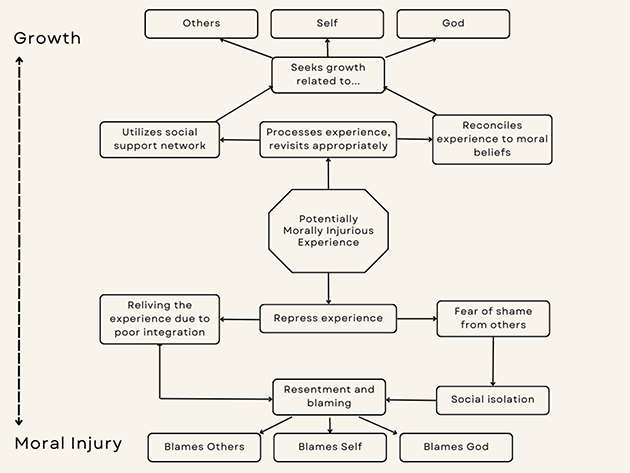

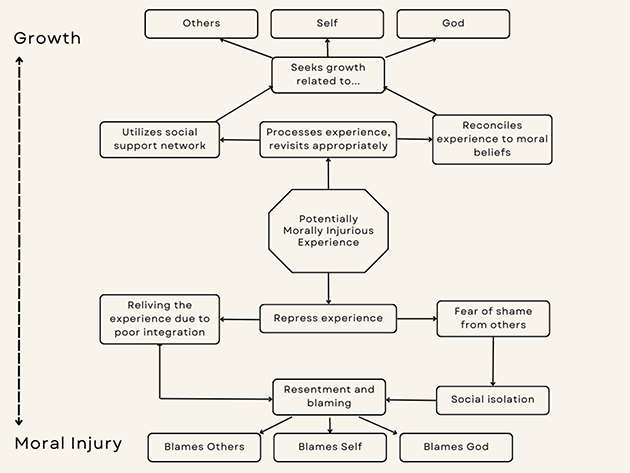

Figure 1: Potentially moral injurious experience pathway to growth or blame

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Jason Paltzera, James Ritchieb, Doug Lindbergc, Michael Topped, Andrew Theisze, Taylor Van Brocklinf

a MPH, PhD, Founder/director, The Meros Center and visiting professor, Wisconsin Lutheran College, USA

b MD, Longevity Project, MedSend, USA

c MD, Director, Center for Advancing Healthcare Missions, Christian Medical and Dental Associations, USA

d DMSC, PA, Associate Professor, Physician Assistant Studies, Marquette University, USA

e MSW(c), Concordia University, USA

f Student Enrolment Counsellor, Concordia University, USA

Moral injury among healthcare missionaries leads to negative consequences for the individual, healthcare team, patients, and sending agencies. Conflicting values in clinical care, culture, and spirituality provide unique potentially morally injurious experiences. The purpose of this qualitative study is to explore the phenomenon of moral injury among western healthcare missionaries to develop effective support and treatment strategies.

A qualitative interview guide was developed based on the existing literature on moral injury. Twenty-one key informant interviews were completed by two former healthcare missionaries. Participants were based in Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe healthcare mission settings. Questions were based on clinical, cultural, and spiritual domains of potential ethical and moral conflicts. Protective factors were also explored based on one’s faith and spiritual practices. Interviews were transcribed and coded independently by two analysts. The team reviewed the codes and determined themes from across the three domains.

Seven themes emerged from the interviews ranging from morally injurious experiences with cultural leadership practices and unfamiliar clinical care experiences to guilt over practicing outside of one’s scope of practice and addressing suffering alongside God’s sovereignty. The themes led to the development of an injury/growth pathway as a potential model for helping healthcare missionaries describe and move through potentially morally injurious experiences.

The themes allow for healthcare missionary sending agencies to develop strategies, training, and support systems for teams preparing to enter the mission field and for individuals already in the field. Recommendations for growing through potentially morally injurious experiences are suggested to guide practice and support for missionaries in the field. The growth values and strategies could inform the development of a screening tool to assess moral injury among healthcare missionaries.

Key words: moral injury, healthcare missions, spiritual determinants, burnout, missionary retention, medical missionary support, resilience

Moral injury (MI) may be experienced after, “perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”1 MI is, therefore, closely related to guilt and shame. MI also is commonly associated with betrayal, in which either the person betrays someone else and feels guilty or the person is betrayed by a trusted person or entity. MI disrupts a person’s concept of moral dependability. The morally injured person may wonder, “Can I trust myself?” or “Can I trust other people?” or “Is God as dependable as I thought He was?” Significant moral injury can lead to social alienation, anger, spiritual crises, and increased suicidality.2

