Figure 1. Length in time in months from community identification for CHE and first CHE home visit

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Jason Paltzer a, Keyanna Taylor b, Janak Patel c

a MPH, PhD, Visiting Professor, Wisconsin Lutheran College and founder/director of the Center for Community Health Ministry, USA

b BS, MPH, PhD student at University of California, Los Angeles, USA

Background: Integral mission health models are often employed by faith-based organizations to address social, physical, and spiritual wellbeing. Given the use of these models like Community Health Evangelism (CHE), the evidence regarding their effectiveness in practice is limited. The purpose of this descriptive study was to identify variation in the initiation, development, implementation, and impacts of Community Health Evangelism as reported by organization members of the Global CHE Network.

Methods: A digital survey in English, Spanish, and French was sent via email to Global CHE network members resulting in 27 complete organizational responses for analysis. Survey questions ranged from qualitative open-ended questions to categorial and ranking type questions. Descriptive statistics and inductive thematic analytical methods were used to describe the data. Data were summarized according to organizational size to better understand this influence on the practice of CHE. Responses represent organizations in Africa, Asia, North/Central America, and Europe.

Results: The community selection process, committee and CHE volunteer selection criteria, the function of the community champion, time to CHE volunteer home visitation, and achievement of key impacts were some of the areas that showed variation. Measured impacts included understanding of integral mission, use of LePSA(S) as a teaching strategy, multiplication, and community ownership.

Discussion: The study aimed to understand the implementation of CHE in the field and identify areas of variation and adaptation that could lead to opportunities or barriers in achieving the desired impacts of CHE. The results show variation in each of the four phases and provide a starting point to further study CHE as an integral mission model. The paper suggests additional opportunities for future research to identify core components that could strengthen and improve the effectiveness and practice of integral mission models.

Key words: integral mission, community health evangelism, implementation research

Community Health Evangelism (CHE) is the practice of creating transformational outcomes and impact in communities to improve their overall health and well-being. Transformation is based on understanding the community’s worldview, beliefs, and values as the foundation for creating sustained behavior change on the family level while addressing broken systems and infrastructure on the community level. CHE combines a Christian worldview and values with local ownership and engagement to create a model of wholistic developmental work. The Global CHE Network is an association of people and faith-based organizations (FBOs) that use CHE to serve impoverished communities in primarily rural settings around the world. It represents over 975 members including at least 70 organizational members in over 138 countries.1

CHE was developed in 1979 by Stan Rowland and tested over the next decade as a program of Campus Crusade in Uganda and Kenya. The motivation to grow community health was influenced by the Declaration of Alma Ata from the World Health Organization in 1978 and the work of medical missionary and global health pioneer, Carl E. Taylor. The Declaration of Alma Ata promoted Health for All and expanded the definition of health, health care, and wellbeing. The Community Health Worker model grew from this declaration and extended the practice of health into the hands of people in the community as agents of change and decision makers for health. CHE builds on this initiative by integrating community engagement with biblical values through participatory lessons that help families reframe their beliefs according to biblical values. CHE uses a training of trainers (TOT) approach that facilitates multiplication and shifts the focus of the program from the supporting organization to the community. Three trainings complete the program—ToT 1 (CHE foundation and process), ToT 2 (roles of the committee and training CHEs), and ToT 3 (measuring and multiplication). See https://chenetwork.org/about-che-training/ for more information about the training structure.

Research shows that FBOs are successful at supporting development efforts in underrepresented or marginalized communities.2-4 Many FBOs are holistic in that they implement diverse strategies to address the multiple dimensions of poverty including health, education, and livelihood. For example, church-based interventions have been proven successful in targeting minority communities for hypertension/weight management programs in the United States.5 FBOs have been used in all stages of program implementation such as needs assessment/asset mapping, program planning, and evaluation.2-3, 6-7

