizations or in the peer-reviewed literature (64 percent interest). These are complementary and confirm that organizations consider this a high priority even though only a third to a half have prior experience with this type of dissemination. Consulting services in faith-based research and evaluation were of interest to 72 percent of the respondents. Across all the options listed, there was an overall high-level of interest among the responding organizations.

Barriers of financial resources and time to write-up results were expected. This is in line with those organizations that may have some level of monitoring and evaluation already happening but do not have the time or are uncertain what to do with the data that has been collected. Among US-based organizations, the time to collect and analyze the data was also high, suggesting that organizations may not be certain about the measurement design or strategies used to collect the data which lead into the analysis and interpretation. Organizations often collect program output data that may or may not align with the organization’s theory of change or logic model resulting in a disconnect between the data and expected outcomes. Identifying valid and easy-to-use instruments can help address this barrier as well as analytical methods that help establish a comparison group such as propensity score matching. In the area of holistic and faith-based health ministry, there are not many tools that equip organizations with the ability to measure the spiritual determinants of health in relationship to the physical, social, environmental, and economic determinants.30 The ones that do exist require an established evaluation and learning team or additional support to implement the tools with fidelity. These findings suggest that there is a need and a demand for such integral mission or holistic health instruments that can be implemented without much demand on existing staff time or cost.

Among international organizations, there is a need to increase the level of knowledge around research design and methods. A faith-based collaborative focused on serving small to medium sized organizations could be a valuable resource to link organizations and their work to various opportunities for quantifying and disseminating the evidence they are observing in the field.

Twelve percent of organizations mentioned interest in having the collaborative be a facilitator of research projects. A follow-up study could clarify this expressed objective among organizations, which would significantly influence the services provided by a collaborative. This is highlighted by the finding that 15 percent of respondents would be willing to pay between $1,000-$5,000 for evaluation or research services. Most of the respondents were willing to pay US $1,000 or less with more than half of the international organizations willing to pay up to US $500.

Purposes of a qualitative analysis may be to generate a model or hypothesis for subsequent study, to better understand patterns, to explore difficult to quantify topics, or to validate quantitative findings. With this qualitative analysis, a model including priorities, objectives, and barriers was generated for subsequent study and validation. Figure 1 summarizes the top three priorities (blue) and maps corresponding secondary themes (green) that support them based on the open-ended questions.

Figure 1. A model of suggested priorities, supporting objectives, and potential barriers based on the thematic analysis.

Top barriers (black) that need to be addressed in order to create an effective collaborative that provides evaluation and research services desired by faith-based organizations are also shown. A collaborative should emphasize the priority of helping organizations disseminate their own evidence but also create opportunities to learn from other similar organizations working in their region or topic area. This dissemination may help minimize the tension between and increase opportunities to build private-public sector partnerships in global health. Such partnerships may lead to greater financial resources for ongoing measurement and research. The collaborative could help organizations develop their own tools or provide access to a selection of free or low-cost validated health measurement tools, including integrated Kingdom impact measures. This could be accompanied by training and support on how to apply the tools to their specific environmental context and theoretical questions related to key program assumptions. As organizations strengthen their Kingdom-focused evaluation and research capacity, evidence will be available and accessible to create publishable and presentable materials for dissemination and sharing through professional platforms.

Current efforts in forming evidence-generating collaborations among faith-based organizations are limited. One example is an initiative of the Global CHE (Community Health Evangelism) Network called the Public Health as Mission Research Network. The network consists of global health practitioners and researchers focused on discussing, sharing, and designing research studying the integration of faith, public health, and development. The Accord Research Alliance is another example focusing on measuring what matters in the field of Christian relief, development, and advocacy. A third example is the Joint Learning Initiative on Faith and Local Communities (JLI). The JLI has worked collaboratively with local, national, and global faith groups to develop The Guide to Excellence in Evidence for Faith Groups.30 According to JLI, gathering and collecting evidence helps organizations track how their work impacts the communities they serve in alleviating poverty and improving overall well-being. Christian health organizations regardless of size or location may benefit from a collaborative that aligns with and addresses the priorities and barriers identified here.

This study has several limitations, including possible selection bias based on a convenient sample of organizations that were part of the networks used to distribute the survey link. Since the survey was digital and in English, it excluded many organizations that do not have consistent access to the internet or are not comfortable responding in English. This study is also limited by a low response rate which may introduce additional self-selection bias. While over 1,000 organizations were likely exposed to the survey link through network newsletters, email messages, and social media posts to participate in the survey, only 116 organizations provided complete responses. The total number of individuals representing organizations that may have received the survey link and chose not to complete it or who simply failed to open the message containing the invitation is unknown. This low response rate may reflect organizational challenges or the low priority for the evaluation of practices and/or to disseminate research among FBOs. The purpose of this study was to explore topics and themes around a Christian collaborative to support faith-based global health organizations in their capacity to design, collect, analyze, write, and disseminate evidence of their work. The study is limited in its ability to make associations between organization types and existing capacities.

A strength of the study is broad scope and geography of organizations exposed to the survey given the reach of member networks used to distribute the survey. The relatively large sample size allowed the analysis to be stratified by US and non-US organizations resulting in a greater understanding of perceptions and needs around capacities to conduct community-based health research.

The findings show the need for and interest in a faith-based research and evaluation collaborative or system. There are some differences in interests and barriers between US and non-US-based organizations that should be considered to focus efforts according to the perceived need and available resources. The study identified three priority areas among Christian health organizations focusing on 1) assistance in disseminating results of program impacts, 2) strengthening evaluation skills and tools, including integral or holistic mission measurement tools, and 3) guidance in identifying research design resources and services. Future research should test the feasibility of a faith-based collaborative to further clarify a process for meeting the objectives identified in this exploratory study.