Moral injury literature often references post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as an associated yet distinct phenomenon.3 PTSD typically follows a powerfully emotional event involving fear, such as a threat to someone’s life. MI carries less of an emotional component and more of a spiritual component, with typical symptoms including guilt, shame, anger, anhedonia, social alienation, and a sense of distance from God.4,5 Unlike MI, PTSD is distinctly defined within the DSM-5 and although there are similarities in MI expression, “there is a unique morally injurious phenomenology not accounted for by PTSD.”6 Several effective treatment modalities such as medications and psychotherapy have been identified for PTSD, but clear evidence for effective treatment of MI remains elusive. “Little is known about risk and protective factors that moderate the association between exposure to PMIEs and enduring mental and behavioral health outcomes.”5

Moral injury is a leading cause of significant distress among cross-cultural workers (Davis, B., Schaefer, F., Schaefer, C., personal communication). The cause of this distress is understandable — different cultures have different deeply held values pertaining to vital issues, such as the value of human life and how important decisions are made. When a person from one culture acts consistently with his own culture, he may violate the values of a person from a different culture. For instance, an American nurse, who highly values human life, maybe morally injured if her national colleagues commit infanticide on a twin because they believe that the second twin is a demon.

Moral injury has psychological, intrapersonal, social, biological, and religious/spiritual dimensions.3,5 Religious and spiritual struggles which are commonly reported by morally injured people include “feeling abandoned by God, doubting one’s beliefs, questioning one’s purpose, and perceiving one’s actions to be a violation of a religious/spiritual ethic.” People who identified themselves as more religious have been shown to have an intriguing bipolar reaction to moral injury. Religious people seem to be either relatively protected from MI, or especially susceptible to MI.5

Few studies have specifically evaluated the struggles that health care missionaries (HCMs) encounter on the mission field.7-12 Though these studies have included consideration of issues that relate to MI, none of them have specifically addressed MI or the means to prevent or treat it. This qualitative study was undertaken to explore the phenomenon of MI in HCMs. While some HCMs are deeply affected by MI, other HCMs thrive in the field for decades. The purpose of this qualitative exploratory study was to better understand the experience of MI among HCMs so that subsequent studies may confirm and lead to evidence-based recommendations for the prevention and management of MI.

The study was conducted in collaboration with MedSend and Christian Medical & Dental Association (CMDA) in the United States. The study received ethics approval from the Baylor University Institutional Review Board (reference #176044). Participants were recruited from the MedSend and CMDA databases. The team recruited individuals from different regions, specialty areas, and time in the field. See Table 1 for descriptive characteristics of the sample (N=21). Participants were required to be active in the field serving in a healthcare facility or recently returned from serving in an international mission healthcare facility (within 12 months) to be eligible for the study. Participants were recruited and interviewed between July and December 2021. The planned number of interviews was set at 30 but due to time constraints and the quality of the recorded data, 21 interviews were completed. Between 20-30 interviews is suggested as a target range for qualitative studies.13

Participants received a personal invitation via email to participate in the study. When a participant accepted the invitation, they were sent the interview guide to give them an opportunity to prepare for the interview. This was done to avoid any unexpected emotional triggers resulting from the questions and expedite the interview process. Participants who agreed to take part in the study were scheduled for a Zoom interview with one of two veteran healthcare missionaries. Verbal informed consent was obtained to conduct and record the interview for analysis prior to the start of the interview. The interview began with brief introductions and an overview of the intent of the study.

The structured interview consisted of 26 questions (Appendix A) with each interview lasting 90-120 minutes. Probing questions were used to draw out the subjects when further exploration or elaboration about a given topic was warranted.

Themes were identified using an inductive qualitative analysis approach.14 The Zoom auto-transcription function was utilized for each of the twenty-one interviews. Each interview transcript was cleaned for accurate transcription and grammatical errors by one of two research assistants by comparing the audio file to the transcript. Coding schemes for common responses were created for each question and the transcripts were reviewed by two research assistants. The two complete sets of coded transcripts were then synthesized and compared. Significant inconsistencies between codes were reconciled through discussion on coding inclusion and re-examining the “disputed” analysis of the interview transcripts. The study team collectively reviewed the final set of codes allowing for critique and alignment with the interviewers. Major themes were synthesized from the codes based on the number of mentions and important gaps or inconsistencies among the codes. Emergent themes from less commonly mentioned codes were also captured. Other questions either prompted a “yes” or “no” response or were identified on a frequency Likert scale.

Twenty-one HCMs participated in extended key informant interviews focused on understanding their experience with moral injury. Table 1 provides the descriptive characteristics of the study participants. Most were from the United States, one from the United Kingdom, and one from Germany. The mean number of years in the field was 10.8 years with a mean of three tours. Family medicine was the primary specialty area represented among the sample consisting of 19 physicians, one respiratory therapist, and one nurse. Participants reported a weekly mean of 42.8 hours of clinical work and 10.2 hours of administrative work.

