ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Christian milestones in global health: the declarations of Tübingen

Steffen Flessaa

Abstract

The conferences on Christian Health Care which were held in Tübingen (Germany) in 1964 and 1967 set a foundation for understanding the role of Christian health care services in the healing ministry of the church. However, it has to be asked whether the findings of these conferences are still relevant for the 21st century. In this paper we analyze the changes of the global health care provision since the declarations of Tübingen. Based on this analysis we argue that Christian health care services are still called to contribute to the struggle for health and healing worldwide, in particular for the vulnerables. However, this requires a thorough portfolio analysis of our services rendered and a focus on spirituality in particular of the leadership.

Introduction

The healing ministry of the church covers all dimensions of human existence: body, soul, and spirit. Thus, Christians are called to holistic healthcare as an essential of their faith.1 Consequently, Christians have almost always been engaged in healing, caring for the sick, and establishing institutions of charity for the poor and needy. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, church-based hospitals were founded all over the world, frequently growing to major institutions with thousands of co-workers.2 For many people, Christianity and hospitals became almost identical, particularly in the former colonies where mission hospitals frequently constituted the back-bone of diaconal work of the new churches.3 Although mission hospitals could never cover the entire population, they were an essential element of the healthcare sector in most regions of the world, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.4

However, the concept of medical-mission-based big hospitals where “white doctors” provided western medicine was challenged. In May 1964, representatives from protestant mission societies gathered in the little town of Tübingen, Germany, to discuss the “Healing Ministry in the Mission of the Church.”5 The results of “Tübingen I”(19th – 24th of May 1964) and of the subsequent “Tübingen II” (1st –8th of September 1967) conferences had a major impact on the self–perception and the strategies of Christian healthwork.6 Although the majority of statements stipulated at these conferences were not completely new, the declarations from Tübingen gained an unprecedented momentum and led to the foundation of the Christian Medical Commission (CMC), which had a strong impact on the development of the Primary Health Care paradigm of the World Health Organization.7,8

Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) titled its World Health Report as “Primary Health Care –Now more than ever.”9 With this report, WHO clearly underlined that the principles of Primary Health Care (PHC) stipulated in Alma Ata had become increasingly relevant, even in the 21st century. Naturally, some concepts of PHC have to be adopted to the “challenges of a changing world.”9 However, the main paradigms and objectives remain unchanged. This confirmation of PHC by the WHO strongly contradicts the poor perception of the declarations of Tübingen by the world-wide churches and the mission societies in the 21st century where the knowledge of Tübingen is almost lost. Even the Christian Medical Commission dissolved into the World Council of Churches, losing almost all relevance for the medical field. Consequently, one has to ask whether the declarations of Tübingen are merely an historic event without any relevance for the future of Christian healthcare services in the 21st century. Under which conditions could we state “50 years of Tübingen –Now more than ever”? And what must change in Christian healthcare and not only in resource-poor countries so that they can continue fulfilling their call in the future?

This paper argues that the core statements of the declarations of Tübingen I and II are not only historical events but of high relevance for the future of Christian healthcare services if they are transferred to the 21st century and adapted to the new conditions. For this purpose, we will present the history of Christian health services from an economic perspective. We are aware of the fact that this is only one dimension of Christian health services, but one that might be eye-opening for the relevance of the history and the perspectives of the future. Consequently, in the next section, we will discuss the basic declarations of Tübingen and Alma Ata. Afterwards we will analyze the development of Christian health services, focusing on resource-poor countries from early colonial times to the new millennium. The paper then closes with some conclusions.

Fundamental Declarations

The declarations of Tübingen and Alma Ata were of high relevance for the development of Christian health care in the second half of the 20th century. In this section, we describe the concepts.

The quest for health and healing: Tübingen I and II

After World War II, the traditional approach of providing church-based health services in the colonies or newly independent countries was criticized for its paternalistic approach where western mission societies, missionaries, and (white) doctors knew what their patients needed, as the patients were begging for help.10-18 At the same time, it became obvious that Christian healthcare services were not nearly as successful and sustainable as missionary societies had always believed. As a reply to this critique, directors of major protestant mission societies gathered to analyze and discuss their work in Tübingen, Germany, from the 19th to the 24th of May 1964 (Tübingen I). They realized that their services were not reaching the majority of people so their system was very unjust. McGilvray, the former director of the Christian Medical Commission (CMC), described the situation with these words: “. . . these church-related institutions, together with all the other available facilities of Western medicine, were reaching only 20% of the population in these countries and were thus sustaining a grave injustice to the 80% who remained deprived of any services at all.”19 In addition, they realized that due to technical progress, the costs of medical treatment had increased tremendously in the existing institutions, so that even the little that was being done could not be sustained.6

Table 1 summarizes the most important findings of Tübingen I by citing the most relevant headings of the declaration (shortened by the author).