Multiple factors affect the success rate of FBOs’ implementation of interventions. The size of the religious organizations, varying financial capabilities, the extent of partnerships in the community, ability of volunteers to help with the program, and spheres of influence have been noted in literature.12-14 In addition, religious leaders can have a significant impact on the success of the program or intervention. These leaders are often trusted gatekeepers in the community and are well respected. Their attitudes and beliefs are important factors that can affect an acceptance and adoption of a health intervention.15-17 The available community assets and resources are often different as well as the motivation to organize those assets for the good of the group. This can influence the time for implementation, program sustainability, and long-term community ownership depending on how the FBO responds to such differences. Furthermore, the political and social climate in the region can affect a program’s effectiveness.17-19 For example, the existing stigma around anti-retroviral use in sub-Saharan Africa often presents a challenge in health promotion efforts or interventions.10 Lastly, the diversity and unique experiences of community members can affect a program’s effectiveness. For example, a person’s socio-economic status or cultural identities can affect access to healthcare or violation of human rights.

CHE organizations interface with many of these influences and systems. For this reason, it is important to examine the implementation of CHE programs by FBOs to increase their chances of transformational impact in serving communities with differing characteristics and cultures. The purpose of this descriptive cross-sectional study was to identify common core competencies, implementation steps, and field-based adaptations of the CHE model to provide insight for future CHE communities. A second objective was to identify self-reported achievement of the CHE values. While there has been extensive research conducted on church-based, health programs, there are significant gaps in the literature regarding interventions that use integral mission health models such as CHE. One gap in the literature is a comparison of CHE programs across countries. This could impact future development of faith-based, public health interventions given the cultural beliefs and geopolitical characteristics that influence community selection, entry, training, and implementation.

FBOs will continue to serve a vital role in development as well as disaster management as observed during the COVID-19 pandemic.18 CHE is one model that could serve as a critical strategy for organizations looking to strengthen the local Christian church in carrying out her mission to share the centrality of Jesus’ love for whole-person health leading to community transformation. Given the potential for FBOs to successfully implement programs using the CHE model, this descriptive study describes the some of the variation in implementation along with achievements of CHE in the field and discusses opportunities to strengthen the model to achieve the CHE values. This study was done in collaboration with the Global CHE Network. Ethics review was not obtained given the survey focused on program characteristics and did not include individual or personal information.

The purpose of the qualitative descriptive study was to evaluate Global CHE Network organizations’ implementation of CHE within model communities. An online survey was developed to assess implementation of CHE using a variety of closed and open-ended questions. The survey included a total of 23 items and assessed aspects of CHE programs including: 1) Program Initiation; 2) Program Development; 3) Program Implementation; and 4) Program Impact. The population surveyed were member organizations of the Global CHE Network. The survey was developed using the Qualtrics software and a link to the survey was sent via email and by means of the Global CHE Network newsletter. The survey was available in English, Spanish, and French.

The survey was launched 8/18/2020 and closed 11/8/2020. A follow-up survey was sent on 1/17/2021 to gather clarifying information regarding three questions about CHE home visits initially assessed in the survey. The follow-up survey was closed on 2/18/2021. Eighty-two responses were collected through the Qualtrics survey link, and two additional responses were submitted via Word document or PDF and entered into Qualtrics. Of the total 84 responses, 27 blank surveys were removed. Responses were considered blank if there was no associated respondent name or organization name provided as it was not possible to confirm the validity of the response coming from an implementing CHE organization rather than an individual “informational” member. Fifty-seven responses were considered for further analysis. Of the 57 respondents, responses were considered invalid if more than 50% of the questions were left unanswered. This left a total of 27 valid responses for the analysis.

The survey assessed CHE program initiation, development, implementation, and impact. Program initiation evaluated the steps used to identify the community, community characteristics that were used to select the community for CHE implementation, and how trainers entered the community. CHE program development was evaluated by assessing the CHE approach utilized, how CHEs and committee members were identified and selected; strategies utilized to strengthen relationships between CHEs, committees, members, and trainers; the role of the community champion; and the length of time between community selection and the first CHE home visit. Program implementation was evaluated by assessing the number of households being visited by CHEs, the frequency of home visits, the number and type of additional community activities implemented by CHEs, and the primary area of projects the CHE program has supported. Lastly, program impact was evaluated by assessing achievement of six CHE values. This included assessing whether programs integrated physical and spiritual wellbeing, program multiplication, community ownership, the use of the LePSA(S) (Learner-centered, Problem-solving, Self-discovery, Action-oriented, Spiritual) learning methodology, the holistic prevention of disease, and the use of local resources. The survey is available upon request from the authors.