Six major themes were extrapolated from the interviews that contributed to identifying the experience of moral injury in the context of the healthcare missionary. The research team searched for situations and experiences where a healthcare missionary felt trapped or bound by competing values between their personal values, host culture values, expectations from other colleagues, or sending organization policies. These would create “double binding” situations that force the healthcare missionary to act in a way that conflicts with his/her own values or the values of the people around them.

Theme 1: Deep sense of personal responsibility for patients conflicts with unfamiliar medical conditions, unexpected requirements, and inadequate resources to carry out that responsibility.

Healthcare missionaries can face a binding situation when they try to carry out their assumed responsibilities and expectations of care in a setting where the local expectations are different and they lack the resources or support to carry out their desired level of care. This may result in anger, frustration, and hurt with local providers, leaders, and health care administrators in the facility.

Example codes: Patient overload, different conditions and expectations of care, different work ethic and investment, exhaustion, no advocacy, not knowing what defines an ethical conflict.

Theme 2: One’s own cultural values of leadership conflict with the cultural values of leadership in the host community.

Leadership practices of the host culture, such as a highly hierarchical structure, may cause conflict with the expectations of a missionary who is accustomed to a more egalitarian structure. It is common to assume one’s home culture is superior to the host culture resulting in a type of cultural bias and imbalance. Yet, these same missionaries are often placed in positions of leadership soon after arrival in the field by nature of their training and role. This can result in frequent recognized and unrecognized conflicts with fellow missionaries or local providers and staff.

Example codes: Professional fulfillment, teaching opportunities, cross-cultural study, frustration with cultural differences, mentorship meetings, job versus service versus vocation.

Theme 3: One’s need to appear professionally competent (vocation) conflicts with feelings of personal inadequacy and incompetence.

Healthcare missionaries may be unfamiliar with local disease entities, health-related beliefs of the host culture, ethical priorities of the host culture, and different administrative practices, leading to mistakes, misunderstanding, and conflict. This results in feelings of inadequacy and incompetence, which may lead to an HCM to question their sense of calling.

Example codes: Spiritual fulfillment, error judgment, giving up, vocation/calling, guilt over care provided, lack of knowledge.

Theme 4: The professional value to practice within one’s training and competence conflicts with others’ desire for the HCM to practice beyond those limitations.

HCM’s desire to abide by their professional scope of practice and training. Yet, they may find themselves in a position, often exacerbated by local expectations and precedent from prior staff, where services beyond their scope of training are expected. Not providing this care may cause harm to patients, as they may not be able to access the care they may need to expend additional resources to access it. Providing care beyond that which one is trained may cause harm as well.

Example codes: Unethical decisions, guilt pressure, different levels of oversight and control, guilt over care provided, high impact cases.

Theme 5: The desire to share a message of God’s love conflicts with an enormous demand for clinical services and extent of patients’ suffering.

HCMs desire to share God’s love with patients, which is a central motivation for entering the healthcare missionary role. This desire can be subsumed by the trauma of frequent and overwhelming suffering among patients whose care demands most of the missionary’s time. This problem is exacerbated by difficulty in communicating spiritual messages in cultures with divergent and traditional spiritual overtones. Without a proper understanding of these cultural spiritual beliefs especially in the context of suffering, the message of the gospel can be misinterpreted or directly challenged.

Example codes: Coding and end-of-life care, patients do not ask about suffering, spiritual fulfillment, biblical virtues and ethics, understanding of a theology of health and suffering, spiritual differences.

Theme 6: Faith in God’s sovereignty conflicts with patients’ suffering, high mortality, and an urgent need for one’s clinical services.

HCMs feel and have a personal sense of Christian duty to relieve suffering and provide life-saving care. Yet, the limitations and challenges inherent to the mission setting frequently end in poor, often uncontrollable, clinical outcomes despite their best efforts, leading to high levels of morbidity and mortality not experienced in one’s home culture. This leads to potential conflict in understanding God’s sovereignty alongside a strong sense of personal responsibility and cultural fatalism when dealing with negative outcomes.

Example codes: Saving lives, advice from experienced missionaries, spiritual guidance, emphasizing God’s sovereignty, addressing aspects of fatalism, gratitude over tasks, relying on local believers, and forgiveness between colleagues.

Theme 7: Strong sense of obligation regarding work responsibilities conflicts with time for family and personal needs, spiritual growth, and wellness.

Healthcare missionaries typically serve in multiple roles, often including leadership roles. They have a strong sense of responsibility, coupled with a strong work ethic. They see themselves as the primary person to carry out those responsibilities leading to porous professional and personal boundaries. Family responsibilities are also recognized as a priority, producing a tension between carrying out one’s calling in the clinical setting alongside one’s calling in the home. Some missionaries with families were able to use the home as a refuge from work pressures, with some utilizing specific rituals to signal the end of the professional role and the beginning of the family role. Others expressed the opportunity to temporarily leave the field through a vacation or furlough as a type of boundary.

Example codes: boundaries not listed, individualistic approach to work-life distinction, vacations, prayer, loneliness.