Table 1. Most important findings of Tübingen I6

1) The Christian Concept of the Healing Ministry

- The Christian Church has a specific task in the field of healing.

- The specific character of the Christian understanding of health and of healing arises from its place in the whole Christian belief about God’s plan of salvation for mankind.

- The Christian ministry of healing belongs primarily to the congregation as a whole and only in that context to those who are specially trained.

- The Christian ministry of healing as exercised by the Church is subject to Him who is the Lord and Head of the Church and to the continuing guidance of the Holy Spirit.

2) The Role of the Congregation in the Ministry of Healing

- In Scripture, both sickness and healing are distinctly corporate experiences.

- All healing is of God.

- Within this understanding, it follows that the congregation has a central and responsible role in the healing ministry.

- The congregation has a very special responsibility for those of its members who are engaged in medical institutional work.

- The congregation should encourage its members to enter the healing professions.

3) The Healing Ministry in Theological Training

- A Christian understanding of healing is already implicit in theology.

- In spite of this, no explicit teaching on the Christian understanding of healing is given in most of our theological colleges and seminaries.

- It is imperative that teaching should be given on this subject in all our theological colleges and seminaries.

- The department of theological education in which the practical significance of the ministry of healing can most effectively be made explicit is that of pastoral theology.

- The laity also needs training in the ministry of healing, and this must be kept in mind in theological training.

4) The Training of Medical and Para-Medical Workers as a Task of the Church

- Continuing efforts to improve the professional quality of medical work and the teaching of co-workers need to be recognized as an integral and essential part of any form of medical evangelistic service.

- The Consultation recognizes the churches’ responsibility in medical education.

- It is urged that immediate consideration be given to the extension of intern and residency training facilities in existing church-related hospitals.

- The Consultation believes that nursing-education should be carried on at every level.

- Similar consideration should be given to the training of para-medical workers.

- Special attention needs to be given to the selection of the chaplain and specialized training.

- Involvement in organized Christian medical work must be regarded as a specialty in itself.

- The Church should encourage suitably qualified members to accept teaching positions in universities, medical colleges, nurse schools, and similar secular institutions of learning as a special challenge to Christian witness in teaching.

5) The Institutional Forms of a Healing Ministry

- It will be necessary to study first the role of the medical institution within this context and secondly to see how far other forms of medical service are relevant and necessary.

- We must first confess that the medical institution and the church, on the national and more particularly on the local level, have traveled too often in separate directions. While the hospital or clinic may have substantially aided in the initial creation of a congregation, it has usually failed to commend itself as a continuing expression of that congregation's healing concern.

- The time is long overdue for the complete integration of the hospital and clinic into the life and witness of the Church . . . Where there appears to be no evidence or potential understanding of this integration of healing function, the continuance of the institution must be seriously questioned.

- The size of a medical institution should never exceed what is necessary for its established purpose or the capacity of the total Christian community supporting it and ministering through it.

- We recommend as pilot projects within selected hospitals the initiation of a team concept of therapy, wherein the physician, nurse, psychiatrist, and pastoral counselor should unite to treat the patient in the totality of his sickness.

- Other forms of service, through which the Church should continue to express its healing ministry, lie in the fields of leprosy, tuberculosis, care of the chronically iII and aged, rehabilitation, psychiatry, and maternal and child health.

- The pattern of institutional therapy has too long prevailed in the Church to the detriment of the intimate relationship between patient and doctor in the general practice situation. The healing congregation might well involve its doctor members in this new relationship and challenge their response and commitment.

- The Church must always recognize that it can never meet all of need and should regard new avenues of service as demonstrations of how need should be met.

6) The Relationship of a Christian Healing Ministry to Government

7) Joint Planning and Use of Resources for the Healing Ministry

8) A Continuing Program of Study and Work

- The first is an effective gathering, analyzing, and making generally available the very large amount of work in survey and study that has been done and is in progress around the world.

- b) The second is the encouragement of study and survey at local, regional, and international levels.