The organizations were categorized as “small” or “large” based on the number of active CHE communities. This was done to help evaluate potential differences between organizations with larger support teams, experience, and resources given the influence these might have on the ability and capacity of the organization to support the CHE process. The distribution of the organizations based on number of CHE communities created a clear bimodal distribution with five communities as the dividing point. This distinction was by no means a perfect indicator of “size” but was helpful as a strategy to analyze the data for the purpose of the study.

Responses in Spanish were translated to English by a member of the research team and French responses were translated to English using an online translation software (www.deepl.com/fr/translator). Open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic coding and analysis. An inductive approach was utilized to examine how Global CHE Network organizations implement CHE. Codes were developed from a preliminary review of survey responses by the team of researchers and each response was subsequently coded independently by two researchers. Codes were consolidated and were then categorized into themes by the research team collaboratively (Table 1). Closed-ended quantitative questions were analyzed by calculating frequencies. Microsoft Excel was used for managing and analyzing the survey data.

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the respondents with the majority coming from Africa followed by Asia. Where the analysis stratifies by the size of the organization, the number of CHE communities supported by the organization was used for the categorization, with those serving more than five categorized as “large.” The strategy has limitations but valuable to obtain potential differences based on the number of communities served. Water and sanitation, education, and agriculture were the primary service areas among the respondents.

Table 3 describes the self-reported steps (open-ended question) used by the organizations to identify a community. A general information gathering and assessment approach was the primary method for identifying a community. In other situations, a community champion, church-based referrals, an informal relationship, or program feasibility (proximity, ease of access, etc.) was used to identify the community. An asset-based approach is highlighted in that most organizations selected the community because of the physical, material, or human capacity (assets) available in the community. In some situations, the vulnerability and acceptance of external support determined the selection of the community. The results show a multi-step approach to selecting a community the number of strategies organizations use to select a community.

Table 4 shows the variation in the suggested steps described in the CHE ToT 1 training. Building relationships through informal interactions is the first step for most CHE organizations. Step 2 is generally a formal community needs assessment or survey followed by community awareness raising whether through a school screening or other awareness strategy. The identification of a community champion was scattered throughout the process with the champion identified as steps 1, 2, or 3. In general, small organizations relied on identifying a community champion as the first step whereas larger organizations first engaged in informal interactions before identifying the community champion. This suggests that small organizations might depend on a specific individual from the very beginning whereas larger organizations may engage in more informal connections and community meetings before identifying and engaging a local community champion.

Table 5 describes the general CHE approach used, the process to select the committee and community health evangelists, and the focus of the community champion during development and maintenance of the program. The primary approach used was the community-based approach followed by the church-based approach. The other CHE approaches were used but not very common. Selecting the committee members was done using three main strategies—community consensus, selection by community leaders, and individual characteristics as observed by the training team. The community leaders may have used individual characteristics as part of the selection process but was not specifically stated in the data. Larger organizations tended to use existing community leadership to select committee members more often than smaller organizations. When it came to selecting the community health evangelists, the dominant approach was selection through leadership of the established committee. This is in line with the model suggested by the CHE training. Individual characteristics were used likely in combination with the leadership model. In some cases, church leadership or community consensus was used to select the CHE volunteers. The majority of organizations used formal strategies to strengthen the relationship between the committee and the CHE’s. Formal strategies include organized meetings, service projects, and joint education opportunities. The role of the community champion often changed from serving as a mentor or manager/organizer during the development of the program to either dropping off completely or focused on an active management role during the maintenance of the program. This transition could be a critical factor in the success of a CHE community.

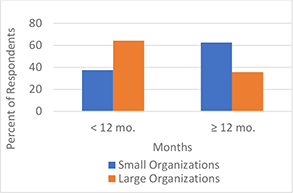

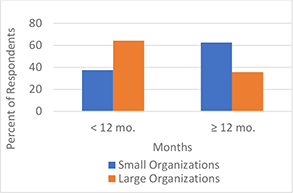

Figure 1 shows a difference in the time between community selection and a community health evangelist visiting homes. Small organizations tend to take longer (greater than 12 months) in developing and organizing the committee before a home is visited whereas larger organizations do this in less than 12 months. The difference in this timeframe could be another factor in overall achievement of transformation outcomes leading to multiplication or related to efficiency factors of organizations working in more communities.