Moral injury results from being party to actions that conflict with an individual’s moral values. The objective of this study was to identify the potential situations that might lead to sustained moral conflicts by exploring clinical, cultural, and spiritual characteristics informing those situations. By exploring these characteristics, opportunities can be developed for supporting healthcare missionaries in preventing or recovering from moral injury.

Figure 1, developed by the authors in response to the data and literature, describes two pathways resulting from potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs). One pathway represses the experience or associates the experience with shame. This pathway leads to resentment, isolation, and blaming self, others, and/or God. The alternative pathway describes a process of identifying the injury and validating the experience with one’s social support system, faith network, or mentors. The individual aligns the experience with reality in the culture, truth from God’s Word, and validation by trusted individuals. The pathway can lead to growth and greater trust with others, self, and God. Each theme can be viewed through these pathways to identify and strengthen or change a missionary’s response to the PMIE. Two factors that might influence the perception of PMEIs could be an individual’s prior experiences and training.

Figure 1: Potentially moral injurious experience pathway to growth or blame

Theme 1: Deep sense of personal responsibility for patients conflicts with unfamiliar medical conditions, unexpected requirements, and inadequate resources to carry out that responsibility.

HCMs enter the field abiding by certain care expectations learned during their training. Most of the participants interviewed described a situation that not only required adaptation but a whole new set of skills. It often led to a feeling of frustration as they were faced with new or unknown care expectations and minimal resources to learn them or carry them out. This also meant that the “best care possible” was neither possible to achieve, nor necessarily approved by the local medical system. This could lead to feelings of confusion and frustration for not being able to contribute despite their extensive training.

Another area of moral injury may be found in the difference in conflict styles between individualistic and collectivist cultures. American culture values individual action and responsibility, favoring a conflict style of direct confrontation. However, many host cultures have a conflict style of reflecting a more collectivist approach, in which a relationship is prized and confrontation is more indirect. As one missionary stated:

I told him about the dishonesty and money. I told him about the lack of actual care for people, you know [Country X] is the warm heart of Africa and people care about people better than anywhere I’ve ever been. … But they care about people deeper than I’ve ever seen before. …People that have nothing will go and help the next person that has nothing, but it didn’t correlate in the way they give medical care…

When no functional pathway exists for addressing the conflict, injury remains, and the missionary may experience the consequences of moral injury.

The opportunity for growth in this area is recognizing the “different world” context and learning from the providers who understand the common stresses of new HCMs in their setting. This involves setting up clinical and administrative structures that require introductory and continued learning for HCMs. A part of the learning could connect the missionary to a local chaplain to understand cultural beliefs and new expectations of whole-person care. Applying the moral injury model for HCMs, the alternative pathway leads to self-blame and shame in the early stages of the individuals’ service. Healthcare missionaries may also force their expectations on host colleagues. The missionaries might expect that all providers in the facility see their work as a calling. Instead, many consider their work to be simply a career, and their spirituality is lived out in other areas of their life. This also impacts differences in the care being provided. Understanding such differences is expressed by one comment:

It’s not that they want to provide subpar care. I think that they don’t have a category for considering how human dignity and caring for patients the best that you can be done differently. I think it’s wrong for me to interpret that as national providers caring less for their patients. So, I just say that you know the longer I’m there, the more I realized what thoughtful people they are who haven’t had [the] opportunity in the same way that we have. And I think they do have a deep desire to serve the Lord and honor Him and all that they do, and they may just not have the categories, the training, the expertise, or the theological framework for considering that differently.

Another means of growth in the setting of different cultural conflict styles may found in ethics review boards. Such boards were suggested as helpful in resolving conflicts in seven interviews.

Themes 2: One’s own cultural values of leadership conflict with the cultural values of leadership in the host community.

Western HCMs desire to serve with humility and personal freedom yet were sometimes found working with cultural authoritarian systems that limit personal freedom in decision-making. According to some participants, when they served under highly authoritarian leaders, they felt their judgments were compromised, service became work, and the desire for excellence was reduced to the status quo, with minimal patient/family autonomy. Yet, this can also be accompanied by cultural bias or even unintentional or intentional racism between and within national ethnicities working side-by-side in a health mission setting.

[Country X] is very similar in their racism, their tribalism. And I think that by treating our hospital administration as second-class citizens we are affirming their racism. White people are more important, more powerful, more capable than them. So, staff development, I think, is a growth area.