- c) The third is the carrying out of pilot and experimental projects in an integrated program of healing.

For the topic of this paper, the most important result of this consultation was the insight that mission hospitals practiced a type of medicine that was not in line with the biblical understanding of salvation and healing. Instead of placing the healing mission of the church on the shoulders of a few medical experts, the entire church was designated as the “healing body of Christ” to fulfill the healing ministry.20-22 Existing hospitals, they concluded, “were, basically, repair facilities which did little if anything to remove the causes of sickness or to promote and maintain health.” It was realized that medical mission must include preventive services and that God is interested in holistic healing, in shalom, including problems of guilt, suffering, and death.23,24 Therefore, the Declaration of Tübingen I called for the empowerment of the entire church as the healing body of Christ. Everybody in this Church is called to participate in the healing ministry. It was the basic outcome of this consultation that Christian healing was only possible in participation with all stakeholders.

The declaration of Tübingen I was received well in developing countries. Several local consultations followed, and in 1967 (Tübingen II, 1.-8. September 1967), a new, community-based approach was declared obligatory for church-related healthcare services.25-27,28 The innovative work was coordinated by the newly founded CMC. From 1973 to the early 1980s, this institution was in close contact with the World Health Organization, highly influencing the development of the Alma Ata Declaration.8

Health for all by the year 2000: Declaration of Alma Ata

Some 25 years after its inauguration on April 7, 1948, the World Health Organization had to recognize that the most important health problems had not declined. On the contrary, financing the existing health services had become more and more difficult as technical progress in medical technology and pharmacology made “health for all” more and more expensive.29 In a search for new solutions, the Director General of the WHO, Halfdan Mahler, recognized that the decisions of Tübingen were relevant for all health care systems in developing countries, not only for church-related services. The concept of Primary Health Care (PHC) that was discussed and approved during the World Health Assembly in 1978 can be interpreted as a secular advancement of the Declarations of Tübingen.30

Primary healthcare is based on the tradition-al concept of hygiene but enriched by a health-political dimension and a strong element of participation.31-34 Primary healthcare is a conception of health policy, i.e., it is not a level of healthcare, but a comprehensive philosophy of healthcare underlying all decisions in the health field. It is fundamentally oriented to the needs of the community and intends to include the community in all processes of determining objectives and means of healthcare. The stake-holders of the community are to accept responsibility for their own health, so that institution or program-based healthcare becomes a community based healthcare (CBHC). Thus, PHC and CBHC introduce the concept of participation as an essential dimension of the health care system.

The strong community approach was rejected by many institutions and policy makers. Some saw it as expression of a left-wing political movement, as Art. III of the declaration refers to a “New International Economic Order,” and Article X states that high military expenditure is a major reason for poor health. Werner & Sanders write: “Many of the principles of Primary Health Care were garnered from China and from the diverse experiences of small, struggling non-governmental Community-Based Health Programs (CBHP) in the Philippines, Latin America, and elsewhere. The intimate connection of many of these initiatives to political reform movements explains to some extent why the concepts underlying PHC have received both criticism and praise for being revolutionary.”35

More important was the criticism from health specialists stating that PHC was utopian.12-15,36-40 They called for strict priorities, in particular, a concentration on vertical programs to fight childhood diseases. Contrary to the original Comprehensive Primary Health Care (CPHC) concept of the WHO, the Selective Primary Health Care (SPHC) and the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI), in particular, could work without strong community participation.41,42

The failure to implement the comprehensive primary healthcare concept in most developing countries has been frequently discussed and has many reasons. Flessa developed an innovative model with several barriers to implementation.43 Firstly, he describes that innovations (such as the revolutionary content of the Declarations of Tübingen and Alma Ata) have only a chance to be adopted if the existing system is perceived as unsatisfactory. Otherwise, decision-makers will try to improve the existing system instead of accepting the new one. If donors continue supporting the existing curative healthcare system, it is likely that this steady flow of funds stabilizes the old system and blocks the adoption of the new. Secondly, the higher the costs of an innovation are, the less likely it will be adopted. The costs of introducing CBHC-systems were frequently underestimated. Thirdly, the more decision-makers seek a quick win, the less likely they will invest healthcare resources in prevention and primary care. Some measures of CBHC will only see a return in investment in decades (e.g., vaccinations); whereas, the results of curative care are always visible in the year of investment. This is, fourthly, associated with risk-perception. Innovation always involves risk, so that it is generally true that the more risk-averse people are, the less likely they will accept an innovation. Finally, leadership style determines the likelihood of adopting primary healthcare innovation. The more freedom superiors grant to their subordinates, the more likely they will experiment, seek for innovations, and find new solutions. However, neither mission societies nor churches in developing countries are well-known for a participatory leadership style that encourages their members to take risks and think beyond existing structures.