Figure 1. Length in time in months from community identification for CHE and first CHE home visit

Table 5 describes the implementation of the CHE program. Most organizations have CHE’s visiting households on a regular basis with many of them individually visiting less than 25 families at any given time. CHE’s typically conduct visits on a weekly basis. CHE’s also organize community-level events around common topics of general health and disease and CHE program activities including supporting the committee, community surveys/assessments, prayer sessions, and training of other CHEs. Nutrition and child/youth education activities were also common more so among larger organizations.

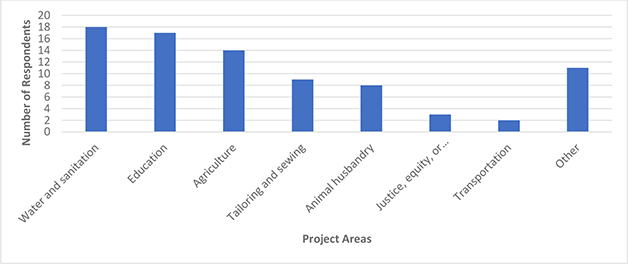

Figure 2 shows the distribution of common seed development projects implemented by the CHE Committees and evangelists. Water and sanitation, child education, and agriculture were the top three project areas. Justice, equity, and advocacy projects appear to be a growing area for CHE communities.

Figure 2. Primary area of projects supported by CHE programs

Table 5 describes the extent to which organizations believe they are impacting communities based on four values of CHE, understanding of holistic health or integral mission, local ownership or control, use of the LePSA(S) methodology, and use of local resources or asset-based community development. Understanding of holistic health or integral mission is an area to explore given that more than half of large CHE organization communities have an incomplete understanding of integral mission and, therefore, the connection of spiritual faith to their health and well-being. The results suggest that smaller organizations might achieve a greater level of understanding of this value. Few CHE communities seem to have a perceived level of complete control of their development. A limitation of this value is the understanding how “complete control” is defined as a standard definition was not provided in the survey. The most common response was that communities have a “moderate” amount of control and is an area to consider for improving CHE strategies. Local resources were primarily assets of physical space and materials following by people’s time. Many CHE communities were not providing monetary support to the activities or in support of the program. This confirms the need to be flexible on what projects are determined based on the resources often available in rural areas.

Multiplication is another CHE value. The mean number of additional communities adopted CHE from the hub community was approximately 3.4 additional communities. The range was large with two communities having multiplied to more than 20 communities each. This diverse capacity for multiplication is likely dependent on the geographical context, population density of the area, and intended use of CHE by the organization. This is an important aspect given the intention of CHE is to be a model that is easily multiplied to neighboring communities.

This study describes the initiation, development, implementation, and impact of CHE communities. The objective was to identify specific processes that lead to strategies, competencies, or components to increase the effectiveness and sustainability of CHE in lower-income rural communities. Based on the results, organizations and communities show variation in key areas relating to committee and CHE selection, the role of the community champion, community-level activities, seed development projects, and time from introduction to CHE visitations.

Community selection is the first component of building a CHE program. A variety of methods were stated as activities in selecting a community. The most common included some form of information gathering, reliance on a community champion, other informal relationships, or a church-based referral/request. Other times, the team would identify communities based on specific human, material, or physical capacity or expressed acceptance of a Christian health program. When respondents were asked to list the order of steps, considerable variation was observed between steps two through five. The placement of conducting an assessment, building community awareness, and selecting a community champion or person of peace varied. This is one area for further study as this order may determine overall community involvement and ownership over time as an important impact. The values expressed during this initiation period are also important including expectations of external resource contribution for seed projects, the purpose of the model, and multiplication strategy. The CHE trainers can strengthen the importance of following the five steps in the order they are taught to ensure strong understanding of the program leading to effective selection of the committee and CHEs to lead the program.