The missionary desires to be a good servant and service provider yet can feel betrayed by the properly appointed leadership, whether local or expatriate. This sense of betrayal alongside the provider’s responsibility for the patient’s wellbeing can lead to a sense of helplessness and moral injury. Perceived inefficient decision-making structures and micromanagement lead to a feeling that individual agency is not recognized. When a missionary is told “No,” it can be felt as though they are not seen, which is challenging based on what they have sacrificed to be a missionary. The sense of volunteerism and service may fade, resulting in a loss of influence, trust, and belonging. HCMs expressed frustration with differences across three areas of human resources, staff development, and finances. For example, a missionary was frustrated when the human resources department failed to discipline a grossly underperforming colleague. This leads to questioning his/her own scope of work and his/her willingness to extend outside his/her scope to cover for the colleague. Several missionaries shared this frustration:

So, I think responsibility is probably a big area of cultural difference in that I’m used to a medical culture where individuals take responsibility for their actions and…are ethically and legally responsible for what they do. And, as such, have … a sense of vocation attached to their work that isn’t there in the same way, in the context that I work in.

…when people are doing a thing that is wrong, there’s kind of no bite to any of the management.

What I didn’t appreciate was when people would just have excuses for not doing the work. Or disciplining those who did not do what their job descriptions said they should.

HCMs can experience growth from this conflict by identifying their own assumed cultural expectations and realizing that these expectations might not be the best practices in their new cultural setting. Open, honest, grace-filled discussions with local colleagues may be helpful in understanding both cultures’ deeply held moral values and addressing this area of moral injury. The discussions should be initially facilitated by a trusted colleague who can guide the HCM toward growth goals rather than resentment when values conflict.

Theme 3: One’s need to appear professionally competent (vocation) conflicts with feelings of personal inadequacy and incompetence.

HCMs are well trained for the setting of Western medicine. However, in the mission context, they commonly encounter medical, cultural, or social conditions for which they are unprepared and may feel inadequate, ineffective, or incompetent. Their sense of value is minimized because of the unknown conditions and care strategies related to Theme 1. The characteristics of being a competent physician have shifted in different contexts and the healthcare missionary must understand their calling alongside colleagues who might see their service as “work” and a “career.” Healthcare missionaries often have excellence as a value yet are bound in their ability to achieve excellence in their calling within the mission context. This can lead to confusion in identity, service, and faith. Wendland (2012) highlights this difference among Western medical students studying alongside Malawian counterparts highlighting the perception of learning “global health” versus “local health.”15 When the missionary’s identity is based on vocation, and he/she cannot perform according to his/her professional or ethical standards, he/she feels inadequate, incompetent, and ashamed.

At a spiritual level, this type of conflict may lead to growth when the HCM is led to define their value as an approved son or daughter of God rather than defining their value by work. In one respect, the HCM experiences a “death” to one’s identity in their career as their calling to transition to a new identity:

So there’s the death to my career, and the death of my daughter. And then the death of my, what do you call it, ministry. Just so the constant identification that I have with, you know, anything other than Jesus…

Lord show me my identity in you and how that is the only thing that’s important, and all these other things just fall into place.

And another stated:

I think over time, you realize there’s no perfect missionary, no perfect doctor, and no perfect missionary doctor. Because the nature of the beast is that you know it exposes your shortcomings.

Theme 4: The professional value to practice within one’s training and competence conflicts with others’ desire for the HCM to practice beyond those limitations.

HCMs are often faced with situations in which the needed care is outside his/her scope of practice. They are caught in a dilemma in which they might cause harm by attempting to provide care for which they are not trained or might allow avoidable harm by failing to try. In such a dilemma, whenever harm occurs, moral injury may follow. The expectations of the HCM may be different from the expectations of national providers and HCM leaders, leading to conflict and potential further injury. When there is a situation that is clearly a violation of practicing outside of one’s scope, the pathway to resolving it can be uncertain, leading to feelings of despair and disorientation.

I think the kind of dilemma that you run into is that it’s an unmanageable situation to deliver the standard of care, culturally, I expect of myself.

I got very frustrated with her, and verbally expressed my frustration in a way that was unhelpful. And whilst the things that I was trying to express may have been entirely accurate, they certainly weren’t expressed with the degree of love which they should have been. And so, I’ve apologized for that, and that was very well received. I think apologizing isn’t something that people do a lot of in [Country X].

Growth in this theme can happen by developing a group consensus on the practice of attempting care outside one’s training. This group may consist of long-term mentors and coaches who understand the local situation, local colleagues, mission organization leaders, hospital leaders, and patient representatives. Such a group could facilitate processing, reflection, forgiveness, and recovery from ethical conflicts, as well as sharing spiritually healthy disciplines with national colleagues. Establishing a formal board or ethics committee to consider, collectively, how to resolve specific situations can help relieve the pressure from the HCM and provide a support system in working through such decisions on a regular frequency.

Theme 5: The desire to share a message of God’s love conflicts with an enormous demand for clinical services and the extent of patients’ suffering.

Many HCMs enter the mission field to share God’s message of love as a form of evangelism. As one participant stated:

These are people who have just never heard and so … just a simple “would you mind if I told you the story of Jesus?” [from] one of our evangelists on the team can lead to really deep conversations. So that, those were probably the most gratifying times.