Consequently, Flessa concludes that it was very unlikely that the Declarations of Tübingen and Alma Ata would be welcome by Christian healthcare services and that the original objectives of Tübingen and Alma Ata have – in the years after introducing selective primary healthcare – almost disappeared from the agenda of healthcare policy makers. Freedom as the fundamental right to participate in all processes with impact on one’s life was reduced to the freedom to choose between different providers. Participation of the local population in setting priorities in healthcare, in designing healthcare services, and in controlling institutions and programs has almost disappeared from the political, as well as from the research, arena.

However, the declarations of Tübingen and Alma Ata are the two basic foundations of Christian health care services. In order to understand their relevance for church-related healthcare, we have to see them in their historic perspective. The next sections will sketch the developments in order to analyse the relevance, in particular, of Tübingen I and II for the future of Christian health services.

Colonial and Early Post-Colonial Time

The 19th century saw an increased awareness by Christians in Europe and Northern America for the evangelistic and diaconal call of the Church. In many countries, hospitals, homes for the poor, and mission societies were founded and started their charitable work. In particular, mission societies planted health stations and, later, hospitals in the countries of their work. The majority of Christian healthcare institutions in these regions were built in rural areas; whereas, colonial powers frequently concentrated on towns of strategic importance. In most rural places, churches had a natural monopoly for “modern” health care. “Natural” here means that the next provider was so far away that the catchment population of the healthcare provider had actually no chance to reach the alternative provider. The maximum distance of travel was lower than the distance between the institutions.

As a consequence, Christian healthcare providers did not have to justify their existence by any other characteristic than by their presence. Christian healthcare services in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia were “good” simply because they were there. If they had not existed, nobody else would have been there. In case of a monopoly, the provider did not have to be better than others, and the provider did not have to find reasons why he/she provided services. There was plainly no alternative.

The declarations of Tübingen came at a time where the contribution of Christian healthcare to the health of the population was not challenged. During the conferences, nobody questioned whether there was a need for Christian healthcare services in these areas, as they were natural monopolies. The delegates of the conferences were aware of the fact that the newly independent states and their governments would start building-up a “safety net for the poor,” but at the time of Tübingen I and II, there was hardly any competition in the healthcare field.44 The economic problems that they saw, such as increasing costs of medical equipment and drugs, were strong forces behind the declarations of Tübingen, but they had nothing to do with local competition for patients.

Late 20th Century

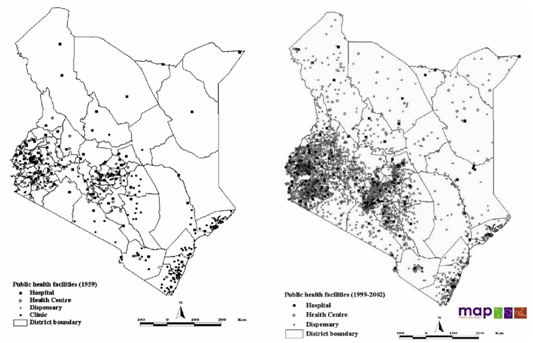

Towards the end of the 20th century, the situation in almost all parts of the world changed. Figure 1 shows the development of public health facilities in Kenya between 1959 and 2002. It is obvious that there are some areas where a healthcare facility still has a natural monopoly based on distances. However, these are in sparsely populated regions. The vast majority of Kenyans have a choice of provider. Christian healthcare providers have lost their monopolies almost everywhere. Government facilities cover nearly the entire country, and in many cases, Christian and government facilities are within walking distance.