One realization when initiating a CHE program is the difference in how committees and CHEs are selected. Committees are primarily selected by community consensus while CHEs are selected by the church or committee in line with the recommended CHE approach. This approach could be discussed on the community level to integrate a participatory element into selecting the CHE’s as well. Assuming committees have the trust of the community to make this selection, the current process would be more efficient. The selection of the committee and the CHE’s are significant steps in the overall success of the CHE model. When individual characteristics were selected as the identification method, the data did not provide who was involved in determining these characteristics and an area for future research.

The relationship between the committee, CHE volunteers, and the community is also important. Given the reliance on local relationships within the CHE model, strengthening these relationships can be done through formal and informal strategies. Such strategies included Bible studies, formal meetings, community or neighbor-to-neighbor service projects, and professional development trainings. Organizational characteristics of the training team could be important to help explain if some organizational types tend to rely more on formal, informal, community, or church-based relationship building strategies. The role of the local church within a CHE program was not a specific focus on this survey but integration within a local church may be a key indicator of a successful CHE program. It is uncertain as to the extent of this integration when a community-based approach is used. The most common approach type followed was the community-based approach followed by a church-initiated approach. The community-based approach starts with a school screening to build awareness and identify local leaders from the community to set up the initial committee. Once families are visited by CHEs, the expected outcome is that growth groups form among multiple families which then come together to form a church. The expected time from community selection to CHE’s visiting families is typically 12-18 months. The results show some difference in this timeframe based on the size of the organization.

The role of the community champion appears to transition during the life of the CHE program in each community. It is important for the organization or training team to recognize this and support the champion during this transition. In the beginning, the champion is instrumental in relationship building, recruiting CHEs, planning awareness events or trainings, liaising between partners, and providing initial financial/in-kind support. As the program gets going, the champion shifts to an advocacy, spiritual mentoring, and/or supervisory role or involved with multiplication. In addition, communities and organizations might define “community champion” and “person of peace” differently as both individuals are discussed in the CHE training. This also might account for the difference in the management versus mentorship roles described in the data.

Implementation of a CHE program involves CHE volunteers modeling health behaviors, visiting homes, conducting health lessons, and organizing community events or projects along with the committee. Most respondents stated that CHE volunteers were visiting homes on a regular basis while a few were uncertain. The recommended number of homes for one CHE volunteer to serve at a time is between 10-15 and is the range for most respondents. A few are visiting many more than this and suggests a different structure where the CHE volunteers might be given a compensation and working more hours per week compared to a volunteer CHE. This high visitation load could also explain why some programs are not seeing a better understanding of integral mission and community control/ownership as the lessons might be cut short for time. The survey also asked about additional responsibilities of CHE volunteers, which included disease management, program evaluations, committee meetings, organizing food and nutrition programs, youth education events, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programs.

CHE Committees also organize community-level development projects or seed projects. These projects targeted WASH, nutrition/agriculture, tailoring, and animal husbandry. Other initiatives focused on social justice and transportation issues. Stronger guidance around community-level or service-oriented projects might be beneficial for committees as they work to support the family-level changes to create community transformation. It is uncertain if the community-level projects are determined by the organization, the committee, the CHE volunteers, the community, or a combination of these groups.

The length of time between community identification and CHE volunteers visiting homes varied based on the existing number of communities being served by the organization. As the organization increases in scope with more communities, the timeline shortens. The survey did not get into reasons for this, but some initial thoughts could be related to learning the process and developing an efficient pathway to complete each step in a shorter time. Another aspect could be related to the balance in developing relationships upfront as the organization establishes a presence in the region. Once trust is built in a couple of areas, it might be easier for that organization to build strong relationships based on past presence and exposure in the region. As mentioned earlier, the definition used to determine “size” was not ideal but does suggest that this is one characteristic to consider that influence the impact of CHE.

The CHE values provide a framework to measure the impact of CHE programs. Based on organizational understanding of the values, the results show good progression toward achieving the values of CHE in addition to areas for improvement.

Participatory learning: The use of LePSA(s) as the learning strategy is well received and applied. It is important to provide organizations an objective way to assess the use of participatory strategies among CHEs educating families in the home.