Several of our missionary participants expressed difficulty in dealing with the extent of suffering that they encountered in their patients. Some of the participants especially struggled when trying to explain God’s role to their suffering patients.

And because you need to recognize that none of this, when it comes to suffering, or even conflict or bad outcomes…was God’s plan…This happened because of us.

Few of the participants reported feeling a sense of purpose in suffering. The conflict in having a value of evangelism and yet feeling doubt over God’s love in this context can lead to a sense of betrayal as a source of injury or moral confusion. Further, several of the participants stated that their patients tended to be fatalistic regarding their illness and suffering.

[People in Country X] are very fatalistic. This question does not come up as they are generally accepting that life involves pain.

Again, it’s a fatalistic society. It happens, that’s it. And so, it’s actually not a question of my culture. People die; that’s God’s will. Horrible outcomes happen, that’s God’s will. So, it’s actually not something that we do because that’s life. Life is hard.

The overwhelming volume of patient care demands tended to crowd out spiritual interactions with patients for several of our participants. They wanted to prioritize evangelism and spiritual teaching but found themselves prioritizing direct patient care. This led to feelings of guilt, regret, and powerlessness.

Regarding growth opportunities related to this theme, several of our participants reported spiritual benefit from the practice of seeking and receiving forgiveness from others and God. Establishing a rhythm of grace through forgiveness can heal relational trauma and injury. Participants expressed the benefit of forgiveness including personal and culturally appropriate corporate expressions of grieving. One participant shared a story of a mentor that guided him in the practice of grieving while relying on the goodness of God:

I’ve done that hundreds of times. Like during the first three months in [Country X], I did that so frequently that I was… not healthy, I would just collapse at the end of the day, crying in a corner. It was actually Dr [name removed], the same surgeon I mentioned, who just really ministered to me and sort of told me his prayer which is similar to what I’ve been saying, and he’s the one who taught it to me, he said [name] I still pray after doing this,—I still cry after all these years of doing this, every time I lose a patient I cry and I pray “Lord, I don’t understand it, I don’t have to, because I know you are good, I know you are love and I trust you” and that prayer is one that I have echoed many, many, many times.

We cannot be so objective, if we’re so objective that we are divorced from feelings of grief, then I think there’s no compassion in us…[we] can’t do both. You know why we cry? So our heads don’t swell.

Another opportunity for growth may be found in more specific preparation for healthcare missionaries regarding a theology of suffering, as well as training in how to engage suffering patients with a message of God’s love in their cultural context and worldview.

Theme 6: Faith in God’s sovereignty conflicts with patients’ suffering, high mortality, and an urgent need for one’s clinical services.

HCMs tend to have a strong sense of personal responsibility for their patients’ medical outcomes, which is consistent with the biblical teaching of loving one’s neighbors as oneself. Many missionaries struggle to reconcile this sense of personal responsibility with the equally biblical teaching of God’s sovereignty over all aspects of life. In the setting of great suffering, high mortality, and urgent medical need, the sense of personal responsibility may lead the missionary to overwork and to bear an enormous burden regarding unwanted outcomes such as the death of a child. HCMs may encounter the death of their patients far more frequently than they did during their training. If they feel personally responsible for the death of their patients, such experiences can lead to disgust, helplessness, or outrage if there is no outlet to place or process the “blame.” Such a mindset may be described as a “savior complex,” in which the healthcare missionary believes that they are truly responsible for the life or death of their patients. In contrast, some missionaries develop a more fatalistic worldview, in which they reject their own responsibility for the outcomes of their patients. Several of our participants expressed a belief in God’s sovereignty but struggled to act on that belief, which required acknowledging the limitations of their own responsibilities. Several participants recognized the need to practice a healthy agency of responsibility in balance with trusting God’s sovereignty:

And even when we were in [Country X], we had very little conflict, but the stakes were higher because in [Country X] I lost about 200 kids per year. I was working a lot more, and the stakes are a lot higher. I definitely wrestled with the moral and ethical issues much more there until I just got to a place…where I could realize, hey, God is sovereign, I don’t have to understand why kids die, and I can’t hold myself to the standard of always making the best clinical decisions because I’m a pediatrician who’s being asked to be a neurologist, a cardiologist, a pulmonologist, and I’m not those things. So, all I could do is the best that I can, and then I pray and I gave it to God.

Ephesians chapter two verse ten talks about that we are his workmanship prepared to do good works which God has prepared in Christ Jesus beforehand. And it really hit me that God prepares us, we’re his workmanship, and God prepares the works themselves. This is him not us. And so, my responsibility is to be faithful to work in those works which [he] has put before me. It’s not to try to do more than that. He has prepared me, and he has prepared the works themselves that I will do. So, I just need to be faithful in that and just put it there.