Figure 1. Public health facilities in Kenya (1959 and 2002).45

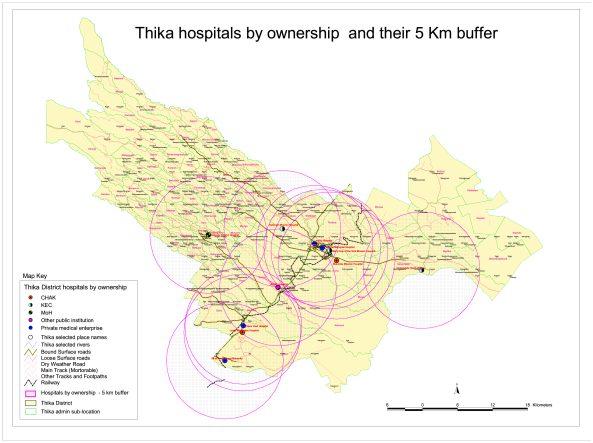

Figure 1 does not include private for-profit healthcare providers. The 1990s and the new millennium have also seen a strong rise of these institutions. Figure 2 shows that governmental, Christian, and private for-profit providers are strongly competing in the Thika district, Kenya. For a long time a few private providers had offered their services to the rich minorities in major towns. They were no competitors for Christian service providers, as they had completely different target groups. However, the situation has changed dramatically. The poor frequently cannot afford Christian services anymore and seek help elsewhere. As Flessa shows, Tanzanian Church-based healthcare providers frequently have to charge higher fees than government institutions to recover their costs so that the poorest tend to avoid Christian institutions.43 At the same time, private providers have discovered the poorer strata as their clients, most likely not the poorest of the poor, but, in particular, the “working poor.” That is, many private for-profit healthcare providers have opened their dispensaries, pharmacies, and hospitals, even in rural places, for the non-rich, and they compete directly with Christian healthcare services. The time of monopolies for the majority of Christian institutions is over, the era of “Business of Health in Africa” has come.46

Figure 2. Hospitals in Thika District, Kenya (2008).47

The loss of the monopoly challenges the economic foundation of many Christian healthcare providers. In the years after 1990, several of them were poorly utilized as patients moved to the improved governmental providers or to the fast and user-friendly private providers.48 In many African and Asian countries, Christian institutions maintained a monopoly of quality for some time as they had access to international drug markets through their international connections. However, through liberalization and economic strengthening in several of these countries, governments and private for-profit providers could offer the same quality of services in the new millennium and, thus, taking the last visible reason of exceptionality of Christian healthcare providers.

However, the loss of the monopoly position impacted more than the economy. The most crucial impact was that Christian healthcare providers had to justify their existence. Simple presence does not any longer justify existence as it did decades ago. Towards the end of the 20th century, governments, national and local societies, as well as the international and donor community started asking for good reasons for the existence of these Christian institutions. In a market economy, and most countries have moved in that direction even in the healthcare system, any market element must have a comparative advantage to survive. It can be cheaper, have a higher quality, or provide a rare utility component. Christian healthcare institutions are no exception; they are asked to justify their existence by lower fees, better quality, or a dimension of services that cannot be offered by other institutions.

Another important change happened in the international policy arena. The “natural” partner of the Christian Medical Commission (CMC) was the World Health Organization, both residing in Geneva. Indeed, CMC gained quite some influence on the WHO. However, as shown in section 2, a few years after Alma Ata, UNICEF adopted the concept of “selective primary healthcare” which degraded the original concept of “comprehensive primary healthcare” to a few target groups and diseases. A few years later, the World Bank entered the arena as a major player. The 1993 World Development Report “Investing in Health” became a milestone in international health policy.49 This report not only called for more cost-effectiveness in healthcare, but it moved the“philosophical” and value-based discussion in a technical direction with the concept of disability adjusted life year (DALY).50 The DALY reduces human health purely to its physical dimension, miles away from the Tübingen concept of wholeness. The World Bank became the prime mover in global health and not WHO, where mission societies or Christian healthcare services had had a major influence. The WHO reacted with accusations, but finally accepted and adopted the World Bank concepts.

Although the World Health Organization came back to the international policy arena in the late 1990s under Gro Harlem Brundland, the Christian community has had very little influence in the subsequent developments. Neither the “Joint Commission on Macro-Economics and Health” nor the development of the “Millennium Development Goals” was systematically influenced by the Church or Church-related institutions.51 It is a matter of fact that individual Christians were in the relevant committees, but they did not bring the value-based discussions of Tübingen into these committees. In particular, the MDGs clearly focused on the physical dimension of life without any reference to social or spiritual existence. In the new millennium, we might be closer to “Health for All,” but the World Bank, UNICEF, and WHO concept of “health” is definitely not the concept of Tübingen I and II.