Integral mission: The understanding of integral mission or wholistic health was high among 11 of the respondents, however 15 of the respondents expressed this understanding as somewhat or a little. The understanding of integral mission is an important feature of CHE. The actual teaching of biblical lessons within the health lesson is an assumption based on the training but might need to be followed up and measured as an area to maintain fidelity to the CHE model. Modeling faith in the homes of CHE volunteers and connection to a local church may also be considerations to increase the movement of organizations into a higher level of understanding integral mission. Another aspect of this could be the perspective of the CHE organizer, trainer, and leader in how integral mission is taught, modeled, and emphasized throughout the process. For example, is there difference if a physician or a pastor is leading the initiative?

Local assets: The use of local assets is a foundational strategy for asset-based community development. The survey asked what types of assets are commonly used to support CHE programs and development projects. The use of space and buildings was the most common mentioned asset leveraged in a community followed by in-kind material contributions. In-kind contributions include building materials, tools, land, vegetable seeds, food, some technology, and other natural resources. A few CHE programs have seen direct financial contributions for micro-enterprise groups, local churches and businesses, government support for projects, and individual contributions to purchase food for events. It is expected that the level of local assets leveraged links directly to the perceived level of community control and requires further study to assess this relationship.

Community control: Three organizations reported that communities have complete control over the program with another ten having a lot of control, which is in line with a partnership model for program management. More than half of the respondents’ stated that communities have a moderate or little to no control over the program. The movement toward community ownership and control is an important feature of participatory holistic development and another opportunity for further research. One limitation of this question could be the understanding of “control” and “ownership” across cultures and regions. A collective culture may understand this concept differently than a more individualistic culture. The intent of this value is to help communities feel a sense of empowerment and dignity in the work, growth, and benefits of the program.

Lastly, multiplication was measured as 3.4 additional communities from the hub or “model” community. The intent of multiplication is that communities are transformed to the point that other surrounding communities take notice and desire to receive the same type of training. One pathway for multiplication is for the local committees and CHE volunteers to share their knowledge and structure allowing other communities to adopt CHE as a development program. Other approaches that are likely used to add communities involves the original training team equipping other communities nearby the model community. The questions around multiplication involve knowing how the daughter communities observed the model communities, who initially shared the knowledge about CHE to the daughter communities, who requested training from the daughter communities, and who provides the training and organizational support for daughter communities. This could be done by the model community leaders or the initial training team and still be considered multiplication.

As noted in the discussion, areas for future study include better understanding of the combination of characteristics used to select the community, initial inputs provided, structure and guidelines for seed projects, and the use of local resources throughout the program that most effectively lead to community ownership. A better understanding of why the initiation process is often not completed in the suggested order also deserves more study given the focus of CHE to take a participatory, asset-based approach to community health and development. Understanding the integration of faith, the Bible, and health requires competency and confidence among CHE volunteers to teach the lessons as developed so the biblical teachings are shared through participatory methods. Following up with CHE volunteers regarding their comfort level and reporting back spiritual conversations with families could help in understanding the effectiveness of this method for integral mission.

Additional questions for future research include:

This study was a descriptive study of CHE organizations. The database included informational members as well as organizational members resulting in a smaller sample size than expected. The current Global CHE Network is limited in its capacity to ascertain organizational members and is currently updating the website and directory to better classify members in the network. As of December 2021, the number of registered organizations is closer to 70. Given the number of organizational members and the response rate, the study was limited to a descriptive study to generate hypotheses.

The qualitative nature of some of the questions allowed us to describe components of the CHE programs as implemented and identify hypotheses for future studies. The survey was offered in Spanish and French allowing for inclusion of diverse CHE programs in different regions of the world.

Community Health Evangelism has great potential to be a faith-based holistic health model for community transformation and poverty alleviation. It is currently being used throughout the world in different cultures and environments. Understanding the model is important to strengthen the foundation for subsequent iterations and adaptations in the field. As CHE is multiplied, there are opportunities for other strategies to work themselves into the model, thus, changing the overall intent of having a model promoting integral mission. Such research is important to help maintain fidelity to the core elements of CHE that make it an effective holistic and transformational approach to evangelism.