God is sovereign and he can do what needs to be done and if I can just follow and do what he’s led me to do and what I’m capable of, and where he’s put me…I feel like there may be some people that would feel guilty for the things that they’re not able to do that they know should be done, but I just I don’t feel guilty for those things, because…overall God is the one who’s controlling it and I can’t control everything.

One participant provided a summary of the balance in applying God’s sovereignty to a situation and recognizing the suffering happening without the need to explain it away or ignore it. HCMs may grow by holding God’s sovereignty and human agency as complements rather than dichotomies. This can create tension with the reality that God is sovereign and will produce good within suffering.

I think I would basically try to explain those three principles. That God is sovereign and he is perfect love and perfect wisdom, and we don’t have to understand everything. And honestly… there’s some advantage for us in missions because both [Countries X and Y] people, they are less modernist than we are in their thought processes. And so that resonates with them, I think, for them it’s just like okay, yeah, God is good. I think it’s not a hard sell. I think it’s a lot harder, actually, with Americans, because postmodern thought has entered in, and surely even modernism has some difficulties with that concept, that well, how could, how could that equal good? And that’s what Romans 8:28 says, that bad equals good. Only for those who love the Lord and are called according to his purpose, but that’s what it says, and ultimately that’s what the cross is, right? Like there’s nothing more evil, ever, then Jesus Christ being crucified. It’s the single most evil action that ever has occurred, and if it hadn’t happened, I would go to hell. So, God used it for my good. God used this horrible evil thing, and turned it into this beautiful thing, which is where my hope 100% rests.

Theme 7: Strong sense of obligation regarding work responsibilities conflicts with time for family and personal needs, spiritual growth, and wellness.

Several of our participants described boundaries as protective against ongoing sustained moral injury, but also shared that boundaries were often difficult to establish. Some carried out rituals that separated their clinic time from family time. Others took vacations to leave the physical environment. Overall, the application of boundaries was not as common as they desired. HCMs with families tended to have a higher likelihood of establishing boundaries. The missionaries valued rest, but also valued providing life-saving care, producing a binding situation. When boundaries were enacted, some HCMs felt conflicted because care was not provided, or felt that substandard care was provided by others, leading to guilt, frustration, low trust among team members, and anger. Regarding observing boundaries, one HMC related, “…fear or embarrassment that I feel, which causes anger. And I’d say that happens daily to weekly.” Several HCMs, especially those in the field for seven or more years, stated that they need to implement boundaries for rest and recovery yet found themselves overextending beyond their capacity contributing to lower quality care. This can then lead to unrealistic work expectations and neglect of family. Participants stated:

I might not follow the biblical work ethic, I follow the American work ethic: so work your head off because there’s work to do.

I have all of the pathology of an American surgeon somewhere inside of me, but I think it’s been helpful to realize that I’m not the savior. I’m not the good news that I moved all the way across the ocean, to tell people about.

Regarding growth in this theme, HCMs could negotiate healthy workplace boundaries with their teammates, institutions, and families. Such mutually supported boundaries should help create a holistic support system for the missionary to balance their need for rest with their capacity to provide care with excellence.

It’s a recognition that I’m not God, and I can’t save everybody, and that I can do my best with the gifts the Lord has given me, but I need to release that to God and not let that weigh down on my spirit, because I can’t bring that home to my family, and I can’t bring that to the next patient to take care of--because that leads to bitterness, and resentment, and not serving every patient with joy.

Or, as you learn the culture, you can realize that their work ethic is infinitely better in some ways than ours, they just have different views on how that work is to be done, and when are appropriate times to sit and have tea and when are appropriate times to be at work.

I’m a missionary. And I’m supposed to be reflecting God and if I am angry, short-tempered, not tolerating people because of mistakes, then it doesn’t matter what I’m doing – it doesn’t matter how many people I have saved if I completely destroy the message that I’m supposed to bring.

I believe it’s important to study and do things really well. Otherwise, I think you’re defaming the Gospel to go and offer mediocre care, I think it doesn’t support the Gospel, it doesn’t honor the Lord. That said, to do it in a way that isn’t biblical and says I’m the savior…I have to do all of this, I have to be there 150 hours a week, well that’s not reasonable, it’s not sustainable, it’s not biblical, you probably aren’t in good headspace when you’re actually offering that care, it’s probably damaging to those around you, it’s not a good witness to the people that you are wanting to train or minister to.

I’d still like the idea of wearing a lab coat because when I come home…This disrobing ceremony that I do where I take off my lab coat and I hang it on the hook has always been very symbolic to me. And when our kids were with us, they might, you know, be outside playing or see me come in, and they’d be like “Hey dad!” and I’d be like, “I’m not home yet. I still got my lab coat on.” And then they follow me in and right inside the door there was always a place for my lab coat and they would follow me in, and then there’d be this game where you know, maybe I take my coat off, maybe I’m not, you know, and then I’d finally take it off hang it up and then, I’m home, and they’d mob me or whatever. But even though there’s no kids, it’s still very symbolic to me…I come home and I take my lab coat off. And now I’m home. And that draws a boundary.