Universal Health Coverage and the New Millennium

This development contributes the concept called “Universal Health Coverage” (UHC). The concept itself is not new, but it gained political relevance in the new millennium. The World Health Report 2010 was titled “Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage.”52 Within the next few years, a number of conferences on UHC were held in Mexico City (Political Declaration on Universal Health Coverage 2012), Bangkok (Statement on Universal Health Coverage 2012), Tunis (Declaration on Value for Money, Sustainability and Account-ability in the Health Sector 2012), and the UN-resolution on December 12, 2012, “Transition of National Health Care Systems towards Universal Coverage,” all accepting UHC as a major target of all healthcare systems.

WHO defines UHC as “ensuring that all people can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.”53 Evans, Hsu, & Boerma express it in other words: “Universal health coverage is the obtainment of good health services de facto without fear of financial hardship.”54 Consequently, UHC is not a revival of “Health for All by the Year 2000,” but a focus on healthcare provision and social security.

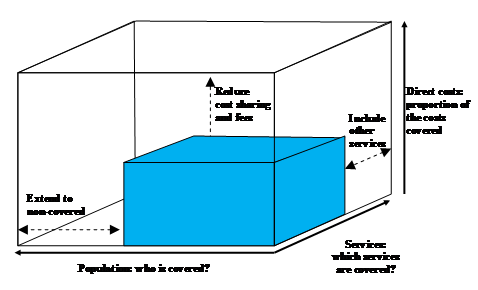

Figure 3 shows the dimensions of UHC. The concept implies that all members of the society should have a right to receive a comprehensive package of healthcare services at affordable prices. It is generally accepted that UHC will only be achieved by the establishment of some form of social health insurance. Local and small-scale initiatives, such as the Community Based Health Insurances frequently supported by churches, will not suffice.

Figure 3. Universal Health Care-cube.52

The concept of UHC has been criticized for its strong focus on health financing and technical-functional dimensions of health.55 Some critique is inspired by Christian theology, e.g., from I. Illich.56 However, this critique has had very little impact on the conceptualization of UHC, and it is about to become, explicitly or implicitly, a backbone of the post-MDG period. We can clearly state that Christian healthcare services have had hardly any influence on this development. This is particularly disappointing, as UHC definitely falls short of the holistic concept of health stipulated in Tübingen. UHC could require a stronger focus on health instead of healthcare, but Christian institutions have lost their influence on healthcare policy-making.

In addition, in a number of developing countries, we already see the consequences of social security as an element of UHC. Potential patients obtain insurance coverage. They become clients and customers, not just beneficiaries of good Christians, and they receive a right to choose between different providers. Even the poor, the target group of a number of health insurance projects in developing countries, suddenly have the right to decide where they will go for services. Consequently, the future will see in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia a similar situation as exists in Europe and Northern America already today: Christian healthcare services as normal market partners. From a pure economic perspective, they have lost all exceptionality. They compete with other providers: churches, government, and scores of private for-profit enterprises, and some of them will face the same fate as many church-based healthcare institutions all over the world: after a century of great history, they will go bankrupt and cease to exist. Many of the remaining Christian healthcare providers cannot be distinguished from their private or governmental competitors.57 UHC and social protection led to free choice of providers, and it is not yet known whether people will always continue choosing the Christian provider.

Consequently, 50 years after the declaration of Tübingen, Christian healthcare services are called anew to define their purpose and their distinctiveness. However, today, it is not only a question of defining “a better way to serve the Lord,” but it is also a question of life or death. The existence of our institutions must be justified to save their existence.

Conclusions

Knowledge of the Tübingen declarations among decision-makers of Christian healthcare services is declining. It has to be asked whether these declarations are simply historic events or whether they still have an important message for Christian healthcare services in the new millennium.

A first step in the analysis is to compare the situation of the 1960s with today. The economic conditions of Christian healthcare services at the time of the declarations of Tübingen were quite different from today. Church-related healthcare providers were monopolists without competition, providing existential services for their catchment population within rather simple systems. Today, the situation is already different for the majority of Christian services worldwide. Technical-functional services for the physical dimension of life are provided by many competent competitors. In many locations, pure presence is not a justification for existence anymore.

In Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, there are still Christian healthcare providers with limited or no competition. However, this situation is due to change as soon as these countries are successful in their strides towards Universal Health Coverage and the establishment of social security systems. In particular, as the poorest of the poor are covered by subsidized insurance schemes, beneficiaries become customers with rights, with purchasing power, and with choices. All of these expected developments are positive and should be welcomed – but they challenge the self-perception of Christian healthcare services.