Table 3 summarizes the main themes and corresponding values that might be injured and suggested values to highlight for growth.

Demographic data from our study included time served on the field. We anticipate a second analysis comparing the prevalence of themes according to time served. Future research should also build on these results by exploring the relationship between the themes and developing a conceptual model building on the injury/growth pathway. The model could lead to the adaptation of a screening instrument to monitor and assess moral injury among those in the field and upon return.

Strengths of this study include the extensive interview guide that broadly covered clinical, cultural, and spiritual factors associated ethical conflicts and situations among healthcare missionaries. Analyzing the data across all questions allowed the team to observe relationships between all three domains. Another strength is the breadth of specialty areas, time in the field, and regions represented among the participants.

Limitations of the study include the small sample size given the scope of HCM service and the limited number of responses from Eastern Europe and parts of Asia. As noted earlier, the sample size is within recommended ranges for a qualitative study. Most of our respondents were physicians. As such, the perspective of healthcare missionaries from other vocations was under-represented, which may lead to bias. Qualitative analysis is inherently subjective based on the researchers’ personal experiences and training. The analysis and resulting themes should be interpreted accordingly. The study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic and could have influenced the responses

This qualitative analysis identified seven predominant themes of moral value conflict among western healthcare missionaries. These themes can be used to develop programs and practices to prevent and address moral injury before, during, and after serving in the mission field. The themes also provide a foundation for further investigation and development of instruments for measuring and assessing the extent of moral injury among HCMs in the field to appropriately manage and treat this important and ubiquitous problem.

Read informed consent information and obtain verbal agreement. If participants agree, continue with the interview.

1. Number of tours and total years in the field. Which fields?

2. How many clinical hours per week do you usually work when on the field? How many administrative hours per week?

3. Specialty area.

4. How long in between completing your training and entering the mission field?

Medical practice dissonance/unity (leadership, conflict management)

5. What do you appreciate about being in your role? What has helped you appreciate your service?

6. On average, describe how do you typically feel when you are at the clinic? When you are at home?”

7. How often do you have conflicts with local/national colleagues in the following areas (All the time, some of the time, rarely, or never)

a. Regarding patient care?

b. Regarding finances?

c. Regarding work performance?

d. Dishonesty?

e. Work hours?

f. Charity care?

8. How do the expectations of practicing medicine in your country of origin differ with the expectations of how you practice in your country of service? (consider best practices, standard of care, provider responsibility for outcomes, scope of practice.)

9. How do the expectations of hospital leadership in your country of origin differ with the expectations of hospital leadership in your country of service? [Include expectations of government Ministry of Health.]

g. Finances

h. HR

i. Staff development

10. How do you use personal supports such as mentors, pastors, or former teachers to reconcile ethical conflicts in your work?

j. Are these individuals nationals or from your host culture?

k. Have your mentors changed over your time in your country of service?

11. How have you described differences in values between yourself and national providers in your clinical practice or hospital when talking with others?

12. Describe a time when you felt like you failed in your moral obligation to your patients.

13. What additional training would have been helpful to you prior to entering the mission field?

Spiritual dissonance/God’s sovereignty (savior complex, Sabbath, moral injury)

14. How do you use your faith, spiritual beliefs, or biblical understanding to navigate ethical conflicts in clinical care?

15. How would you respond to patients asking about the reason for suffering?

16. What biblical ideas guide your work ethic?

17. How often do you engage in the following in in a typical week:

l. Bible reading,

m. Other spiritual reading,

n. Prayer

o. Attend worship services

p. Attend a small group Bible study

18. Have you ever done the following:

q. Asked for or gave forgiveness to a national colleague

r. Shared a personal spiritual or emotional burden with others on your team

s. Cried by yourself or with other team members over the death of a patient

19. What practices help you maintain boundaries for your life on the field?

Cultural dissonance/compassion (charity care, competencies, conflicting values)

20. How did you come to learn about the local culture related to work expectations?

21. How did you respond when ethical conflicts related to patient care were not resolved?

22. Thinking about the leadership of your hospital or station, what leadership practices have you appreciated or which have you found difficult from expatriate or national leaders?

23. How does the following statement make you feel: “I often disagree with my colleagues about charity care or helping patients that are not able to pay.”

24. How often do you experience the following (daily, weekly, monthly, almost never, never)

a. Guilt over inappropriate care or care you were not able to provide

b. Frustration over inappropriate care provided by someone else on your team

c. Sadness/anger over not knowing how to care for a patient

d. Satisfaction over progress toward a goal

e. Gratitude for something God has done through me

f. Joy in my daily clinical/administrative tasks

Would it be okay to contact you for clarification or to follow-up with additional question as they come up during the analysis?

We have talked about challenging topics. In a follow-up email, I will provide links and contact information for additional resources from CMDA and MedSend.