In this situation, the declarations of Tübingen I and II become highly relevant again. Thus, in a second step of analysis, we have to ask anew whether we should be distinguishable from all other providers, what criteria could make us special, and how we can find our place in the health care market. The old search for the “proprium”(Latin: property, what belongs to someone) or distinctiveness of Christian healthcare, as it was stipulated in the declarations of Tübingen, is relevant “now more than ever.” If we do not find contemporary answers to the “quest for health and wholeness,”Christian healthcare services can neither survive nor fulfill their call for healing and salvation.6

Today, there is a great need for a new vision of distinctiveness and spirituality in Christian healthcare services. The findings from 1964 and 1967 can still be guiding principles for the future of Christian healthcare services so that we can indeed state “50 years of Tübingen – now more than ever!” Christians have a unique contribution to give, grounded in the theology of health and healing as well as in the reality of competitive health care markets. But, they have to know their values, their history, and the changes of the demographic, economic, and social environment to make Christian healthcare services functional and sustainable. Future research is needed on the translation of the principles of the declarations of Tübingen for the service portfolio, the leadership, and the spirituality of Christian healthcare providers.

Reference

- Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland. Texte zum Schwerpunktthema: Diakonie, 3. Tagung der 9. Synode der EKD. Munster. 1-6 November 1998. Hannover: Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland; 1998. German.

- Städtler-Mach B. Das evangelische Krankenhaus: Entwicklungen-Erwartungen-Entwürfe [dissertation]. Lottbeck Jensen; 1993.

- Grundmann CH. Gesandt zu heilen. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus; 1992. German.

- Schweikart J. Räumliche und soziale Faktoren bei der Annahme von Impfungen in der Nord-West Provinz Kameruns. Heidelberger Geograph Arbeit. 1992;92. German.

- Newbigin L. Editor’s note. Int Rev Missions. 1964;53: 250.

- McGilvrary JC. The quest for health and wholeness. Tübingen: German Institute for Medical Missions; 1981.

- Church Mission Society. The health of the whole man - a statement on C.M.S. medical policy 1948. London: Church Mission Society; 1948.

- Diesfeld HJ, Talkenhorst G, Razum O, editors.Gesundheitsversorgung in Entwicklungsländern. Medizinisches Handeln aus bevÖlkerungsbezogener Perspektive. Berlin: Springer-verlag; 2001. German. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-56648-6h

- World Health Organization. World health report 2008: primary health care: now more than ever.Weltgesundheitsorganisation; 2008. German.

- Weishaupt M. Krankendienst in Afrika. Aus Vergangenheit und Gegenwart der Leipziger Mission. Leipzig: Leipziger Missionswerk; 1936. [German].

- Gilmurray J, Riddell R, Sanders D. The struggle for health. London: Macmillan Education; 1979.

- Walsh JA. Selective primary health care: strategies for control of disease in the developing world. IV. Measles. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5(2):330-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/5.2.330

- Walsh JA. Selectivity within primary health care. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26(9):899-902. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(88)90408-X

- Walsh JA, Warren KS. Selective primary health care: an interim strategy for disease control in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 1979; 301(18):967-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197911013011804

- Walsh JA, Warren KS. Selective primary health care: an interim strategy for disease control in developing countries. Soc Sci Med [Med Econ]. 1980;14(2):145-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0160-7995(80)90034-9

- Scott RW, Meyer JW. Institutional environments and organisation. Structural complexity and individualism. London: Sage Pub; 1994.

- Heggenhougen HK, Shore L. Cultural components of behavioural epidemiology: implications for primary health care. Soc Sci Med. 1986;22(11):1235-45.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(86)90190-5

- King M. Medical care in developing countries. Oxford: OUP East and Central Africa; 1986.

- McGilvray JC (German Institute for Medical Missions). The quest for health. An interim report of a study process. Tübingen: German Institute for Medical Missions; 1979.

- Wilson M. Exploration in health and salvation. Birmingham: University of Birmingham; 1983.

- Nthamburi Z. The ministry of healing. Addis Abeba: Association of theological institutions in Eastern Africa, Staff Institute; 1990.

- Ram E. Transforming health. Christian approaches to healing and wholeness. Monrovia: University of South Africa; 1995.

- Fountain DE. Health, the Bible and the Church. Wheaton: Billy Graham Center; 1989.

- Scheel M. Kann Glaube heilen. Breklum: Breklmmer Verlag; 1988. German.

- Makumira consultation, health and healing, in the report of the Makumira consultation on the healing ministry of the church. Soni, Tansania; 1967.

- Gimbi AL. Clinical pastoral education and hospital chaplaincy in East Africa, in Theological Seminary of St. Paul. St. Paul, MN: Theological Seminary of St. Paul: 1975.

- Christian Medical Board of Tanzania. Proceedings from the Tanzania church consultation on PHC, June 10-15, 1985. Dar-es-Salaam. Christian Medical Board of Tanzania; 1985.

- McGilvray JC. Der verlorene Gesundheit - das verheißene Heil. Stuttgart: Radius; 1982. German.

- World Health Organisation. Organisational study on methods of promoting the development of basic health services. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1973.

- World Health Organisation. Alma-Ata 1978: primary health care. Report on the International Conference on Primary Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 6-12 September 1978.

- Ashorn P, Kulmala T, Vaahtera M. Health for all in the 21st century? Ann Med. 2000;32(2):87-9. http://dx.doi.org/: 10.3109/07853890009011756

- Fendall NR. Declaration of Alma-Ata. Lancet. 1978;2(8103):1308.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(78)92066-4

- Passmore R. The declaration of Alma-Ata and the future of primary care. Lancet. 1979;2(8150):1005-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(79)92572-8

- Romualdez A. Primary health care. Maghreb Med. 1980;20(4):3-4.

- Werner D, Sanders D. Questioning the solution: the politics of primary health care and child survival. Palo Alto: Healthwrights; 1997.

- Parker AW, Walsh JM, Coon M. A normative approach to the definition of primary health care. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1976;54(4):415-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3349676

- Walsh J. New look at health in developing nations. Science. 1987;238(4828):746. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.3672123

- Warren KS. Selective primary health care: strategies for control of disease in the developing world. I. Schistosomiasis. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4(3):715-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/4.3.715

- Warren KS. The evolution of selective primary health care. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26(9):891-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(88)90407-8

- Zwi AB, Mills A. Health policy in less developed countries: past trends and future directions. J Int Dev. 1995;7(3):299-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jid.3380070302

- Basu RN. Expanded programme on immunization and primary health care. J Commun Dis. 1982;14(3):183-8.

- Keja K, Chan C, Hayden G, Henderson RH. Expanded programme on immunization. World Health Stat Q. 1988;41(2):59-63.

- Flessa S. Gesundheitsreformen in Entwicklungsländern. Eine kritische Analyse aus Sicht der kirchlichen Entwicklungshilfe. Frankfurt a.M.: Lembeck; 2002. German. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/20765255

- Brugha R. The private sector: friend or foe of the poor? Africa Health. 1998;Jan 1998:16-8.

- Noor AM, Alegana VA, Gething PW, Snow RW. A spatial health facility database for public health sector planning in Kenya in 2008. Int J Health Geograph. 2009;8:13.http:dx.doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-8-13

- Weltbank. Weltentwicklungsbericht: Investitionen in die Gesundheit. Washington D.C.: Weltbank; 1993. German.

- Ministry of Health. Mapping Study, Thika District, D.o. Planning, Editor. Nairobi: Ministry of Heath; 2008.

- Flessa S. The costs of hospital services: a case study of Evangelical Lutheran Church hospitals in Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 1998;13(4):p397-407. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/heapol/13.4.397

- The World Bank. World development report: investing in health. Washington D.C.: The World Bank Group. 1993.

- Murray CJ. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72(3):429.

- World Health Organisation. Report of the commission on macroeconomics and health. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2001.

- World Health Organisation. Weltgesundheitsbericht 2008. Geneva: Weltgesundheitsorganisation; 2010. German.

- World Health Organisation. Universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/health_financing/en/

- >54. Evans DB, Hsu J, Boerma T. Universal health coverage and universal access. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:546-546A. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.13.125450

- Cattaneo A., Tamburlini G, Stefanini A, Missoni E, Maciocco G, Tognoni G, et al. The seven sins and seven virtues of universal health coverage. Third World Resurgence. 2015; 296/297:13-5.

- Illich I. Medical nemesis: the expropriation of health. New York: Pantheon; 1976.

- Flessa S. Arme habt ihr allezeit! ein Plädoyer für eine armutsorientierte Diakonie. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht; 2003. German.